Bringing the guilty part to justice: How Facebook, the scouts and one frustrated sister drove youth mobilization in Israel 13 Apr 2011 11:54 PM (14 years ago)

Neta Kligler-Vilenchik

Our work in the Civic Paths team touches on different ways in which participatory culture is linked to realms of civic engagement, particularly for young people. The following story, which has occupied the Israeli media last month, is an intriguing case study both for some questions our team has previously examined (what is the power of storytelling in mobilization?) and aspects we havenâ€ t previously interrogated  (how can “traditional†youth movements fit in “new†efforts of mobilization?).

t previously interrogated  (how can “traditional†youth movements fit in “new†efforts of mobilization?).

The letter on Facebook

“Iâ€ m looking for the right words to describe my pain right now, and just canâ€

m looking for the right words to describe my pain right now, and just canâ€ t find them. Nothing is sufficient to describe the anger I feel, the disappointment, the insult and this sadness.

t find them. Nothing is sufficient to describe the anger I feel, the disappointment, the insult and this sadness.

My name is Yael Grinspan, I am the sister of Shahar, who is today 13, who was hurt in a car accident a year and three months ago. A car accident is the term for what has happened to her, but a part of me refuses to use that term. On Saturday, November 28th 2009, at 4 pm, Mark Patrick drove home while drunk, and drove over a traffic island on which my sister was standing, waiting for the red light to turn green.â€

With these words begun a compelling letter, written by 18 year old Yael Grinspan, sent through Facebook to Yaelâ€ s network of friends and family, under the heading “Bringing the guilty part to justiceâ€. The letter was written in response to the verdict of the drunk driverâ€

s network of friends and family, under the heading “Bringing the guilty part to justiceâ€. The letter was written in response to the verdict of the drunk driverâ€ s trial, which Yael and her family had received that day. The driver, who left Yaelâ€

s trial, which Yael and her family had received that day. The driver, who left Yaelâ€ s sister Shahar paralyzed, unable to speak or move, was sentenced to 600 hours of community service and a 1000 NIS (about $250) fine. Appalled, Yael wrote in her letter:

s sister Shahar paralyzed, unable to speak or move, was sentenced to 600 hours of community service and a 1000 NIS (about $250) fine. Appalled, Yael wrote in her letter:

“A driver caught talking on a cell phone while driving is fined NIS 1,000. A person who threw a shoe at a judge received a three-year prison sentence. The person who took my sister’s life, who destroyed an entire family, will continue to live as though nothing happened.”

In her letter, Yael explained that her family tried to contact the State Prosecutorâ€ s Office, and were dismissed. She finished her letter with the request to share the letters with others, as well as to try and get it to be published in the mainstream media. Later, an online petition was added to the mix.

s Office, and were dismissed. She finished her letter with the request to share the letters with others, as well as to try and get it to be published in the mainstream media. Later, an online petition was added to the mix.

While it is now hard to trace the spread of the letter through the social network that day, its result is clear. Before Yaelâ€ s letter, the story had received limited coverage in news outlets, and close to no public attention. The very morning after Yael had published her Facebook letter, Maâ€

s letter, the story had received limited coverage in news outlets, and close to no public attention. The very morning after Yael had published her Facebook letter, Maâ€ ariv, one of the top mainstream newspapers in Israel, dedicated its cover page to the story, publishing the full letter, as well as a picture of the two sisters.

ariv, one of the top mainstream newspapers in Israel, dedicated its cover page to the story, publishing the full letter, as well as a picture of the two sisters.

Mass media and public response

That day, the story had stirred the state. It went through all the mainstream media channels, including mainstream Israeli newspapers, television appearances, and English language media. In addition, motivated either through the online dissemination of the letter, or through mainstream media, thousands signed the online petition or pressed ‘likeâ€ on the facebook page of the original letter (by now, April 12 2011, the online petition has garnered 76,111 signatures and the facebook page was liked by 60,267, quite amazing for a country of 7 million residents). Reacting to the public attention, the State Prosecutor had contacted the family, promising to personally investigate the case (though in the past days the family had been notified that the verdict cannot be appealed or overturned). By that point, however, Yael Grinspan had received so much public response to her story, that she felt a larger cause needs to be fought.

on the facebook page of the original letter (by now, April 12 2011, the online petition has garnered 76,111 signatures and the facebook page was liked by 60,267, quite amazing for a country of 7 million residents). Reacting to the public attention, the State Prosecutor had contacted the family, promising to personally investigate the case (though in the past days the family had been notified that the verdict cannot be appealed or overturned). By that point, however, Yael Grinspan had received so much public response to her story, that she felt a larger cause needs to be fought.

The Grinspan case had touched on several hot social issues. One was the issue of drunk driving and its ramifications. Drunk driving is a social issue that exists on the Israeli public agenda, but is often framed around youth drinking and driving (more so, perhaps, than seeing youth as its victims). A second social issue that emerged, and the more controversial one, revolved around the inadequacies of the Israeli legal system. Yaelâ€ s letter critiqued the legal system for giving the perpetrator a light punishment, just in order to enable a quick procedure and end a trial. Her claims touched on a loaded social critique of the legal system, which had been blamed for inefficiency, long waits for trials, and procedural problems.

s letter critiqued the legal system for giving the perpetrator a light punishment, just in order to enable a quick procedure and end a trial. Her claims touched on a loaded social critique of the legal system, which had been blamed for inefficiency, long waits for trials, and procedural problems.

The mass media embraced the legal critique aspect of the story, asking Yael what punishment she would have found just, or whether she encountered other people with similar stories of public injustice. The second aspect of the story – drunk driving and its ramifications – was embraced by a somewhat surprising social agent – the Israeli scouts (Tzofim). To understand the nature of the scoutsâ€ involvement, some context is needed.

involvement, some context is needed.

Mobilizing through traditional youth movements – the Israeli scouts

Founded in 1919, the Israeli scouts were the first Zionist youth movement in Israel. It is a nationally based organization, with local “tribes†in different cities and towns, in which most activities are run by youth instructors (aged 16-18), who lead groups of younger kids (from about age 10). One of its most interesting characteristics is that over the last 10 years, its membership has grown by over 55%, while almost all other youth movements in Israel are seeing continuously decreasing membership.

The Israeli scouts define themselves as a political, but non-partisan, youth movement. Thus, while hiking and outdoors activities are part of the repertoire (for both girls and boys, who usually attend mixed gender activities), the scouts see part of their mission as educating youth on burning social issues, while promoting values of democracy, communality, initiative and leadership.

The Israeli scoutsâ€ interest in the Grinspan case began through a personal connection – Shahar Grinspan was, until her accident, a member of the scouts. Yael Grinspan is a youth leader in her local scouts tribe. This association prompted the Israeli scouts to take up the Grinspan case as part of a larger cause, opposing drunk driving and demanding stricter punishments for drunk drivers. Young members of the Israeli scouts all over the nation went out to the public, collecting signatures for Grinspanâ€

interest in the Grinspan case began through a personal connection – Shahar Grinspan was, until her accident, a member of the scouts. Yael Grinspan is a youth leader in her local scouts tribe. This association prompted the Israeli scouts to take up the Grinspan case as part of a larger cause, opposing drunk driving and demanding stricter punishments for drunk drivers. Young members of the Israeli scouts all over the nation went out to the public, collecting signatures for Grinspanâ€ s petition and raising awareness for the issue. Yael Grinspan was soon dubbed a social leader when she headed, in partnership with the scouts, a public protest that was held outside the Israeli parliament on March 22, 2011 (which turned out not as large as hoped – about 2000 people attended, mostly young scout members).

s petition and raising awareness for the issue. Yael Grinspan was soon dubbed a social leader when she headed, in partnership with the scouts, a public protest that was held outside the Israeli parliament on March 22, 2011 (which turned out not as large as hoped – about 2000 people attended, mostly young scout members).

Still, Yaelâ€ s protest was not futile. A parliament member proposed a law, demanding that any plea bargain with perpetrating drivers can only be approved after hearing the response of the victim or their family. In addition, similar cases gained attention, such as the story of Shiri Crassenti, whose 14 year old sister Liza had been hit in a car accident. Shiri demanded justice to the perpetrator, who had regained his driverâ€

s protest was not futile. A parliament member proposed a law, demanding that any plea bargain with perpetrating drivers can only be approved after hearing the response of the victim or their family. In addition, similar cases gained attention, such as the story of Shiri Crassenti, whose 14 year old sister Liza had been hit in a car accident. Shiri demanded justice to the perpetrator, who had regained his driverâ€ s license, even before the trail against him had begun. In response to the attention of the Grinspan case, Shiri had also published a letter on Facebook, and the two were quickly framed by the media as “two sisters in a joint battleâ€.

s license, even before the trail against him had begun. In response to the attention of the Grinspan case, Shiri had also published a letter on Facebook, and the two were quickly framed by the media as “two sisters in a joint battleâ€.

The Grinspan case as Transmedia storytelling mobilization

Following the immense attention the Grinspan case had received in Israel, communication scholars in Israel discussed the story as a case of the power of social networks. Uzi Benziman discussed the way that computer mediated communication creates a sense of intimacy, by giving the sense of a personally targeted communication. Other critics raised the question whether the story of a different person, one who isnâ€ t a photogenic, charismatic young Ashkenazi (of European decent) woman of mainstream Israel, would have achieved the same media attention.

t a photogenic, charismatic young Ashkenazi (of European decent) woman of mainstream Israel, would have achieved the same media attention.

I would like to take a different focus, one that looks at the Grinspan case as one of mobilization, particularly youth mobilization. Here, the question is, what about the Grinspan case enabled the mobilization of youth to massively sign an online petition, go out and collect strangersâ€ signatures, and (for at least 2000 youth) attend a public protest in the capital?

signatures, and (for at least 2000 youth) attend a public protest in the capital?

A key strength of the Grinspan case was the power of the story, as told by Yael. Yaelâ€ s letter, which is simultaneously eloquent and blunt, touched readersâ€

s letter, which is simultaneously eloquent and blunt, touched readersâ€ cords with the personal, intimate story it shared. The story was told from the point of view of an 18 year old girl who witnessed her 13 year old sisterâ€

cords with the personal, intimate story it shared. The story was told from the point of view of an 18 year old girl who witnessed her 13 year old sisterâ€ s life being destroyed. Its power was not only in content but in context: it was part of Yaelâ€

s life being destroyed. Its power was not only in content but in context: it was part of Yaelâ€ s Facebook page, where the profile picture depicts the two sisters (before the tragic accident) on a ski trip. Young readers who navigated to Yaelâ€

s Facebook page, where the profile picture depicts the two sisters (before the tragic accident) on a ski trip. Young readers who navigated to Yaelâ€ s facebook page (which is set to partial privacy to non-friends) could see a personal side of her – in addition to her profile picture, one can see the list of her 412 friends, the name of her high-school, and even “Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry†listed as her college. In her letter, as well as in her subsequent media appearances, Yael maintained an open, honest image, confessing about her relationship with her sister before the accident: “We were simply terrible sisters. We couldnâ€

s facebook page (which is set to partial privacy to non-friends) could see a personal side of her – in addition to her profile picture, one can see the list of her 412 friends, the name of her high-school, and even “Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry†listed as her college. In her letter, as well as in her subsequent media appearances, Yael maintained an open, honest image, confessing about her relationship with her sister before the accident: “We were simply terrible sisters. We couldnâ€ t have one conversation without screaming at each other.†Such statements made Yaelâ€

t have one conversation without screaming at each other.†Such statements made Yaelâ€ s story not only deeply personal, but also particularly resonant for young people.

s story not only deeply personal, but also particularly resonant for young people.

In our work in Civic Paths, we have considered how groups attempting to encourage youth civic engagement use storytelling as an element of mobilization. For the Harry Potter Alliance, an activist group using connections to the magical world of Harry Potter to encourage civic engagement, a fictional story world is used as an impetus to drive youth action. Characters, themes and events from the book, which carry significant meanings for Harry Potter audiences and fans, are paralleled to real world issues, thus creating ground for fan activism. Invisible Children, an activist group focused around awareness-building and fundraising for the ending of the civil war in Uganda and the countryâ€ s redevelopment, uses the power of movies and other media as a tool to tell stories about Ugandan residents, most notably child soldiers and the phenomenon of night commuters. In speaking to members of both these groups, we have found that their sense of identification with the organizations and mobilization to action is largely connected to a shared media experience with stories or content worlds. These media experiences are ones that are powerful on the individual level, and are particularly amplified when they are shared with others, and used as a vocabulary and a motivation for social action. Moreover, the stories these organizations build on are often disseminated as transmedia experiences, using a variety of platforms, while engaging the particular strengths of each platform. Our team member Lana Swartz thus referred to these organizationsâ€

s redevelopment, uses the power of movies and other media as a tool to tell stories about Ugandan residents, most notably child soldiers and the phenomenon of night commuters. In speaking to members of both these groups, we have found that their sense of identification with the organizations and mobilization to action is largely connected to a shared media experience with stories or content worlds. These media experiences are ones that are powerful on the individual level, and are particularly amplified when they are shared with others, and used as a vocabulary and a motivation for social action. Moreover, the stories these organizations build on are often disseminated as transmedia experiences, using a variety of platforms, while engaging the particular strengths of each platform. Our team member Lana Swartz thus referred to these organizationsâ€ efforts as transmedia storytelling mobilization.

efforts as transmedia storytelling mobilization.

The story of Yael Grinspan was likely a powerful narrative, particularly, though not at all exclusively, to young audiences. It was moreover a transmedia story, circulated through a variety of channels, in ways that often tapped the strength of each channel. Commentaries which frame the story only as a manifestation of the power of social networks may thus simplify the picture. Yaelâ€ s story, instead, benefited from the intimacy of a personal letter, transmitted through her own personal social networks; the power of social agents in deciding to spread a message to their networks; the affordances of the Internet which enable a mass signing of a petition, where people simultaneously see their own signatures amassing with those of countless others; the power of mass media in incorporating a story from the social network, and foregrounding it in its front pages. In contrast to pre-planned transmedia stories utilized by activist organizations, Yaelâ€

s story, instead, benefited from the intimacy of a personal letter, transmitted through her own personal social networks; the power of social agents in deciding to spread a message to their networks; the affordances of the Internet which enable a mass signing of a petition, where people simultaneously see their own signatures amassing with those of countless others; the power of mass media in incorporating a story from the social network, and foregrounding it in its front pages. In contrast to pre-planned transmedia stories utilized by activist organizations, Yaelâ€ s story was not planned as a strategic process of transmedia storytelling mobilization. Still, its adoption and adaption to multiple platforms enabled maintaining a powerful coherent story, while also benefiting from the specific affordances of multiple channels.

s story was not planned as a strategic process of transmedia storytelling mobilization. Still, its adoption and adaption to multiple platforms enabled maintaining a powerful coherent story, while also benefiting from the specific affordances of multiple channels.

Role of traditional youth movements

A second interesting point of connection of the Grinspan case to some of the Civic Paths work is the role of the Israeli scouts in the mobilization efforts around the case. As previously mentioned, due to Yael and Shaharâ€ s membership in the scouts, the youth movement rallied around the case to organize a protest against light punishments to drunk drivers. Members of the youth movement not only participated in the protest in front of the Israeli parliament, but also helped collect signatures and raise awareness for the issue. The mobilization cannot be described as a univocally successful one – only 2000 young people arrived at the protest, and a month later, the protest has not been sustained. Still, the connections between Yaelâ€

s membership in the scouts, the youth movement rallied around the case to organize a protest against light punishments to drunk drivers. Members of the youth movement not only participated in the protest in front of the Israeli parliament, but also helped collect signatures and raise awareness for the issue. The mobilization cannot be described as a univocally successful one – only 2000 young people arrived at the protest, and a month later, the protest has not been sustained. Still, the connections between Yaelâ€ s Facebook letter and the scouts is one worth looking into.

s Facebook letter and the scouts is one worth looking into.

Sticker prepared by the scouts for the protest, labeled: "We demand deterrent punishments for drunk drivers!", as well as "letting Shahar's voice speak". On the left is the logo of the Israeli scouts.

One of the questions we ask in our research is, why young people may prefer to become involved through “new†forms of civic engagement, ones that, among other things, make rich use of popular and participatory culture. In our research, participants of IC and HPA shared with us their perception of most traditional non-profits as outdated or not geared toward young people. The Israeli scouts may, for some young people, be similarly seen as an outdated movement, and it is struggling with the image of being irrelevant to the lives of youth today. Partnering with Yael Grinspan on the mobilization around her sisterâ€ s case may thus have benefited both sides.

s case may thus have benefited both sides.

For the scouts, working with Grinspan enabled a public spotlight, spilling some of the media attention around the Grinspan case to the youth movement, which normally is rarely deemed newsworthy. Media coverage of Yael in her scouts uniform, talking to fellow scouts about her sisterâ€ s car accident, or young children in scouts uniform collecting signatures in the mall, were a rare public representation of a movement that prides itself in encouraging youth engagement, but is rarely given a voice in the media. For Yael Grinspan and her family, partnering with the scouts enabled a reliance on an existing movement that has a strong membership base, communication channels with young people all over the nation, as well as a large staff, experienced in public relations and production of protests and public events. These local, on the ground efforts of a public protest complemented the massive signing of the online petition, thus moving the action around the Grinspan case from the often dismissed realm of “online activism†only, to a public protest – a genre of activism traditionally valued in democracy.

s car accident, or young children in scouts uniform collecting signatures in the mall, were a rare public representation of a movement that prides itself in encouraging youth engagement, but is rarely given a voice in the media. For Yael Grinspan and her family, partnering with the scouts enabled a reliance on an existing movement that has a strong membership base, communication channels with young people all over the nation, as well as a large staff, experienced in public relations and production of protests and public events. These local, on the ground efforts of a public protest complemented the massive signing of the online petition, thus moving the action around the Grinspan case from the often dismissed realm of “online activism†only, to a public protest – a genre of activism traditionally valued in democracy.

While Yael Grinspanâ€ s protest had not achieved the goal of upturning the verdict of the drunk driver who hit her sister, it has – at least temporarily – became an impetus for discussion and action for many young people. Perhaps Yaelâ€

s protest had not achieved the goal of upturning the verdict of the drunk driver who hit her sister, it has – at least temporarily – became an impetus for discussion and action for many young people. Perhaps Yaelâ€ s short but intensive experience as a “social leader†may empower her not only to continue fighting her familyâ€

s short but intensive experience as a “social leader†may empower her not only to continue fighting her familyâ€ s cause, but to harness her charisma and rhetoric strength to additional mobilization of young people.

s cause, but to harness her charisma and rhetoric strength to additional mobilization of young people.

A ‘Big Bang’ – and Participatory Fans are now on your TV Screens 30 Mar 2011 9:37 AM (14 years ago)

It’s been a while now since geeks have made the sudden and rapid evolution from social outcasts to trendsetters. Theyâ€ re amongst the coolest people out there at the moment, causing sales of large, geek-style glasses to increase and kids to explore their ‘nerdyâ€

re amongst the coolest people out there at the moment, causing sales of large, geek-style glasses to increase and kids to explore their ‘nerdyâ€ sides in hopes of being the next Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates.

sides in hopes of being the next Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates.

But itâ€ s not just geeks that have all of a sudden become it. Engaged fans have become cool, too. Fan participation has become cool. What used to be seen as the behavior of a confused* minority group that may or may not have lost touch with reality* – this same behavior all of a sudden has become hip.

s not just geeks that have all of a sudden become it. Engaged fans have become cool, too. Fan participation has become cool. What used to be seen as the behavior of a confused* minority group that may or may not have lost touch with reality* – this same behavior all of a sudden has become hip.

Donâ€ t believe me? Consider this:

t believe me? Consider this:

1. Three out of five protagonists of How I Met Your Mother are seen at a Star Wars convention at least once – in addition to countless die-hard Star Wars references between Ted, Marshall, and Barney (to the extent that they consider ANY woman unsuitable to marry Ted if she doesnâ€ t love Star Wars as much as he does, and Barney gets into countless fights with Robin and Lily over the life-sized Stormtrooper he has in his living room).

t love Star Wars as much as he does, and Barney gets into countless fights with Robin and Lily over the life-sized Stormtrooper he has in his living room).

Lily (Darth Vader), Ted (Luke Skywalker), and Marshall (Chewbacca) from 'How I Met Your Mother' at a Star Wars Con

2. Similarly, The Big Bang Theory is full of references to Star Trek and Star Wars, as well as to various comics such as the Marvel series (their collectorâ€ s editions are all over the walls in Sheldonâ€

s editions are all over the walls in Sheldonâ€ s bedroom, for example), and the show includes scenes at fan conventions or the entire gang dressing up in matching fan outfits.

s bedroom, for example), and the show includes scenes at fan conventions or the entire gang dressing up in matching fan outfits.

Rajesh, Leonard, Howard, and Sheldon from 'The Big Bang Theory' all inadvertently dress up the same on Halloween as Flash (from one of their favorite comic series)

3. And even the cases of Harry Potter and Twilight, where both book signings and film premieres consistently prompt thousands of fans to show up in full-on costumes, often camping outside venues several nights before the events to get the best spot in the queue or in front of the stage. And rather than being ridiculed, the news media join into the craze, counting down the hours until a new release with the fans and joining into the debate of whether Harry Potter is a craze or a classic.

Whatâ€ s important here is not the fact that all of these fans exist on television, but the way they are being portrayed in the media. Yes, devoted fans have always existed, and so have fan crazes like the ones surrounding Twilight and Harry Potter. Whatâ€

s important here is not the fact that all of these fans exist on television, but the way they are being portrayed in the media. Yes, devoted fans have always existed, and so have fan crazes like the ones surrounding Twilight and Harry Potter. Whatâ€ s new, however, is that devoted fans are no longer framed as a crazed minority, some weirdoes who are trying to escape from reality. They are portrayed as cool, sometimes funny, but increasingly normal. But where does all of this come from? How did participatory fans all of a sudden make it into some of the most successful TV shows?

s new, however, is that devoted fans are no longer framed as a crazed minority, some weirdoes who are trying to escape from reality. They are portrayed as cool, sometimes funny, but increasingly normal. But where does all of this come from? How did participatory fans all of a sudden make it into some of the most successful TV shows?

One reason could be that TV producers have discovered the continuous source of revenue participatory fans can provide. Unlike ‘everydayâ€ fans that only follow a film or television series for some time before turning to something else, engaged fans stay with their chosen show(s) and film(s) over years, if not decades and even their life. Maybe studio bosses and producers have come to realize that this devotion means additional income from media content that is long past its original airing and its zenith, and so they may now try to engage participatory fandom by showing it on-screen in the first place and in a positive manner at that.

fans that only follow a film or television series for some time before turning to something else, engaged fans stay with their chosen show(s) and film(s) over years, if not decades and even their life. Maybe studio bosses and producers have come to realize that this devotion means additional income from media content that is long past its original airing and its zenith, and so they may now try to engage participatory fandom by showing it on-screen in the first place and in a positive manner at that.

Or maybe itâ€ s all for fun and ridicule. Both How I Met Your Mother and The Big Bang Theory feature relatively geeky main characters, and their devotion to fandoms like Star Trek, Star Wars, and Marvel Comics is often the cause for humor and comedy. However, the positive and amiable depiction of these charactersâ€

s all for fun and ridicule. Both How I Met Your Mother and The Big Bang Theory feature relatively geeky main characters, and their devotion to fandoms like Star Trek, Star Wars, and Marvel Comics is often the cause for humor and comedy. However, the positive and amiable depiction of these charactersâ€ fan dedication suggests otherwise. Fan references and fan commitments may be comedic at times, but they always also highlight the importance of a fandom in a charactersâ€

fan dedication suggests otherwise. Fan references and fan commitments may be comedic at times, but they always also highlight the importance of a fandom in a charactersâ€ life, and whatâ€

life, and whatâ€ s more, the way his/her fandom bonds a protagonist to his/her friends and significant others.

s more, the way his/her fandom bonds a protagonist to his/her friends and significant others.

Which leads me to my third possible reason: Maybe the general public has begun to accept and respect participatory fans. Maybe they have seen engaged fansâ€ continued and lasting commitment to their fandoms, have realized that they are not just following some form of extreme craze, and that they actually (surprise, surprise!) get a lot more out of their fan objects than mere escapism. And maybe they started to think that in a time where we are trying to let anyone live in a way that makes them happy, regardless of social backgrounds, sexual orientation, and religious affiliation, for example, participatory fans could be allowed just the same – without being derided or made fun of, but with being accepted and respected.

continued and lasting commitment to their fandoms, have realized that they are not just following some form of extreme craze, and that they actually (surprise, surprise!) get a lot more out of their fan objects than mere escapism. And maybe they started to think that in a time where we are trying to let anyone live in a way that makes them happy, regardless of social backgrounds, sexual orientation, and religious affiliation, for example, participatory fans could be allowed just the same – without being derided or made fun of, but with being accepted and respected.

As a hopeless optimist and idealist, Iâ€ d like to think that it is mainly reason three – increased general tolerance and respect. If this is not the case, then Iâ€

d like to think that it is mainly reason three – increased general tolerance and respect. If this is not the case, then Iâ€ m still ok with any of the other reasons, as long as participatory fans continue to get their screen time, and do so in a good light.

m still ok with any of the other reasons, as long as participatory fans continue to get their screen time, and do so in a good light.

*Iâ€ m not exaggerating here. These words actually came up in conversations with countless non-participatory fans throughout the last ten years of my life.

m not exaggerating here. These words actually came up in conversations with countless non-participatory fans throughout the last ten years of my life.

Making the Case for Fan Fiction 2 Mar 2011 10:25 PM (14 years ago)

At dinner last night with my screenwriter friend, I got into a discussion of the value of fan fiction, prompted by a comment I had made that indicated that I was fan of the Showtime show, The L Word, and that I read The L Word fan fiction. My friend stated that she could not fathom someone being so obsessed with a TV show as to take the characters and expand on their world and explore their lives.

“These people who are spending so much time and energy on fictitious characters and situations should spend that time and energy cultivating their real life relationships. Only people who are dissatisfied with their lives would spend that much on fan fiction, and reading about people who arenâ€ t even real,†she argued. She was making the argument that people who read fan fiction are “nerds,†which I donâ€

t even real,†she argued. She was making the argument that people who read fan fiction are “nerds,†which I donâ€ t completely disagree with. However, she was discounting the very real emotional attachment that people have to the characters and their stories, which also discounts the values of having a space in which narratives and storytelling are explored around common interests in order to form a participatory community.

t completely disagree with. However, she was discounting the very real emotional attachment that people have to the characters and their stories, which also discounts the values of having a space in which narratives and storytelling are explored around common interests in order to form a participatory community.

So I replied, “But you, who are a screenwriter, should know better than anyone the process of getting into a fictitious characterâ€ s head in order to explore issues and stories through an emotional narrative plot line.†I was flabbergasted that she could not see how people would get emotionally attached to fictitious characters and would want to treat them like real people when, through the process of writing a screenplay, a screenwriter treats these characters like real people in order to portray them and make them feel as real as possible.

s head in order to explore issues and stories through an emotional narrative plot line.†I was flabbergasted that she could not see how people would get emotionally attached to fictitious characters and would want to treat them like real people when, through the process of writing a screenplay, a screenwriter treats these characters like real people in order to portray them and make them feel as real as possible.

“Filmmaking is a business. People spend years and years on films so they can get paid. People spend tons of time writing fan fiction, but never get paid!†She did have a point, a broader topic, perhaps, of how art and creativity has become commodified, standardized with rules of conventions for what will sell. Her argument also touches upon ideas of gift economy and digital labor. Indeed, The L Word Fan Fiction site is completely free. People give freely of their own time to write stories, and others give of their time to comment and give feedback. I countered my friendâ€ s argument, “What, then, do you think of people who make webisodes and short films on YouTube? The value in fan fiction seems to lie in the formation of community. The value of these communities lie perhaps not in economic capital. The Internet has enabled a platform on which people from geographically disparate areas can gather and form a community based on a common interest, with similar levels of obsession for that interest. Perhaps its value lies in the accumulation of social capital through participating in this community.â€

s argument, “What, then, do you think of people who make webisodes and short films on YouTube? The value in fan fiction seems to lie in the formation of community. The value of these communities lie perhaps not in economic capital. The Internet has enabled a platform on which people from geographically disparate areas can gather and form a community based on a common interest, with similar levels of obsession for that interest. Perhaps its value lies in the accumulation of social capital through participating in this community.â€

Or something like that. Iâ€ m paraphrasing in quotations here.

m paraphrasing in quotations here.

There seemed to be two points here. On one hand, we were talking about real life versus fictitious life, and the time and energy invested in exploring fictitious worlds. My friend seemed to think that unless one is getting paid for their fantasy explorations, such explorations and expansions of pre-existing worlds are not legitimate uses of oneâ€ s life and oneâ€

s life and oneâ€ s time, and that one must only partake in these communities because oneâ€

s time, and that one must only partake in these communities because oneâ€ s real life sucks. This leads to the other point – the point about community in fan fiction, and the very real emotional investments people have in characters and their stories. Walt Fisher, through the narrative paradigm, talks about the “cognitive significance of aesthetic communication lies in its ability to manifest knowledge, truth or reality, to enrich understanding of self, other, or the world.†(Fisher, 1989, 13) Human truth or reality includes emotions and feeling. Fiction writing, being a form of aesthetic communication, ties itself to these human emotions, rendering them real through the narrative storytelling process.

s real life sucks. This leads to the other point – the point about community in fan fiction, and the very real emotional investments people have in characters and their stories. Walt Fisher, through the narrative paradigm, talks about the “cognitive significance of aesthetic communication lies in its ability to manifest knowledge, truth or reality, to enrich understanding of self, other, or the world.†(Fisher, 1989, 13) Human truth or reality includes emotions and feeling. Fiction writing, being a form of aesthetic communication, ties itself to these human emotions, rendering them real through the narrative storytelling process.

In fan fiction, writers use familiar characters, popularized on television shows, as a means by which to explore deeper narrative plots and emotional entanglements, mostly for entertainment, but through a narration, and through sharing the narration, and interacting with others, a community is formed. Sometimes the community, like The L Word fan fiction community, are built around members of marginalized social groups (in this case, lesbians and queer women), giving people a space in which they can explore or affirm their identity among people who understand. Some of these people are geographically located in areas where being not heterosexual is not ok. Fan communities, then, provide them with a space filled with people who are like them and who will not stigmatize them for who they are or what they enjoy as entertainment. In a community of obsessors, no one is one.

Fan fiction and fanvidding (wherein people use actual clips from TV shows and remix and re-edit them to tell a narrative), have long been considered stigmatized. As my friend stated, it has a reputation for being the socializing grounds for people who donâ€ t have lives offline. An L Word fan fiction writer with whom Iâ€

t have lives offline. An L Word fan fiction writer with whom Iâ€ ve had conversations keeps her fan fiction writing from her family. Similarly, a maker of L Word fan videos with whom I have corresponded, keeps her fanvidding life behind closed doors. One is conventionally known only by oneâ€

ve had conversations keeps her fan fiction writing from her family. Similarly, a maker of L Word fan videos with whom I have corresponded, keeps her fanvidding life behind closed doors. One is conventionally known only by oneâ€ s username on fan fiction sites. Perhaps in the case of the L Word, there is the added stigma of dealing with homosexuality in the stories, in a time and world in which being gay or lesbian, or queer, is still stigmatized, or at the very least, marginalized.

s username on fan fiction sites. Perhaps in the case of the L Word, there is the added stigma of dealing with homosexuality in the stories, in a time and world in which being gay or lesbian, or queer, is still stigmatized, or at the very least, marginalized.

The L Word fan fiction seems to have a double-whammy effect in terms of its marginalization. First, itâ€ s fan fiction. Second, itâ€

s fan fiction. Second, itâ€ s fan fiction based on a show filled primarily with members of a marginalized social group (lesbians).

s fan fiction based on a show filled primarily with members of a marginalized social group (lesbians).

When Showtimeâ€ s TV series, The L Word, first aired in 2004, it was hailed, on one hand, as a “groundbreaking†show which had a cast and plots centered around lesbians and their lives, and on the other, as a squandered opportunity, stereotypically Hollywood with their skinny portrayals of characters, that does injustice to the lesbian community as a whole. (http://www.offourbacks.org/LWordRev.htm) Shortly after the inception of the show, fan fiction communities sprung up on the Internet with stories revolving around the characters in The L Word, many addressing the unsatisfactory handlings of the canon storyline as seen on Showtime. The most popular of these is a site that is aptly named “The L Word Fan Fiction†(http://fanfiction.l-word.com/fanfiction_list.php). One of the more popular coupling on the site is Bette and Tina, a canonical couple who, in the canon storyline, had started out as a committed couple, and, after six years of twists and turns, end up back together. Many people on fan fiction sites see them as the epitome of love. Throughout the six canonical TV seasons, there are a few moments or events that happen that I call “points of trauma.†For the Bette and Tina relationship, there are about 3-5 major ones. Iâ€

s TV series, The L Word, first aired in 2004, it was hailed, on one hand, as a “groundbreaking†show which had a cast and plots centered around lesbians and their lives, and on the other, as a squandered opportunity, stereotypically Hollywood with their skinny portrayals of characters, that does injustice to the lesbian community as a whole. (http://www.offourbacks.org/LWordRev.htm) Shortly after the inception of the show, fan fiction communities sprung up on the Internet with stories revolving around the characters in The L Word, many addressing the unsatisfactory handlings of the canon storyline as seen on Showtime. The most popular of these is a site that is aptly named “The L Word Fan Fiction†(http://fanfiction.l-word.com/fanfiction_list.php). One of the more popular coupling on the site is Bette and Tina, a canonical couple who, in the canon storyline, had started out as a committed couple, and, after six years of twists and turns, end up back together. Many people on fan fiction sites see them as the epitome of love. Throughout the six canonical TV seasons, there are a few moments or events that happen that I call “points of trauma.†For the Bette and Tina relationship, there are about 3-5 major ones. Iâ€ ve noticed that many fan fiction stories revolve around explaining these points of trauma, expanding on the charactersâ€

ve noticed that many fan fiction stories revolve around explaining these points of trauma, expanding on the charactersâ€ actions and thoughts, sometimes to the point of psychoanalysis, and using re-narration and re-telling of the canonical story, and taking it in different directions, as a healing process – to heal both the characters, and the writers, who, being fans with real emotional investments in these fictitious characters, experienced the trauma as well.

actions and thoughts, sometimes to the point of psychoanalysis, and using re-narration and re-telling of the canonical story, and taking it in different directions, as a healing process – to heal both the characters, and the writers, who, being fans with real emotional investments in these fictitious characters, experienced the trauma as well.

I will be talking about these points of trauma in more specificity in a future blog post, as well as the interconnectedness and cross-references of the stories within the fan fiction community.

Just One of the Low Millions? 14 Feb 2011 8:37 PM (14 years ago)

Zombies are, for me at least, a rich subgenre of horror that allows us to explore a host of issues that deal with issues of politics, economics, and class. Even scholars who are only vaguely familiar with the topic can often cite the cultural critiques latent within George Romeroâ€ s Dead trilogy.

s Dead trilogy.

Over the past two years, our group has bandied about different concepts that deal with pop culture and the political, with mention of terms like “movements,†“groups,†and “masses†calling to mind the ways in which issues of power and powerlessness manifest in the zombie genre. Although we can talk about the larger ways in which horror intersects with notions of power, zombies, out of all the monstrosities, provide a more direct understanding of the relationship between individuals/communities and minorities/majorities.

In particular, I am curious about the ways in which zombies are being reinterpreted in modern culture: employed in the 1930s as symbols of colonialism, resurrected in the 1960s to showcase the ills of consumer culture, and tweaked in the 2000s to evidence fears surrounding biological agents, zombies have always been, in some ways, representative of a fear of being subsumed by the masses. And yet the rise in zombie subculture seems to have split in recent years: although we continue to preoccupy ourselves with surviving the impending zombie apocalypse (hint: take up parkour), we also seemingly exhibit an increased desire to become zombies through events like zombie walks/crawls. Moreover, looking to online spaces—which are, in their own ways, very much about communities—we also glimpse a thriving group of individuals who choose to play as zombies in various forms.

What does all of this mean for the ways that we consider ourselves in relation to the communities around us?

Although groups like Invisible Children seem quite distinctly different from zombies, I wonder about how individuals in both organizations negotiate their identity as members of a highly-visible subculture that, most likely represents a national minority, might at times be a majority in local societal contexts. Moreover, in both situations, we have (primarily) young people who toe the line between belonging to a group and maintaining a sense of individuality within the mass—or maybe members do not fear being “swallowed up†by the group at all.

The more that I learn about how zombie culture is being enacted and embodied in real world practices, the more that I think about how lessons for political action can be extracted and utilized. But then again, zombies have always been about politics.

Chris Tokuhama studies popular culture, youth, Suburban/Gothic Horror, and media as a graduate student in the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California while balancing a full-time job in the Office of College Admission. Primarily interested in modern mythologies and narrative structures, Chris has often reimagined the Scarecrow as a zombie. Comments, questions, and Starbucks gift cards can be sent to tokuhama [at] usc [dot] edu.

Possibilities for Engaged Scholarship 7 Feb 2011 3:35 PM (14 years ago)

Iâ€ ve been thinking lately about engaged and other forms of participatory scholarship and how it might apply to the work that weâ€

ve been thinking lately about engaged and other forms of participatory scholarship and how it might apply to the work that weâ€ re doing at Civic Paths. Engaged scholars are intentional in crafting a relationship with their work that includes a dedication and involvement with their subject matter; the scholar admits to becoming a stakeholder rather than attempting to remain objective and uninvolved. This kind of framing connects to a trend in qualitative methods where scholars deeply consider the potential impact of their work, and attempt to challenge the power dynamic that appears to so starkly distance researchers from their subjects. By engaging with participants in this way, researchers can also begin to employ different notions of traditional concepts like validity and voicing. For instance, new knowledge and findings can be validated by the participants, rather than just the researcher, and the voices of the participants can be utilized within the writing process alongside the voice of the researcher.

re doing at Civic Paths. Engaged scholars are intentional in crafting a relationship with their work that includes a dedication and involvement with their subject matter; the scholar admits to becoming a stakeholder rather than attempting to remain objective and uninvolved. This kind of framing connects to a trend in qualitative methods where scholars deeply consider the potential impact of their work, and attempt to challenge the power dynamic that appears to so starkly distance researchers from their subjects. By engaging with participants in this way, researchers can also begin to employ different notions of traditional concepts like validity and voicing. For instance, new knowledge and findings can be validated by the participants, rather than just the researcher, and the voices of the participants can be utilized within the writing process alongside the voice of the researcher.

Although our research collective sometimes shies away from discussing our relationship with organizations, it seems that there is a standard default that has been assumed—we are studying and learning from these organizations, and we are not intervening in their work in any way.  Whether or not it is intentional, this assumption upholds the position that we must remain academics, and they must remain practitioners, and that a divide exists between the two.  I would like us to question these assumptions, for a number of reasons. First, our process of growing knowledge and developing insights about how young people become civically engaged via participatory culture could be strengthened by a sense of collaboration and reflexivity, rather than assuming the traditional posture of the (knowing) academic and the (unknowing) subject.  Although I don’t feel that anyone actually believes that academics are superior to practitioners, we still need to consider the implications of choosing conduct our research in a traditional fashion.  Given the unique relationships that we already have with these organizations (for instance, that we present together at academic conferences), it seems natural to begin to question our own methodologies.  Moreover, it is safe to say that we already are stakeholders in the project of helping young people to become civically engaged—we have a firm opinion on the matter, which is that our society is improved when more people are civically engaged, and so we are invested in learning about this process so that we can find new ways to encourage others to do the same.

In my own work with the organizers at Racebending.com, I have found many similarities between myself and those that I study. With regard to research interests, we are both curious to know how to best utilize the energy and passion of fans toward a political movement. We both want to know what has been more successful and what has been less successful, and how we can move forward from here. With regard to method, we both consult professors and previous scholarship in order to educate ourselves about things like how Asian Americans have been represented in the media, and how the media impacts children. We are both interested in statistically surveying the participants at Racebending.com (although they do not have to pass through the IRB in order to do so), and in general want to know as much as possible about the reasons people have for joining and becoming active members.

Given that we share so much, it has made sense for me to approach my work with this group in a more participatory, collaborative fashion than traditional social sciences or humanities methods. Although plenty of articles have been written about the difficulties of such partnerships and the inequalities that remain even in doing so, I still think there is valuable ground to be gained in the effort—if nothing else, to actualize my commitment to queering research methodologies and boundaries within academic institutions.  I have shared my own thoughts and analyses about their organization in my academic writing, including critiques and questions that the leaders may not have come to on their own.  But they have also been able to push back–to explain themselves, to reflect, or to simply accept that we are each entitled to seeing the group through our own lenses and frameworks.  I’m not saying that we reached any great understanding or that our partnership amounted to positive change, but I do think that realizing and acknowledging our overlapping goals helped both of us to reconceptualize the processes of both research and activism.

With regard to Invisible Children, I am reminded of the way that individuals within the organization have repeatedly talked about their own difficulties in negotiating power dynamics. For them, their identity as a largely white, middle class American organization trying to help children in Uganda can all too easily fall prey to critique from outsiders—Who are they to tell the Ugandans what is best? How can they truly understand the experiences of another group of people? Arenâ€ t they just trying to capitalize on the suffering of others?  In their own daily struggles to negotiate their position as an advocacy organization, I see many similarities to the debate that I have outlined above. In that sense, I think that this conversation about who has the ability to theorize, speak widely, and impact social change would be of particular interest and resonance to them and other like-minded organizations.

t they just trying to capitalize on the suffering of others?  In their own daily struggles to negotiate their position as an advocacy organization, I see many similarities to the debate that I have outlined above. In that sense, I think that this conversation about who has the ability to theorize, speak widely, and impact social change would be of particular interest and resonance to them and other like-minded organizations.

Although this kind of work can be challenging and suffers from a unique set of problems, these are questions that I know our research group is ready to engage with. Â I am excited to see what possibilities we can imagine for conducting our work in a way that is beneficial, forward-thinking, and honest to all parties.

Definitions of Otaku and Hikikomori 12 Jan 2011 10:22 AM (14 years ago)

I was surprised at a wrong definition of Otaku listed on Urban Dictionary.com…

Otaku is defined in the Urban Dictionary as follows:

Otaku is the honorific word of Taku (home). Otaku is extremely negative in meaning as it is used to refer to someone who stays at home all the time and doesnâ€ t have a life (no social life, no love life, etc). Usually an otaku person has nothing better to do with their life so they pass the time by watching anime, playing videogames, surfing the internet (otaku is also used to refer to a nerd/hacker/programmer). (death_to_all, 2003)

t have a life (no social life, no love life, etc). Usually an otaku person has nothing better to do with their life so they pass the time by watching anime, playing videogames, surfing the internet (otaku is also used to refer to a nerd/hacker/programmer). (death_to_all, 2003)

Then I finally realize why some American people couldnâ€ t tell the difference between Otaku and Hikikomori.

t tell the difference between Otaku and Hikikomori.

Wikipedia listed more appropriate definition as follows:

In modern Japanese slang, the term otaku refers to a fan of any particular theme, topic, or hobby. Common uses are anime otaku (a fan of anime), cosplay otaku and manga otaku (a fan of Japanese graphic novels), pasokon otaku (personal computer geeks), gÄ“mu otaku (playing video games), and wota (pronounced ‘ota’, previously referred to as “idol otaku”) that are extreme fans of idols, heavily promoted singing girls. There are also tetsudÅ otaku or denshamania (railfans) or gunji otaku (military geeks).

So, English translation could be maniac or mania. Otaku people have a specific and profound interest in something and they can interact with other fans in person and online even though they talk and act in a geeky way. Otaku can be used positively to express their expertise.

On the other hand, Hikikomori people have sever difficulty in social interaction so that they stay at home all the time, have nothing better to do with their life, and pass the time by watching anime, playing videogames and surfing the internet as Urban Dictionary explains about Otaku people. I donâ€ t know how this misinterpretation started but it might be attributed to the honorific word of Taku (home) since the image of being at home can be connected the word, Taku.

t know how this misinterpretation started but it might be attributed to the honorific word of Taku (home) since the image of being at home can be connected the word, Taku.

The meaning of new terms created in popular culture is always changing and hard to define. While researchers have hard time to keep up with changes, the participatory culture like Wikipedia can take more prompt action about popular culture.

Akoha – a Direct Action Game? 30 Dec 2010 1:16 PM (14 years ago)

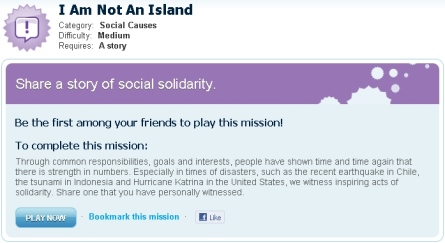

How can we make everyday civic participation more compelling? There is a new kind of game on the horizon, one that experiments with real-world action. I call them “direct action games,” because they restructure acts like volunteering, activist training, and charitable giving. One early prototype is Akoha, which launched last year, quite off the radar of traditional civics activities.

At first glance, Akoha looks like a media hub for a do-it-yourself Boy Scouts. Their website and iPhone app reveal thousands of participants, many reporting on success with real-world “missions,” from going vegetarian for a day, to debating the “I Have a Dream” speech. The actual missions often take place offline, but are only acknowledged when documented with photos and stories for the online community.

Participants are mostly adults, but the ages vary widely. The experience is deeply social, as friends create missions for each other, and share their stories. More formal recognition for participation comes as players earn badge-like awards — such as “multi-talented” for those who complete one mission in every possible category.

Yet most of Akoha does not look or sound civic. Only one of the mission categories explicitly addresses “social causes.” The other nine concern self-actualization in various forms, from “health and well-being” to family time, engaging with popular culture, and the discovery of travel. Is this breadth an upside or downside?  That depends on your civic goals, which might include:

- Fostering citizen journalism, as participants report on civic themes in their communities

- Informal civic learning, as participants reflect on their civic experiences in new ways through stories and pictures

- Building social capital, as participants create new ties across traditional social groups

These civic goals may be structurally possible with Akoha, but they are rhetorically hidden. Even as Akoha’s missions bring people into the real world, they avoid the “we are purely civic†framing that occurs on many activist and volunteering websites. For the Akoha community, itâ€ s OK to admit that you are mainly there to have fun, or are trying to improve yourself (and not simply sacrificing for others). Consider this screenshot from the social cause mission “I Am Not an Island”:

s OK to admit that you are mainly there to have fun, or are trying to improve yourself (and not simply sacrificing for others). Consider this screenshot from the social cause mission “I Am Not an Island”:

Participation begins with the usual click of a button, yet the specific language of “Play Now” differs sharply from the tool focus of civic action websites (e.g., “Take Action Now;†or “Sign the Petitionâ€).  But what exactly does it mean to ‘play’ Akoha? Is it a game?

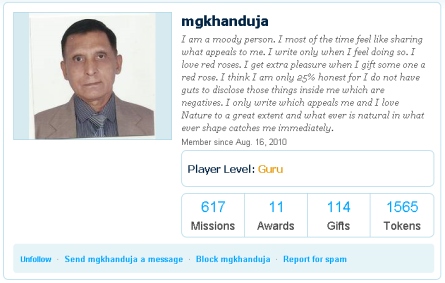

Certainly Akoha is recreational, and like all games, there are rules. In particular, participants must describe what they did to complete a mission, and thus must certify that they have met the terms set forth by the original mission author. Points and profiles track progress across the Akoha system. All players’ profiles feature their picture, personal statement, and a quantitative scoreboard — including their “player level,” number of missions completed, and awards.  For a sense of what this looks like, here is one particularly high-achieving player, chosen from among the more than 10,000-plus who have registered:

This profile has evolved much as the community has coalesced. Just a few months prior, the player described himself in much more formal terms, emphasizing his offline profession — a “freelance Air conditioning and Refrigeration engineer by qualification and profession,” his belief in God, and how he found the site via Reader’s Digest. Now, in this recent screenshot, the player has removed his back story, and describes how his Akoha playing strategy is driven by his personality. His refined self-presentation aligns with the pragmatics of the Akoha community, which focuses on choosing missions and writing stories — both depending more on personality than professional accomplishments beyond the community.

Akoha is a designed system, and so earlier this year, I interviewed Alex Eberts, co-founder of Akoha and an influential force behind its design. He spoke of his desire to find “psychological drivers that are common to the real-world, and to game play.” His designs were informed by self-determination theory, which Eberts first came across in a session at the Game Developers Conference. (Academics, pay heed – these are not the usual dissemination channels for civic theory.)

Self-determination theory describes how human motivation is driven by basic human needs, including competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Altruism is not on the list of needs, just as it is not central to Akoha’s rhetoric. Pushing beyond traditional altruism in civic life is a theme that cuts across many of the projects studied by our research group — from the pop pleasure of Harry Potter, to the joy of diamonds as a precursor to political talk. Repositioning altruism is a battle, with fault lines between traditional civic organizations that have failed to engage youth, and new civic organizations that have failed to connect to politics. (See, for example, Bennett’s content analysis of youth civic websites.)

Connecting games with the real-world necessitates a basic immediacy. This immediacy also distinguishes Akoha from most civic games, which focus on education for future civic life or future civic action. Here, the action and education are both immediate. In other words, experiential education of the most authentic sort. The iPhone app for Akoha, released this past summer, underscores their immediacy -– here is a set of screen shots they provide:

Using the mobile interface, Akoha missions can be documented on a bus in real-time, or browsed from a neighborhood park. This is a fairly basic use of mobile, focused on interfacing with established Internet content, independent of geography. Yet Akoha’s mobile interface is only minimally aware of specific places.

Place matters, especially in civics. (The neighborhood of our birth strongly predetermines a host of life opportunities, from income to education and governance.)  By improving Akoha’s mobile support for place, its implications for civic activity would be more immediate and profound. In particular, Akoha might offer support for filtering missions for one’s own neighborhood, or connecting with players who are geographically nearby for joint missions, or simply allowing missions to release new clues when players arrive at specific locations.

Games are still discussed as individual indulgences. Yet increasingly, games are recognized as social forces. This is especially true for Akoha, where the social construction of value emerges over time, as a participantâ€ s “friends” share stories about their missions and accomplishments. Different communities are likely to form over time. It is not yet clear whether Akoha is dominated by preexisting networks of offline friends, or by more interest-driven networks of people who gather around a shared passion. This is a central debate around civic communities, and there is hope that Akoha may avoid the pull into left/right politics that Sunstein fears by providing a safe space for civic discussion.

s “friends” share stories about their missions and accomplishments. Different communities are likely to form over time. It is not yet clear whether Akoha is dominated by preexisting networks of offline friends, or by more interest-driven networks of people who gather around a shared passion. This is a central debate around civic communities, and there is hope that Akoha may avoid the pull into left/right politics that Sunstein fears by providing a safe space for civic discussion.

Reimagining place is important civic work, just like the reimagining of societal values, tax policy, and even collective heroes. The value of games is to restructure this civic work around different rules – intrinsic motivations of the game, aligned with the desires of everyday people. Sometimes people want an excuse to be more civic. In my interview with Eberts, he confessed that one of the big surprises for his team was how much everyday people wanted support for being even more explicitly civic with the activities and missions of Akoha. He hinted that future Akoha versions would expand support for civic engagement.

Even as mobile has reshaped the everyday experiences of place and time, so too we may see game-like activities begin to restructure the experience of public participation. Yet Akoha remains an “edge phenomenon†to both the civic and gaming communities. In the first case, nonprofits are still trying to understand games for training, let alone for direct action; in the second, the independent gaming community is struggling to understand games for art, let alone games that improve the real world. Akoha is likely to be seen as a risky investment for funders in either community. Thus the evolving Akoha business model may be as crucial as its innovations in civic participation, and is worth watching. Eberts hints that corporate engagement may be one area to watch.

More broadly, Akoha raises questions about the definition and implications of direct action games. This was the subject of a panel I organized this year at Games for Change. Here is a video of the panel, featuring game designer Tracy Fullerton and activist/scholar Stephen Duncombe.

This blog post raises several questions about Akoha in the context of direct action games, including:

- Can games help us re-imagine civic activity under a different set of rules?

- If only a portion of the activity is civic, how do we appropriately value our investment in the overall activity?

- Where is the psychology of civic participation aligned with that of playing games?

- When is it appropriate to teach citizens how to “game the system” of democracy, and of our communities?

The Tea Party movement 30 Nov 2010 1:35 PM (14 years ago)

Over the last few months, I’ve been helping to develop the group’s understanding of civic activism by US political groups on the right – conservatives and libertarians, broadly speaking. We’ve been particularly looking for examples which centre on encouraging youth movements through grassroots participatory practices and new media platforms. Of course, the most high-profile example of participatory politics identified with the American right today is the Tea Party phenomenon, which was hailed as potentially being decisive in the 2010 midterm elections (although the actual results were mixed). The Tea Party movement is actually neither a political party nor a unified movement although the numerous groups which compose it have a generally recognized shared agenda that supports smaller government and a reassertion of what is claimed to be the original or traditional values of the U.S. Constitution in American politics. Typically understood as first being catalyzed by the government response to the financial crisis of 2008 as well as opposition to proposed healthcare reform legislation, the Tea Party movement can be roughly characterized as being focused on economic and political libertarianism, with relatively little interest in the social issues that conservatives often prioritize. A card-carrying veteran libertarian might question the ideological consistency of Tea Party politics, however — seeing them as more culturally than philosophically driven.

Over the last few months, I’ve been helping to develop the group’s understanding of civic activism by US political groups on the right – conservatives and libertarians, broadly speaking. We’ve been particularly looking for examples which centre on encouraging youth movements through grassroots participatory practices and new media platforms. Of course, the most high-profile example of participatory politics identified with the American right today is the Tea Party phenomenon, which was hailed as potentially being decisive in the 2010 midterm elections (although the actual results were mixed). The Tea Party movement is actually neither a political party nor a unified movement although the numerous groups which compose it have a generally recognized shared agenda that supports smaller government and a reassertion of what is claimed to be the original or traditional values of the U.S. Constitution in American politics. Typically understood as first being catalyzed by the government response to the financial crisis of 2008 as well as opposition to proposed healthcare reform legislation, the Tea Party movement can be roughly characterized as being focused on economic and political libertarianism, with relatively little interest in the social issues that conservatives often prioritize. A card-carrying veteran libertarian might question the ideological consistency of Tea Party politics, however — seeing them as more culturally than philosophically driven.

While it has formed itself out of many different and distinct clusters from across the country, the movement is generally understood as favouring relatively leaderless, non-hierarchical and decentralized structures and processes of organization and communication. For example, as the National Journal has reported, a popular management book that is widely read by organizers within the Tea Party movement is The Starfish and the Spider by Ori Brafman and Rod Beckstrom (2006) which describes and contrasts the advantages and drawbacks of two ideal type models of organizations – the centralized, tightly controlled and hierarchical spider model and the dispersed, loosely networked and egalitarian starfish model. Many Tea Party members would consider their movement to be more like a starfish while more traditional political party structures are thought to to be more spider-like. Â The starfish model however would not have been so successful were it not for the crucial role played by new media platforms, and especially Web 2.0 social media – Tea Party organizations have prominently encouraged social media training for its supporters.

Of course, the Tea Party is also known for being controversial, with heightened political tensions on all sides. The movement has attracted much critical attention from those on the political left and centre — including accusations that the the movement is largely (consciously or not) motivated by the divisive politics of race and alarmism — although many critics seem to be still working through the process of making sense of the complexities of the Tea Party movement for themselves. There have also been prominent liberal commentators who have expressed partial or selective support for some Tea Party positions and initiatives, including the feminist Naomi Wolf and the cyberspace legal theorist Lawrence Lessig. There are critics of the Tea Party on the right too — for instance,  conservative commentator Ron Radosh has concurred with liberal Harvard historian Jill Lepore’s objections to the Tea Party’s understanding and use of the history of the American Revolution and the Founding Fathers. And while Republican Party representatives and politicians have increasingly and often successfully sought to work with Tea Party activists, there are tensions between the Republicans and the Tea Party movement and some gaps in mutual understanding. Alliances between the two are still fraught with debates over whether the traditional GOP establishment is co-opting a movement that prides itself on its grassroots origins and a philosophy of principle over party. Views amongst Tea Partiers are also decidedly mixed about those right-wing political celebrities who seem to be claiming a role in the movement: while there is significant skepticism about probable contender for the 2012 Republican Presidential nomination Sarah Palin, there is seems to be greater support amongst Tea Party activists for the Fox News television personality  Glenn Beck.

There are, I think, two characteristics of the Tea Party movement thus far which are of most interest as lines on inquiry for our research into the participatory civics:

- The evolution of grassroots identity. The Tea Party movement famously understands itself as fiercely proud of its amateur grassroots identity and origins – it is widely recognized as one of the most successful popular political movements in America in recent decades. Anecdotes of movement supporters becoming interested in politics for the first time in their lives are a staple of coverage of the movement. However, as the movement has matured, a substantial amount of the grassroots political activity originally sparked seems to have faltered or has turned out to have been limited in its engagement in political processes — as highlighted by a recent Washington Post investigation. At the same time, the GOP and the well-funded and long-established networks of think-tanks and professional political activism organizations on the right seem to be playing an ever greater role in the movement despite the anxieties of many Tea Party organizers who are protective of the movements’ grassroots identity. What can the experiences of the Tea Party movement tell us about the evolution of the meaning of “grassroots” in the life cycle of a popular political movement?

- The curious lack of young Tea Party activists. As Meghan McCain has complained, the Tea Party seems to have struggled to attract and retain young activists.

While it is true that the demographics of the Tea Party movement seem to closely track those of the general U.S. population, it is striking to compare it with the “Obama-mania” of 2007-8 as well as with Republican Senator Ron Paul’s “Re-LOVE-ution” libertarian “insurgency” in the same period. Both those movements were seen as grassroots successes (albeit with support from traditional political structures) with strong internet and new media components – and both were understood largely driven by younger participants. This was especially so in the case of Ron Paul’s campaign which is curious given that many of his positions (and those of his son, Republican Senator-elect Rand Paul) are roughly sympathetic with those espoused by Tea Party movement supporters. What can the Tea Party case tell us about youth participation on the right in America? Grassroots youth interest in libertarian groups appears to be strong so why has the Tea Party not (so far) attracted more young voters and activists?

While it is true that the demographics of the Tea Party movement seem to closely track those of the general U.S. population, it is striking to compare it with the “Obama-mania” of 2007-8 as well as with Republican Senator Ron Paul’s “Re-LOVE-ution” libertarian “insurgency” in the same period. Both those movements were seen as grassroots successes (albeit with support from traditional political structures) with strong internet and new media components – and both were understood largely driven by younger participants. This was especially so in the case of Ron Paul’s campaign which is curious given that many of his positions (and those of his son, Republican Senator-elect Rand Paul) are roughly sympathetic with those espoused by Tea Party movement supporters. What can the Tea Party case tell us about youth participation on the right in America? Grassroots youth interest in libertarian groups appears to be strong so why has the Tea Party not (so far) attracted more young voters and activists?

Zhan