What Good is Patriotism? 1 Jul 2017 12:17 PM (7 years ago)

The scene is framed, the shutter is depressed, and the image of lovely Canadian children waving the old Maple Leaf is captured, a timeless statement of tribal affection and loyalty. For many, this photograph will likely stir positive, even emotional feelings for Canada, its history, and what our country seems to represent among the family of nations. But on this Canada Day, it is worth stepping back and taking a picture of the picture and ask ourselves, What good is patriotism?

The scene is framed, the shutter is depressed, and the image of lovely Canadian children waving the old Maple Leaf is captured, a timeless statement of tribal affection and loyalty. For many, this photograph will likely stir positive, even emotional feelings for Canada, its history, and what our country seems to represent among the family of nations. But on this Canada Day, it is worth stepping back and taking a picture of the picture and ask ourselves, What good is patriotism?

Recently I’ve been asking myself that question, as well as reading what philosophers and social scientists have to say. What I have learned is that the concept of patriotism, like other emotions and attitudes, has no clear definition but, rather, sprawls across a wide continuum. At one end, it embodies a healthy pride in a community’s achievements and implies a commitment to work for the good of that community, as was evidenced during the recent floods in many parts of the country. At some point, though, patriotism morphs into an aggressive nationalism that seeks to build up the homeland by cutting down one’s neighbours. At its best, patriotism brings people together while allowing for honesty and dissent. At it worst, it breeds conceit, arrogance, and intolerance.

On this matter, I stand with psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, who once wrote: “Nationalism is our form of incest, is our idolatry, is our insanity. Patriotism is its cult.” Fromm was clearly referring to the dark side of patriotism, not the pure interest in the nation’s spiritual well-being, and he could not countenance its manipulative and corroding power. “Just as love for one individual which includes love for others is not love,” he wrote, “love for one’s country which is not part of one’s love for humanity is not love but idolatrous worship.”

Is there a form of patriotism capable of making us stronger as a country without debasing our moral standing? Psychologist Mark Sandilands studied the dynamics of patriotism during the 1970s—when economic and cultural nationalism were on the rise in Canada. To illustrate the positive power of patriotism, he points to the individual who has strong self-esteem. “Positive self-esteem leads to a healthier and more creative person,” he says. “He doesn’t allow bullies to push him around, but he also accepts other people.” Pride I one’s country, in its broadly shared values and history, and in its vision for what the country can be for others—these are all ingredients in high self-esteem and strong mental health. It is a patriotism with soul. And the measure of such patriotism is better made by observing how people respond to national or regional crisis, for example, than by counting how many medals are won in the Olympics.

Taking another look at the photograph, we can only hope that the flag-waving children enjoying Canada Day festivities will display such quiet confidence in their country when their own time comes to hold the camera.

A version of this piece was published in the June/July 1998 issue of Equinox magazine.

Constraint as Liberation 3 Jun 2017 7:44 AM (7 years ago)

While visiting his family in India, Suchit Ahuja was treated to a master class in frugal innovation. As a PhD student at Smith School of Business, Ahuja was familiar with the concept. Frugal innovation refers to the process of reducing the cost and complexity of a good, stripping down its production, and focusing on its affordability, accessibility, availability, and sustainability.

While visiting his family in India, Suchit Ahuja was treated to a master class in frugal innovation. As a PhD student at Smith School of Business, Ahuja was familiar with the concept. Frugal innovation refers to the process of reducing the cost and complexity of a good, stripping down its production, and focusing on its affordability, accessibility, availability, and sustainability.

Some of the frugal innovations Ahuja saw were on a modest scale: a man operating a food cart, for example, used a car battery to power his tools and food processing equipment. When he returned to collect data for his dissertation, he found more ambitious examples, such as a garbage collection and recycling ecosystem driven by a mobile app. Through the app, volunteers are recruited, trash is segregated, and reports are issued on how much and what type of garbage is collected and where it is being processed.

“All of the people who are responsible for garbage recycling and processing are now finding dignity,” Ahuja told me. “Their entire livelihood has changed and improved radically because this implementation of IT has helped them find a new identity. They’re now seen as valuable members of society, helping recycle and keep the city clean.”

Ahuja was struck by the enabling role of information technology in such resource-constrained environments, marked by the lack of access to basic resources such as electricity or even non-existent infrastructure. “I saw a lot of other implementations of how people were using IT to solve problems that would otherwise be addressed by governments,” he said. “Food, public health, education, taxation, sanitation. It’s all becoming possible because of the access we now have to emerging technologies, mobile phones, and analytics applications. One of the key aspects is, how do you innovate for affordability and sustainability at the same time?”

Back at the Smith School of Business, Ahuja teamed up with his dissertation supervisor Yolande Chan, E. Marie Shantz Professor of IT Management, to develop a model for what they call “frugal IT innovation,” a variation of frugal innovation in which IT takes the leading role. They came to see frugal IT as having three dimensions: business innovation (in business strategy or cost structure), technology innovation (influencing products, processing, agility), and social innovation (driving sustainability or social entrepreneurship).

“The market is demanding that we’re more socially responsible. It’s demanding that the technologies are current and emerging. The market is asking for this new business model and rewarding it”

Firms that practise frugal IT see opportunity in adversity — for them, constraints actually drive innovation. They know how to do more with less, think and act with flexibility, and engage local communities and partners in setting up a grassroots value chain to locally build, deliver, and support their solutions.

Significantly, they are also less likely to be beholden to legacy IT systems and processes, which gives them the freedom to source low-cost IT strategies. Research has shown that they often spend a larger percentage of revenue on digitization than more mature firms and are faster to market with new offerings. They achieve it by leveraging emerging IT technologies and open source platforms: social media, mobile computing, analytics and business intelligence, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things.

Successful practitioners of frugal IT focus more on value creation than on developing intellectual property for later use. Ahuja says companies can bring a lot more intellectual capital on board by creating digital platforms that enable new ideas and products to be generated by customers, vendors, and suppliers in collaboration with the firms.

Frugal IT innovation is not only a paradigm for emerging economies. Many of the constraints and challenges faced by firms that operate in emerging markets are also faced by firms operating in rural areas of developed markets. Challenges such as access to a highly skilled workforce or potential investors, an ecosystem for developing networks, and basic IT infrastructure such as broadband internet connectivity are common.

There are lessons for large firms as well. Some multinationals, such as General Electric, are now designing basic products such as affordable medical devices in developing countries, sometimes with the intention of selling them in developed countries. Renault-Nissan even operates a centre for frugal engineering in India. In some cases, separate sales teams and distribution channels are being built to support these lines.

“The elements of frugal IT innovation are what the market is demanding,” Chan told me. “The market is demanding that we’re more socially responsible. It’s demanding that the technologies are current and emerging. The market is asking for this new business model and rewarding it.”

Quality Matters. So Does Trust 10 May 2017 7:57 AM (7 years ago)

Today, Health Quality Ontario released a report on health system quality that deserves wide circulation. I worked with HQO to help develop and write this report, and the experience had a big impact on me, both as a patient and a student of organizations.

Today, Health Quality Ontario released a report on health system quality that deserves wide circulation. I worked with HQO to help develop and write this report, and the experience had a big impact on me, both as a patient and a student of organizations.

Healthcare is the most complicated environment in which to make system change. That’s because the last mile of change has to pass through many well-rooted professional and administrative cultures that don’t necessarily mesh well with others. The kind of change that’s required in this sector requires continuous learning, not only within groups and teams but across institutions. That’s where culture comes in, and why I believe that trust is the force of nature that holds a quality-first health system — any system for that matter — together.

Here’s what we write in the report about trust:

As the earth shifts beneath the health system, trust – interpersonal and institutional – takes on new meaning. It used to mean simply that doctors were trusted to know the best treatment plan to follow, without questioning about alternatives; that health care institutions were trusted to carry on their business with limited public accountability; and that health care professionals were trusted even though they worked with little collaboration.

Today, the health system operates on very different principles. Patients expect a greater hand in their own treatment plans and in shaping the system; they need to trust that they are being given the right information to make informed decisions. Institutions are adapting to a new world of accountability; they want communities to trust that resources are being used wisely and employees to trust that smart strategic decisions are being made that will lead to quality outcomes. Health care professionals are now expected to work more collaboratively across professions; trust is essential for decision-making to be shared. And system funders need taxpayers to trust that public funds are being used efficiently and wisely.

Trust is a fragile commodity. It is hard to gain and easy to lose, particularly in an age of media reports on system flaws and shortcomings. Perversely, measures to promote transparency and trust – such as releasing ever more system performance data – can also increase the distrust that clinicians and patients feel towards the system itself when they feel the data do not accurately reflect reality.

It can feel like a struggle to trust the system and to protect the trust that others have in you. But for anyone committed to supporting a culture of quality, it is a struggle worth confronting, because without trust, organizational and system learning is severely degraded. In an environment of distrust, providers and managers are loath to admit failure, and without admitting failure, there is limited opportunity for continual improvement.

“We hide our failures in service delivery innovation, even from ourselves,” says Merrick Zwarenstein, director of the Centre for Studies in Family Medicine at Western University, who has written about what is known as high-reliability culture. He has called for a process of “systematically identified failure” in which planned innovations are identified, including goals, criteria for success, and methods of evaluation.

What kind of culture does the health system need so that groups can collaborate with one another with confidence and candour, and learn from clinical missteps and innovations that fall short?

It starts with trust. And trust starts with the willingness to share relevant information, open communication, meaningful culture metrics, and respect for diverse views. From there, building a strong leadership cadre, increasing the capacity to continually improve, enhancing professional cultures, and engaging patients will get Ontario to a health system where quality truly matters.

DOWNLOAD Quality Matters: Realizing Excellent Care for All

Framing Issues on the Fly 9 May 2017 5:33 PM (7 years ago)

Is it climate change or global warming? Does outsourcing to a developing country lead to sweatshops or opportunities for advancement?

Is it climate change or global warming? Does outsourcing to a developing country lead to sweatshops or opportunities for advancement?

Both in the arena of public opinion and the marketplace, firms, political groups, and non-government organizations (NGOs) are perpetually locked in framing and re-framing exercises to try and establish their view of an issue as the dominant one.

Framing happens all the time, but the stakes for firms are particularly high when they have to navigate contentious issues, such as those involving regulatory power, the environment, or a social cause.

It is also a highly fluid process tied to organizational strategy, one that intrigues Smith School of Business researcher Jean-Baptiste Litrico. “I’m really interested in how industries evolve and change towards integrating more socially relevant issues in the way they function,” says Litrico told me during an interview.

Litrico and a fellow researcher from McGill conducted a multi-pronged study on framing focusing on civil aviation. It was a good choice: airports and airlines have been under pressure from NGOs and governments to mitigate their environmental impact, particularly in North America and Europe. In a fairly short period, civil aviation evolved from a praised icon of globalization to a symbol of environmental degradation.

The researchers conducted interviews and other industry fieldwork and did a content analysis of the leading trade journal to track how two key issues — noise and emissions — were framed as they played out.

Between 1996 and 2001, the noise issue placed airports in the crosshairs. Then, between 2007 and 2010, carbon emissions was the dominant issue that forced airlines on their back heels. While the issues were different, the way they were framed by the key actors — airports and airlines — showed a similar pattern.

In the case of noise, airports originally framed the issue as an external disruptor from which the core business activity needed to be buffered. They presented it as a regulatory issue, complaining about restrictive measures imposed by local governments.

Over time, this denial gave way to an openness to substantive change. Airports eventually came to view noise as an operational issue and some proudly announced steps to discourage night traffic and reduce aircraft noise. “In other words, their framing shifted from buffering, or resistance of the issue, to integration, or acceptance and proactive engagement,” Litrico says.

The noise controversy subsided in 2001 when a new noise standard was adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization and stronger noise abatement procedures were put in place.

This buffering-integrating framing dynamic played out in similar fashion with the carbon emissions issue, this time with airlines in the driver’s seat. Airlines early on felt directly targeted by growing public awareness of the carbon impact of flying and by the development of local carbon trading schemes in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. They originally framed the carbon emissions issue as a threat to the sustainable growth of the industry before promising to slash their emissions.

Why did some airports and airlines eventually come to realize that resisting pressures for change was not an effective long-term strategy and thus shifted their framing of the issues? Litrico provides three reasons. The first was that they received negative moral judgments from the public — airline executives, for example, were concerned of being viewed as the next tobacco industry. The second was the looming threat of externally-imposed regulation. And the third was pressure from within the sector itself. Airports in Europe were among the stakeholders pressuring airlines to accept carbon emissions regulation.

Culture certainly plays a part in the framing process. The way issues are framed is coloured by the values and unwritten beliefs of how the world works, Litrico told me. But for many organizations, the buffering-integrating model can be a helpful way to understand why issue life cycles unfold the way they do.

What Really Explains Why We Waste Food? 9 May 2017 11:23 AM (7 years ago)

If you’re a consumer who wants to reduce the amount of food ending up in the dumpster or recycling bin, there are conscious choices you can make: store food properly, reduce portion sizes, stick to a shopping list. But, as I learned from a conversation with consumer behaviour researcher Monica LaBarge, what happens unconsciously can have just as big an impact on how much food is wasted.

If you’re a consumer who wants to reduce the amount of food ending up in the dumpster or recycling bin, there are conscious choices you can make: store food properly, reduce portion sizes, stick to a shopping list. But, as I learned from a conversation with consumer behaviour researcher Monica LaBarge, what happens unconsciously can have just as big an impact on how much food is wasted.

In one recent field study, for example, researchers found that people wasted more food when eating from a disposable plate than from a ceramic plate. It seems we associate “disposable plates” with “waste” and “permanent plates” with “consume.”

To really tackle the food waste problem, says LaBarge, an assistant professor of marketing at Smith School of Business, we need to better understand these sorts of biases that drive consumer behaviour.

While food is wasted from the farmer’s field to the dumpster behind the neighbourhood restaurant, Labarge and a number of her colleagues focus on four links in the chain of food waste. These links — what they term the “squander sequence” — are where consumer decisions are responsible for much of the waste.

At the point of sale or pre-acquisition stage, for example, Western consumers expect unblemished food and perfect packaging. From a psychological viewpoint, it’s perfectly understandable; by instinct, people want to protect themselves from objects that might pose a threat to health or safety.

To address this driver of food waste, LaBarge points to consumer education campaigns in Europe that are teaching consumers that ugly produce is still edible. The French grocery chain Intermarche launched an Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables television and print campaign that was credited with selling 1.2 million tons of “inglorious” fruits and vegetables in its first two days and increasing store traffic by 24 percent.

As well, apps such as Gander provide consumers with spontaneous discounts at participating restaurants that have overstocked or soon-to-be-discarded food.

At the consumer acquisition stage, biases abound. According to the planning fallacy, we underestimate the amount of time it takes to consume all the food in our shopping baskets. Thanks to general optimism bias, we overestimate the useful life of perishable items. Because of present bias, we buy on impulse and overlook long-term outcomes such as the inconvenience of preparing certain foods. Naive diversification bias drives us to place a high value on variety when standing at grocery store shelves and assessing our options.

If we were more aware of these drivers, presumably we’d be in a better position to make more prudent purchases that reduce food waste.

Consumers, for example, can learn to challenge the idea that larger is necessarily better value and to better plan trips to the grocery store. And policy makers can consider higher taxes for certain types of food or formats to cut down on waste.

At the consumption stage, expiration dates are major drivers of food waste. One study cited by LaBarge estimates that 17 percent of household waste in the U.S. is due to food products being past their best-before dates.

Although well meaning, expiration dates can be more confusing than useful. There are no rules or guidelines set by any governing body in Canada regarding when certain food products are no longer at peak quality. There is wide variation in how these labels are applied and misunderstanding among consumers about what they really mean. The labels are not directly related to food safety, yet 50 percent of consumers incorrectly believe that eating foods after their sell-by or use-by dates can put their health at risk.

There are plenty of ideas for how to standardize date labeling but policy makers need to follow through. Researchers can do their part by studying the effectiveness of discounting food that is nearing its best-before date to see if such a tactic can nudge consumers towards new habits.

Meanwhile, policy makers and enterprising techies can educate consumers about expiration dates and what they mean for different products. The Green Egg Shopper app, for example, gives consumers estimates for the useful life of fresh and packaged foods.

At the disposition stage, consumer behaviour can confound conventional wisdom. The phenomenon known as the licensing effect shapes consumer attitudes toward composting. According to this effect, people believe that by acting virtuously in one domain they get a free pass to behave less virtuously in another. According to one survey in 2015, 41 percent of respondents who compost said they were not bothered when food was wasted.

Consumers may also exhibit biases when attributing the causes of food waste. When they eat out at a restaurant or cafeteria, people tend to attribute food waste to the restaurant or cook. The thinking is that since they don’t control the food portion, they’re not guilty of waste. LaBarge and colleagues suggest that researchers should consider whether consumers are, in fact, more likely to waste excess food when portion size is delegated, as well as what factors lead consumers to attribute portion size to others versus themselves.

Any insights that consumer behaviour researchers can offer to help us remove our blinders when it comes to food waste couldn’t come soon enough. The frustrating reality is that roughly 40 percent of food produced yearly in Canada is wasted. In the U.S., one in six people says that food runs out at least once a year; during that same period, a typical four-person household in the U.S. discards $1,500 worth of usable food. That’s the cost of our biases.

When A Magazine Loses Its Way: Larger Lessons from the Canadian Geographic Fiasco 23 Jul 2015 7:50 AM (9 years ago)

Canadian Geographic (CG) magazine and its owner, The Royal Canadian Geographical Society (RCGS), are having a very bad month. First, there were hard questions about the curious role of RCGS Chief Executive Officer, John Geiger, during and after the search for John Franklin’s doomed flagship, HMS Erebus. This week, the crowd-funded news site Canadaland revealed in a series of posts that CG suffered several serious ethical lapses: failing to indicate that a magazine feature was actually paid for by an outside organization, spiking and then rewriting a story in order not to offend a “partner,” allowing the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers to review and shape content for educational material distributed to classrooms across Canada, and breeding a caustic culture for employees.

Canadian Geographic (CG) magazine and its owner, The Royal Canadian Geographical Society (RCGS), are having a very bad month. First, there were hard questions about the curious role of RCGS Chief Executive Officer, John Geiger, during and after the search for John Franklin’s doomed flagship, HMS Erebus. This week, the crowd-funded news site Canadaland revealed in a series of posts that CG suffered several serious ethical lapses: failing to indicate that a magazine feature was actually paid for by an outside organization, spiking and then rewriting a story in order not to offend a “partner,” allowing the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers to review and shape content for educational material distributed to classrooms across Canada, and breeding a caustic culture for employees.

For many Canadians, Canadian Geographic is like a family heirloom. They grew up with the magazine, learned about the country through the magazine’s features and maps, and then took out subscriptions for their kids. The Society itself, under the patronage of the Governor General, has made incalculable contributions to geographic knowledge. The revelations of the past month are not going down easily.

The revelations are not going down easily for me either. I have been writing for the magazine for more then 15 years, and was a senior editor for three years. I saw many of these troubles first-hand, and resigned in December 2012 after the magazine crossed what I considered a “red line.”

It’s clear that these episodes would make a great case study for journalism schools and media studies classes, but my interest here is to draw out lessons that may be of interest for organizations outside of the media bubble.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN BOARD MEMBERS ARE ASLEEP AT THE WHEEL

Almost all the accusations of betrayal are being directed at the magazine’s senior leadership, and that’s understandable. I would argue that these sorry episodes are partly an indictment of the RCGS’s Board of Governors. Ultimately, they are responsible for the welfare of the organization and for how it fulfills its mission. Over the years, I believe some of RCGS governors were made aware of staff concerns about the influence of sponsors on magazine editorial but did nothing. They saw the turnover on the masthead and asked no questions (ironic considering the chair of the board for many years was an experienced journalist and newspaper editor). In governance circles, this is hardly unusual. But often there is a price to be paid down the line: when board members fail to question management assumptions, shy away from fierce conversations, or just mail it in, they signal to management that there will be no accountability. And when there’s no accountability. . .

WHEN YOU’RE A MASTER OF THE UNIVERSE, RISK ASSESSMENT IS FOR LOSERS

With no accountability, hubris takes root like a dandelion. Organizational leaders begin to think they’re invincible and untouchable, and push the envelope with ill-conceived initiatives. They fail to properly assess the risks that may arise from their actions, an underappreciated skill of effective leaders. At CG, the business model is built largely on a foundation of partnerships with government departments and agencies, industry associations, and corporations. CG is not alone among media properties in following this path, yet it is a model requiring a delicate touch. My hunch is that CG leaders got into trouble by operationalizing their sponsored content model too aggressively and with no guiding framework or principles of engagement that aligned with their mission. Whatever had to be done to close a deal, they did. As a result, they lost sight of those whom they ultimately served. Failing to disclose that a magazine feature was actually paid for by a “partner” or letting an industry association shape educational material to suit its interests shows a stunning disregard for foundational principles of operating a magazine or non-profit. CG leaders must have assumed that readers, Society Fellows and members, and teachers wouldn’t find out or care. Did they assess the potential risks in the event their assumptions proved to be wrong? These are the risks they must now confront: a loss in donations to the RCGS; revolt by Society Fellows and members; the cratering of brand equity of the magazine (already diminished over the years), its educational arm, and Society itself; plummeting staff morale; and gun-shy partners no longer wanting to be associated with damaged goods. If CG leaders were to run a risk-benefit analysis today, would they make the same decisions?

FOR SPONSORS, KNOW WHEN ENOUGH IS ENOUGH

CG refers to its sponsors as “partners” yet it is usually not a partnership of equals. Particularly in the case of sponsorships by industry associations, it is easy to identify the senior partner from the junior. In such cases, the sponsor can push for concessions, such as the opportunity to shape storylines or approve content. But expecting a magazine to abandon its editorial independence and ignore its core mission is obnoxious and, I would argue, bad business. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers must be pleased to have the opportunity to get its message out to classrooms across Canada. I suspect they did not fully calculate the all-in price of the CG sponsorship, namely yet another reputational hit. A really savvy sponsor with a long-term view would write a cheque and actually insist on a hands-off approach to controlling content. In my time at CG, I worked with one federal government agency that took this very attitude. They did not want to know what stories we were working on as part of the partnership and had no interest in reviewing content before publication. They didn’t expect us to hide their involvement.

WHEN YOU’RE CAUGHT OUT, TAKE THE OPPORTUNITY TO PRESS THE RE-SET BUTTON

Crisis communications is a tough business. More often than not, it’s a question of mitigating losses, though in rare cases organizations have been able to turn a reputational hit into a positive. Unfortunately, I don’t think Canadian Geographic is doing itself any favours with how it is responding to this week’s revelations. I’m afraid the statement it posted yesterday, which fails to address the damning evidence presented by Canadaland, will make matters worse with the groups most invested in its future. Here is another way RCGS leaders could have responded: “In challenging times for the media, partnerships with respected organizations give us the opportunity to present important stories and educational materials to Canadians. We understand that concerns have now been raised that some of these arrangements may have undermined the editorial integrity of Canadian Geographic and its educational arm. To ensure our most important partners — subscribers, Society Fellows and members, teachers, and Canadians interested in their country — are respected, we will ask an outside consultant to review our editorial processes and recommend changes. Most importantly, within the next month, we will develop a framework that will guide all of our dealings with partners, and post this framework on the RCGS website.” It’s not an ideal response but one that would point a way out of this world of pain.

In the weeks ahead, I look forward to seeing how the Board of Governors and CG leaders react. The board can use this incident to tighten its oversight, better define how to work with partners, and make these decisions transparent. Subscribers, teachers, donors, and Fellows will be watching closely as well.

To Change Corporate Culture, Look to Hidden Influencers 20 Aug 2014 6:22 AM (10 years ago)

In a few months, we will be celebrating the 20th anniversary of one of the more influential management ideas: the change management process advanced by Harvard Business School professor John Kotter (pictured at right). Kotter’s model is the roadmap for how most organizations prepare themselves for new initiatives or adapt to outside shocks.

In a few months, we will be celebrating the 20th anniversary of one of the more influential management ideas: the change management process advanced by Harvard Business School professor John Kotter (pictured at right). Kotter’s model is the roadmap for how most organizations prepare themselves for new initiatives or adapt to outside shocks.

Kotter laid out an eight-step process for how to catalyze the troops and deal with internal resistance:

- Create urgency

- Form a powerful coalition

- Create a vision for change

- Communicate the vision

- Remove obstacles

- Create short-term wins

- Build on the change

- Anchor the changes in corporate culture

There is plenty of logic supporting this process but it’s hardly foolproof. Blame the idea or the implementer but the fact is that change projects have a lousy track record. One of the most recent studies — the Katzenbach Center at Booz & Company surveyed more than 2,200 executives, managers, and employees— showed that only about half of transformation initiatives accomplish and sustain their goals. The usual obstacles: change fatigue, lack of competency to sustain change, and insufficient consultation in selecting and planning a project.

From the study, Booz consultants took away on big conclusion: that when transformation initiatives fall short, it is usually because corporate culture was an afterthought. Among the survey respondents who said the changes at their companies weren’t adopted and sustained over time, they write in Culture’s Role in Enabling Organizational Change, “only 24 percent said their companies used the existing culture as a source of energy and influence during the change effort. Only 35 percent of respondents who said change efforts hadn’t succeeded saw their companies as trying to leverage employees’ pride in, and emotional commitment to, their organizations. By contrast, cultural levers were at least twice as likely to have played a role in change programs that had succeeded.”

The Booz consultants say there is a disconnect between what many organizations say about culture and how much they attend to it. When they roll out a change project using Kotter’s eight-step process, firms seem to zero in on two levers — communications and leadership alignment — to the exclusion of others. “Culture is the last step in Kotter’s formula, something that can be addressed only after new practices have taken hold and proven their value,” the researchers note. “As our data suggests, culture is often not addressed at all. These priorities need to be rethought.”

When company leaders believe they know who the hidden influencers are, they are almost always wrong

It’s not surprising, really, given how culture is embedded in the marrow of an organization. It requires great insight, deft handling, and painful adjustments to make cultural change stick. One effective strategy is to tap informal peer networks. The Booz consultants provide an example of one global technology company that enlisted 2,000 “pride builders” — highly respected managers with leadership qualities “who excel at helping colleagues feel good about their work” — to connect a new initiative to the company’s distinctive culture. Different tactics were used in different regions. “In Asia, the pride builders created a game show to remind employees of the company’s many assets and cultural strengths. In Europe, the pride builders set up a photo contest focusing on the cultural attributes that were most important at the company. The company also held a global contest, in which senior leaders — and eventually all employees — were encouraged to make videos about the company’s culture and how they tried to embody it every day. (The videos were voted on by employees.)”

In large and even medium-sized organizations, how do you identify these social network hubs or “hidden influencers”? They are often people with very low profiles to whom other employees go for advice or who quietly bring together employees from different parts of the firm. Consultants from McKinsey & Company suggest one way to identify these special people is by using “snowball sampling,” a survey technique used by social scientists. Writing in the McKinsey Quarterly, the consultants explain that this technique could be adapted to the corporate world: companies could send out an e-mail survey to employees that ask, “Who do you go to for information when you have trouble at work?” or “Whose advice do you trust and respect?” This is a quick way to create a “snowball effect” and generate a list of hidden influencers.

In their work in a wide range of industries, the McKinsey consultants have found that influencer patterns almost never map onto the organizational chart, and that when company leaders believe they know who the influencers are, they are almost always wrong. “At one large North American retailer,” they write, “we compared a list of influencers that two store managers created before the survey with its actual results. Between them, the managers overlooked almost two-thirds of the influential employees their colleagues named; worse, both managers missed three of the top five influencers in their own stores.”

Is Transparency a Greater Priority for CEOs Than Corporate Communicators? 5 Aug 2014 5:59 AM (10 years ago)

I recall an interview that MIT Sloan Management Review conducted in 2012 with Andrew McAfee of the MIT Center for Digital Business. McAfee was the guru who coined the term Enterprise 2.0 to describe the potential for collaboration tools to improve how organizations work. In discussing CEO attitudes around social networking tools, McAfee had this to say about internal communication flows:

I recall an interview that MIT Sloan Management Review conducted in 2012 with Andrew McAfee of the MIT Center for Digital Business. McAfee was the guru who coined the term Enterprise 2.0 to describe the potential for collaboration tools to improve how organizations work. In discussing CEO attitudes around social networking tools, McAfee had this to say about internal communication flows:

“When I talk to CEOs, they desperately want to hear the voices of their customers, the voices of their employees. They want the straight talk to flow down and flow up in the company. But I also get the impression that there’s kind of a middle layer that has traditionally been the signal processor, both up and down, and some of them don’t want to see that role go away. The middle is very often a conservative place in organizations. The challenge is that the top can be sincerely interested, and there can be a lot of frontline people who are sincerely interested, but it’s what happens in the middle that can determine success and failure.”

The “middle” to which McAfee refers is largely the purview of communications professionals, the signal processors in most organizations. Like HR professionals, comms people often complain of a lack of respect and role confusion. This insecurity may be explained by a lack of alignment around the roles and responsibilities of corporate communications — CEOs and communicators may not be on the same page.

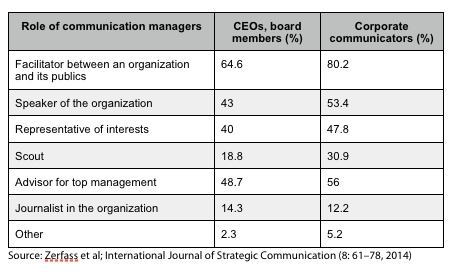

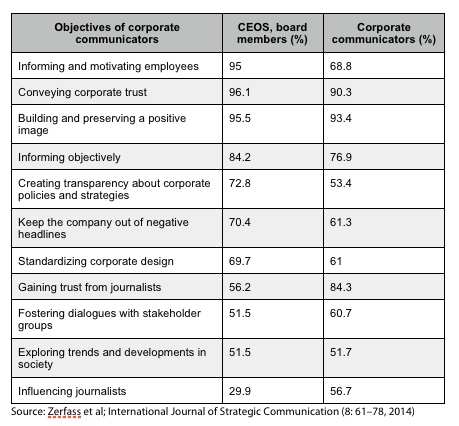

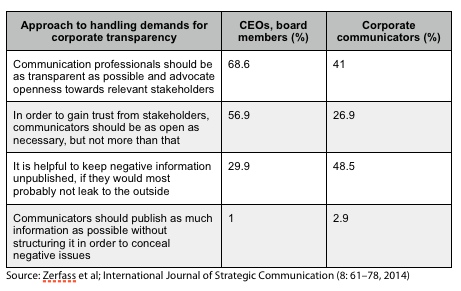

This is the ground that a team of German management researchers explored, and they came away with some thought-provoking conclusions. Researchers Zerfass (U Leipzig, Germany), Schwalbach (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin), Bentele (U Leipzig), and Sherzada (U Leipzig) conducted two surveys of 602 CEOs and executive board members as well as 1,251 communication managers from German companies in 10 industries.

They found top executives and communications professionals agree that communicators act as “facilitators” between the organization and its stakeholders, with moderate influence. And they both believe that a positive image and corporate trust are the most important objectives for corporate communications.

According to the German survey, there are many areas in which CEOs and communications professionals differ.

Role of corporate communicators — Communicators are much more likely than CEOs to see their role as official spokespersons, senior management advisers, and “scouts.”

Objectives of corporate communications — While communications professionals rate trust ascribed by journalists and fostering the corporate image very high, CEOs value motivating employees and transparency much higher. Interesting, CEOs scored “informing objectively” higher than did the communicators.

How to deal with demands for transparency — Here are the biggest differences. CEOs have a much higher expectation that communicators be as transparent as possible and not hide negative information.

The researchers note that while communications professionals often demand a stronger strategic involvement, “as long as their visions do not match those of their superiors, it is quite understandable that CEOs do not see a necessity for an increased strategic influence of communicators.”

The survey was most telling when participants were asked to judge the future importance of corporate communications. Two-thirds of the CEOs and executive board members interviewed predicted an increasing importance of corporate communications in the short-term due to the impact of social media and more active stakeholder groups. By contrast, only 45 percent of communications professionals believed their profession would gain more power within the next three years.

Keep in mind that this survey was done within German organizations, and some of these attitudes may not be shared among North American business leaders and communicators.

Ansgar Zerfass, Joachim Schwalbach, Günter Bentele, and Muschda Sherzada; Corporate Communications from the Top and from the Center: Comparing Experiences and Expectations of CEOs and Communicators; International Journal of Strategic Communication (8: 61–78, 2014)

Misguided Activists: Why Target the Good Guys? 25 Jul 2014 7:12 AM (10 years ago)

On this plane of existence, there are very few saints and an awful lot of sinners; in the corporate world, it’s even more crowded. So if your mission is to name and shame sinful firms, you can pick off your targets blindfolded.

On this plane of existence, there are very few saints and an awful lot of sinners; in the corporate world, it’s even more crowded. So if your mission is to name and shame sinful firms, you can pick off your targets blindfolded.

But activists who want to rally public support against industry practices have to make choices. Strategically, when they embark on a campaign, which companies get the flash mob and which the free pass? Is it the company that has invested in corporate social responsibility (CSR) and has a good reputation or the company with the consistently poor track record?

Brayden King and Mary-Hunter McDonnell (both of Kellogg School of Management) studied this issue and came up with an answer that is both surprising and logical. They collected information on all U.S. boycotts targeting publicly-traded companies that were covered by top national newspapers from 1990 to 2005, and matched each boycotted company up with company-specific financial data and reputation rankings.

They found that firms in the highest reputation category were almost six percent more likely to be targeted than firms that were not listed in the reputation rankings at all. “This evidence suggests that for all of their positive benefits,” they write in a working paper, “attempts to enhance CSR and reputation may have an unintentional negative side effect: they amplify a firm’s attractiveness as an activist target.”

Why should this be so? Shouldn’t firms at least trying to be socially responsible benefit from a halo effect? King and McDonnell say that, on the contrary, such firms are prime targets for activists. “If activists see their goal as not only to coerce firms into dropping bad policies and practices but also to increase general awareness about a social issue, then activists have incentives to go after firms that will maximize the likelihood of garnering attention and outrage. High-status firms with identities grounded in prosocial behaviour should attract more attention for perceived normative violations than firms that are not seen in an equally positive light.”

Firms with a stated commitment to social responsibility are also more vulnerable to employee and shareholder discontent if they are seen to act irresponsibly. That would explain why a company such as Starbucks Coffee, with its stellar CSR credentials, would be a frequent target for activists trying to drum up support for a cause.

Large companies with substantial brand investments and positive reputations were guaranteed to attract social movement pressure

This phenomenon showed up in another study, recently published in the American Sociological Review, that examined the anti-sweatshop campaigns of the 1990s. Media-savvy organizations such as the National Labor Committee effectively shamed a handful of apparel companies, notably Nike and The Gap, while other equally guilty companies such as Abercrombie and Fitch and Haggar got off easy.

Tim Bartley (Ohio State U) and Curtis Child (Brigham Young U) built a comprehensive database of anti-sweatshop campaigns in the apparel, textile, and footwear industries from 1993 to 2000 and matched it with 151 U.S.-based firms in these industries. Almost 27 percent of the firms in their sample were implicated in anti-sweatshop campaigns at some point.

They found that large companies with substantial brand investments and positive reputations were guaranteed to attract social movement pressure. “Once companies became targets, they were likely to continue to be scrutinized, even as others (including some aggressive globalizers) flew under the radar.”

So the message to companies that are engaging in community outreach, investing in philanthropy, and rolling out CSR initiatives is that they are only exposing themselves to the threat of future activist targeting.

Meanwhile, firms with consistently poor reputations in this regard, who think that CSR is for sissies, have fewer incentives to clean up their act, knowing that activists will give the unrepentant bad boys a pass.

Is that what activist organizations really want?

Brayden G. King and Mary-Hunter McDonnell, Good Firms, Good Targets: The Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility, Reputation, and Activist Targeting; Available for download here

Tim Bartley and Curtis Child, Shaming the Corporation: The Social Production of Targets and the Anti-Sweatshop Movement; American Sociological Review (August 2014 79: 653-679)

Canadian Activists and Social Media: Not Quite a Love Affair 10 Jul 2014 11:13 AM (10 years ago)

You might think that advocacy groups would be the most enthusiastic adopters of social media. After all, social technologies are tailor-made for relationship-driven groups; they harness loyalty and amplify messages. They help smaller organizations do a lot more than their organizational resources would normally allow.

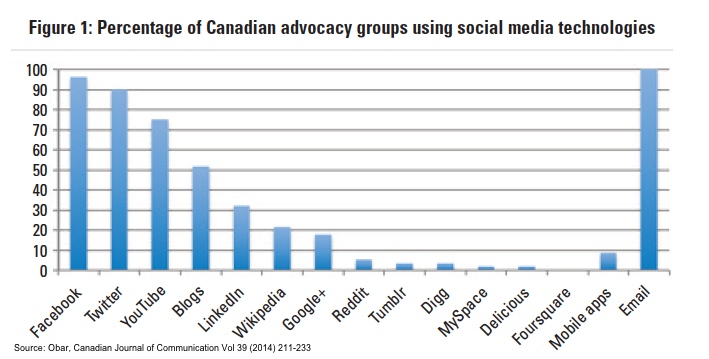

But surveys from a number of years ago suggested that Canadian-based NGOs were slow to enter the world of Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and the like. And today? These organizations, according to Jonathan A. Obar (U Toronto/Michigan State U), have largely made the leap, yet they are still hobbled by a number of hurdles.

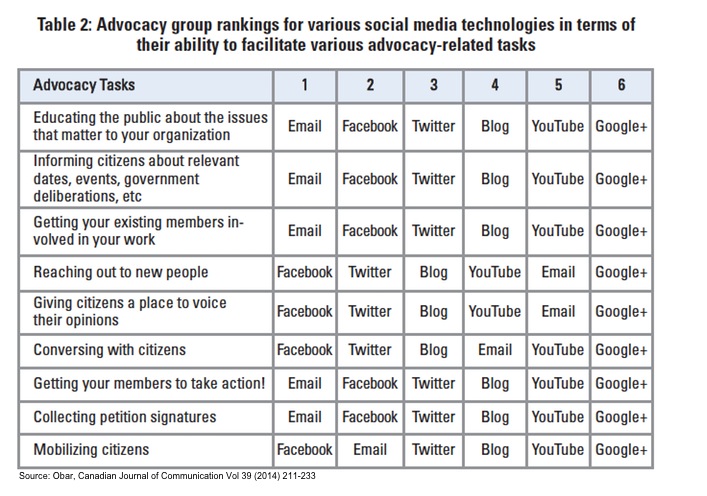

Obar surveyed more than 50 advocacy groups operating in Canada to learn more about how they use social media to further their causes. Some highlights:

- Fifty-four of 56 groups use social media to interact with the public (the outliers: the Fur Institute of Canada and the Louis Even Institute for Social Justice).

- Most groups use Facebook (54 of 56) and Twitter (50 of 56). YouTube is also popular (75%) as are blogs (52%).

- Fifty-two percent use Facebook every day; 30 percent use it a few times a week. Fifty-seven percent use Twitter every day and an additional 22 percent tweet a few times a week. Of the remaining technologies, blogs are used most often, with five of 56 groups blogging every day and an additional 11 blogging a few times a week. Most groups use YouTube a few times a month.

- All 56 organizations send emails to the general public (Feminist Majority Foundation sends emails to 170,000 individuals a few times a week). The majority of groups send emails a few times a week or less, with only three of 56 sending emails once a day or more.

- Email and Facebook were the preferred methods of communication for most tasks. Regardless of Facebook’s ranking, Twitter almost always followed, and blogs were usually the next most popular. Google+ ranked last in all categories.

In his interviews with NGO leaders, Obar found that advocacy groups still see some drawbacks in using social media. For one thing, Facebook, Twitter, and their ilk require a considerable commitment of staff time and resources, and there is a steep learning curve in using social media properly.

Some groups told Obar that they remain unconvinced that social media are effective tools for advocacy. One anonymous NGO manager claimed social media provide “basic recognition, nothing more. A ‘like’ button does not help us in any way.” Another noted, “Social media allows us to create a base movement, but [it] has also created a substantial class of ‘slacktivists’ who … can never truly be nurtured into real activists.” Obar says some groups believe social media may create a false sense of a movement’s reach and influence.

“Qualitative results addressing perceived social media affordances suggest that while groups are enthusiastic about social media’s potential to strengthen outreach efforts, enable engaging feedback loops, and increase the speed of communication, they remain cautious of unproven techniques that may divert resources from strategies known to work,” he wrote in the Canadian Journal of Communication.

It’s worth noting that Canadian activists appear to be laggards in this area. Obar was part of a team that conducted a similar survey in 2012 of 53 advocacy groups in the U.S. All the U.S. advocacy groups surveyed use social media technologies to communicate almost every day.

Jonathan A. Obar, Canadian Advocacy 2.0: An Analysis of Social Media Adoption and Perceived Affordances by Advocacy Groups Looking to Advance Activism in Canada, Canadian Journal of Communication (vol. 39 (2014) 211-233)