Ozempic: Save Money By Buying Through Canadian Internet Pharmacies 21 Mar 2023 9:10 AM (2 years ago)

Part of a CtWatchdog series on the high cost of drugs and medicine in the United States

There is good news for the millions of people who want to take Ozempic – the hot selling diabetes and weight loss drug from Danish drug firm Novo Nordisk – as it is again available in many pharmacies.

Americans who take the once-a-week injection and those who want to start can now obtain the medication.

The once-a-week injection, originally invented to fight Type 2 diabetes, has been unavailable because of huge demand from those who want to use it for its side-effect – losing weight – as well as manufacturing issues.

The medication is expensive – about $1,000 – for a four-week supply. Even using GoodRx, the cost is only slightly less. Many insurance companies won’t cover the medication since it is frequently only used to lose weight, what they consider is a cosmetic procedure.

The company does provide the medication much cheaper for low-income patients.

Ozempic is one of three injections developed over the past few years that will help reduce weight. All have been in short supply. There is also a medication – daily pills – which helps manage blood sugar levels and reduce weight.

As with all medications – even aspirin – there are side effects and potential serious health effects. We will discuss that further as well as how the medications work.

And, this is really important, if you stop taking any of these medications, you will PUT THE WEIGHT BACK ON – something that is not well publicized.

Save By Buying From Canada

For those who are forced to pay full price or have high deductibles, there is an alternative that will save hundreds of dollars – buying through Canadian internet pharmacies that specialize in serving Americans.

They are the same medications, but because Canada has price controls, it is a lot cheaper. While technically illegal for Americans to purchase medicine from Canada, our government looks the other way as long as you are only purchasing a maximum of three months supply.

I have been purchasing brand-name medicines from Canada for many years – saving as much as 90 percent on some.

For instance, at BuyCanadianInsulin.com, Ozempic costs $340 – plus shipping in special ice-cold containers – for a four week supply. Because of the shortage in Canada, you can only purchase one four-week pen at a time from this company.

Through Canadadrugsdirect, you can purchase up to two pens for $390 a pen, with a 10 percent coupon for the purchase of the first pen. Shipping is included.

I have purchased Ozempic from both companies without any issues. In full disclosure, I own 300 shares of Novo Nordisk, which sells three of the four diabetes and weight reduction medications. The fourth is Eli Lilly, whose drug – Mounjaro – is the most potent and is made specially for the obese. I own 200 shares of the company.

Personal Experience

My doctor wanted me to reduce my weight and to reduce my A1C as I am pre-diabetic.

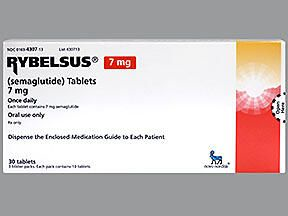

RYBELSUS ALTERNATIVE

He first prescribed Rybelsus, which has the same chemical makeup as Ozempic, but even its highest dose is less powerful.

With Rybelsus – which is cheaper at $830 for a 90-day supply through Canada – I lost 10 percent of my body-weight – and my A1C dropped by close to 7 percent.

At the same time, I increased my exercise and drastically cut back on sugar and processed food. To get the full effect, those steps should be taken by everyone. Rybelsus is covered by many insurance companies and by most Medicare plans.

I switched to Ozempic for the convenience of having to give myself only one injection (the needle is so small it’s hard to even see) a week, instead of taking daily tablets. You can’t drink or eat anything for 30 minutes after taking the pill.

I lost a couple of more pounds with Ozempic using 1mg a week.

Ozempic is available in 2mg, 4mg and 8mg pens. Only the 2 and 4 mg pens are available now in Canada.

I was able to purchase an 8mg pen through my local pharmacy earlier this month, with my Medicare drug part D covering more than half the American price. That pen will last for eight weeks as I continue to only use 1mg a week.

Interestingly enough, the cost of all sizes of Rybelsus and Ozempic are the same. So it makes sense to have your doctor prescribe a larger dose. The manufacturer says you aren’t supposed to split the pills but I have always disregarded such cautions. There is no such warning for the pens. Just keep in mind that the pens need to be refrigerated until ready for use.

Once its out of the refrigerator it has a 56-day lifespan.

HOW IT WORKS

Ozempic, Wegovy, and Rybelsus all use semaglutide as their key ingredient.

For weight loss, Wegovy is the most powerful as it contains the highest amount of semaglutide. The company said it is now available in many pharmacies. I have not found it in Canada.

Mounjaro, which is considered by some scientists as the most effective medication for those who are obese, has shown to reduce weight by as much as 22 percent in its highest dose. And it is again available in many U.S. pharmacies.

Drugs.com says:

- Both Mounjaro, from Eli Lilly, and Ozempic, from Novo Nordisk, are currently approved to help control blood glucose (sugar) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes, in addition to diet and exercise.

- Ozempic is also approved to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events (like a stroke or heart attack) in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus and established cardiovascular disease.

- Wegovy, from Novo Nordisk, is approved as an adjunct to diet and exercise for chronic weight management in adults and teens.

The medications work two ways to reduce your desire to eat a large amount and unhealthy food. First, they slow down how fast food travels through the digestive track, and they also send a message to your brain signalling that you are full.

Eating fried or sugary food or more than small portions will also result in kicking in side effects like nausea.

Side Effects

For several weeks after starting Rybelsus I had gastrointestinal issues: constipation, stomach pain and some nausea. Most of the issues went away, with the exception of sometimes having constipation.

Not unusual.

“Gastrointestinal (digestive tract) side effects are the most common side effects reported in at least 5% of patients with these medications,” says drugs.com.

“Nausea, diarrhea, decreased appetite, vomiting, constipation, indigestion (dyspepsia), and stomach (abdominal) pain have been reported. In some patients, gastrointestinal side effects can be severe enough to lead to treatment discontinuation.

“The labeling carries a Boxed Warning for possible thyroid tumors, including cancer, which has been seen in animal studies. Do not use Mounjaro if you or anyone in your family has a history of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), or if you have an endocrine system condition called Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN 2). Discuss this further with your healthcare provider.”

Also, Canpharm.com in Canada warns:

Mounjaro side effects may occur, and some users may experience dizziness or light-headedness, blurred vision, anxiety, irritability, or mood changes, sweating, shakiness, weakness, headache, elevated heartbeat, or feeling jittery. If Mounjaro side effects are seen you may want to stop use and speak to your doctor again regarding diabetes treatment medication alternatives.

I have not found a Canadian internet pharmacy that sells Mounjaro, but Ely Lilly says the medication is now available in many American pharmacies.

The post Ozempic: Save Money By Buying Through Canadian Internet Pharmacies first appeared on National Consumer News | Educating and helping U.S. consumers | Disclose Fraudulent Advertising | Providing News On Lowest Prescription Prices |.

East Hartford Pediatrician Surrenders License Rather Than Face State Charges For Illegally Prescribing Opioids, Med Board Fines Doc 20 Dec 2022 12:14 PM (2 years ago)

By Kate Farrish

RECOMMEND TWEET EMAIL PRINT MORE

An East Hartford pediatrician who served a federal sentence for illegally prescribing oxycodone and failing to pay more than $177,000 in employee withholding taxes to the IRS has voluntarily surrendered his medical license.

Since Dr. Sheikh Ahmed of Orange, who operated the East Hartford Medical Center, has turned in his license, the state Medical Examining Board on Tuesday agreed to drop its charges against him. If he tries to reinstate his license in the future, the charges will be deemed true, according to an affidavit from Ahmed.

State Department of Public Health records accuse Ahmed of engaging in illegal and negligent conduct by prescribing oxycodone, an opioid painkiller, to people in exchange for money without examining them in 2017 and 2018. He also increased their dosage of the drug without justification, DPH records show.

The U.S. State’s Attorney’s office said in 2020 that two people paid Ahmed $500 for 30-day supplies of oxycodone. It added that he counseled the people to increase the dosages gradually to avoid scrutiny from pharmacists. The ages of the people are unclear, but records show he treated adults as well as children.

Ahmed was arrested in 2018, and in 2019, he pleaded guilty to one count of prescribing outside the scope of medical practice and one count of willful failure to pay withholding taxes, federal records show.

In 2020, U.S. District Judge Victor A. Bolden in Bridgeport sentenced Ahmed to six months in prison, followed by three years of supervised release. The U.S. Attorney’s office said he had paid back the money he owed to the IRS. Federal court records show that Ahmed’s prison sentence was delayed three times for health reasons until at least September 2021, but federal prison records show he was released from custody on Feb. 2.

In an unrelated case in 2018, Ahmed was convicted of a state felony, health insurance fraud, for misusing his nurses’ Medicaid numbers and for falsifying medical records to make it appear that the nurses performed medical treatment that they had not performed, DPH records show. In 2013, the state Department of Social Services had terminated Ahmed as a Medicaid provider after investigating fraudulent Medicaid billing activity, DPH records show.

In other business Tuesday, the medical board fined a Hamden psychiatrist $5,000 for failing to adequately monitor a patient’s blood levels after prescribing medication between 2014 and 2019. Under a consent order the board approved, Dr. Enrique Tello Silva was also ordered to complete courses in patient communication and the management of patients on lithium, a drug used to treat mood disorders. Tello Silva chose not to contest the allegations, the order said. His attorney, Kevin Budge of New Haven, told the board that Tello Silva has taken the matter very seriously and has a “deepest regret” about the situation.

Before recusing himself from the vote, board member Dr. Robert Green said the fine was reasonable, but the board is seeing too many cases of doctors not properly monitoring prescriptions.

“Something went wrong and the patient suffered because of it,’’ Green said. “Prescription writing and monitoring is a huge problem not only in the state of Connecticut but in this country.”

In 2020, the board fined Tello Silva $5,000 and placed his medical license on probation for a year for failing to withdraw a patient from the use of Xanax on a safe schedule. The doctor, whose name was spelled as Tello-Silva on state records in that case, discontinued the patient’s use of Xanax in 2018 and didn’t provide the patient with adequate information about the drug, state records show.

Under that order, the doctor was required to hire another physician to monitor his practice for a year. He was also ordered to take courses in medical documentation and the proper prescription and discontinuation of benzodiazepines such as Xanax, the order said.

Tuesday, the medical board also reprimanded the license of Dr. Robert W. Behrends, a Waterbury psychiatrist, for prescribing more than a 72-hour supply of a controlled substance and failing to review the patient’s records in a drug monitoring program, according to a consent order approved by the board.

Behrends has completed courses in proper prescribing practices. In signing the order, he did not admit wrongdoing but chose not to contest the allegations.

Green objected to the reprimand as “nothing more than a slap on the wrist.” Behrends’ attorney, Mary Alice Moore Leonhardt of Farmington, said the patient in the case died. She added that Behrends has fully cooperated with DPH. She said he is winding down his practice and is “not one of these doctors out there prescribing like a cowboy.”

“The patient outcome was an extremely jarring experience for Dr. Behrends,’’ she said.

The board accepted the consent order by an 11-3 vote with Green and board members Michele Jacklin and attorney Joseph Kaliko voting no.

SUPPORT OUR WORK

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work.Donate Now

The post East Hartford Pediatrician Surrenders License Rather Than Face State Charges For Illegally Prescribing Opioids, Med Board Fines Doc first appeared on National Consumer News | Educating and helping U.S. consumers | Disclose Fraudulent Advertising | Providing News On Lowest Prescription Prices |.

No Longer A Pipe Dream: Connecticut In Line For $150m To Replace Lead Service Lines 20 Dec 2022 8:26 AM (2 years ago)

By Jenifer Frank

RECOMMEND TWEET EMAIL PRINT MORE

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Joseph Lanzafame, New London’s Public Utilities director, on Pequot Avenue where an exploratory “test pit” was drilled.

As soon as he heard that President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Act would include more than $4 billion to replace lead water pipes in the country, Joseph Lanzafame, New London’s public utilities director, knew two things:

First, no matter how much money Washington spent on the undertaking, it wouldn’t be enough.

And second, Lanzafame knew he wanted New London to be first on the state’s priority list for funding. “If we get out ahead of it,” he said, “we’re more likely to get additional subsidies … and we’re going to help set the standard for the state.”

Over the past two years, New London has been aggressively inventorying its pipes, the first step in the replacement process. Lanzafame has pored over historical records, hired engineers to do predictive modeling, and arranged for exploratory “test pits” to be drilled throughout the city to determine how many of its public water lines are made of lead.

“We have a significant portion out there,” he said. Last week’s estimate: More than a third of New London’s 6,500 service lines are lead.

‘It’s Historic’

Between 6 million and 10 million lead water pipes are in use today, most frequently in older cities and in homes built before 1986, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Lead pipes were used in the decades after the Civil War until the 1940s, and many have never been replaced.

Although lead paint and leaded dust and soil cause most of the lead poisoning cases in the country, especially among babies and young children, 20% of people’s exposure to the highly toxic metal is through drinking water, the EPA says.

Connecticut is slated to receive about $30 million in each of the next five years through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act to find and replace lead pipes with those made of copper, said Lori Mathieu, public health chief of the Drinking Water Section of the state Department of Public Health.

Although Lanzafame is correct that the federal money won’t cover anywhere near the cost of replacing the pipes, Mathieu is exuberant about the funding. “We’ve never seen this level of money,” she said. “It’s very exciting. It’s historic.”

DPH Photo.

Lori Mathieu, head of DPH’s Drinking Water Section, is overseeing the statewide lead pipe project.

The Inventory

Lead service lines are the pipes that connect homes, apartment buildings and businesses to water mains, which run down the middle of streets. The public side of the service line goes from the water main to a shutoff valve, or curb stop, at the property line, while the customer’s side goes from the shutoff valve to a home or business’s indoor plumbing.

Once test pits are bored at the point where the two sections meet, engineers can determine whether one or both parts of the water service line are made of lead. Engineering companies that specialize in statistically predictive modeling are hired so every water line in a municipality doesn’t have to be dug up. The cost of that would be “astronomical,” even in a small city like New London, said Lanzafame.

As it is, he estimated the total project cost for New London at $40 million over the next five years, though it could be lower with federal grants or principal forgiveness loans.

Social Vulnerability

Problems caused by lead pipes were most recently in the public eye during the 2014 water crisis in Flint, Mich. Officials in the cash-strapped city changed the source of drinking water from Lake Huron, whose water was treated, to the Flint River, whose water was untreated. The corrosive water flowing through lead pipes led to health problems throughout Flint and resulted in thousands of children under 6 registering high lead levels in their blood.

The Infrastructure Act requires “socially vulnerable” areas to be priorities for lead pipe replacement. The government’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, uses Census data such as socioeconomic level, housing conditions, access to transportation, and racial and ethnic minority status to identify Census tracts that need more resources to thrive.

However, Lanzafame said, “The SVI doesn’t have anything to do with the statistical model. The statistical model doesn’t care about color or race or economic situation, it just says lead line or no lead line.” As it continues to process information about the location of lead service lines, he said, the city will apply the social vulnerability index to the data. “So, people who happen to live in areas that are higher SVI are going to get their lines replaced first,” he said.

Poison In The Home

Unsurprisingly, many areas with high SVI rankings also have large numbers of lead-poisoned children. The CDC stresses that any amount of the heavy metal is unsafe, now defining lead poisoning as 3.5 micrograms per deciliter of lead or more in the bloodstream. Before May 2021, the CDC benchmark for lead poisoning was 5 micrograms per deciliter.

Melanie Stengel Photo.

This exploratory “test pit” is one of 150 drilled citywide to determine which pipes are lead.

In Connecticut, 3,000 children under 6 years old—nearly 5% of children in that age group—were reported as lead poisoned in 2020, the latest year for which the state DPH provides numbers. More than a third of those children lived in Connecticut’s poorest cities: New Haven had 376 poisoned children, Bridgeport had 298, Waterbury, 252, and Hartford, 171. That year, 58 New London children were poisoned. That was 12% of all of the city’s children under 6, one of the highest percentages in the state.

In 2020, using the CDC’s higher criterion for lead poisoning, 5 micrograms per deciliter, the state reported the number of lead-poisoned children at just over 1,000. The new, stricter, criterion of 3.5 micrograms triples the number of poisoned children that year to 3,000.

Babies and toddlers can be exposed to the heavy metal in vitro or if they drink formula made with lead-tainted water.

Before its use was banned in 1978, and despite common knowledge of its dangers, lead was added to both interior and exterior paint to increase its durability. Even if painted over, as it inevitably degrades, it can cause problems.

Young children are especially vulnerable to its dangers during these critical developmental years. With their hand-to-mouth exploring, they are more liable to ingest flaking paint chips or leaded paint dust, created by doors and windows in older housing opening and shutting, grinding down the paint. Soil near the base of older, dilapidated buildings is also frequently contaminated.

The CDC warns that even small amounts of the toxin ingested by children can cause “damage to the brain and nervous system, slowed growth and development, learning and behavior problems, and hearing and speech problems,” though these may not show up until years later.

Adults are also vulnerable to the toxin. Higher levels of lead can lead to cardiac and kidney problems, high blood pressure and fertility issues.

Looking To Newark

Earlier this year, as the state was gearing up for its lead service line project, the DPH’s Mathieu invited Kareem Adeem, director of the Water and Sewer Department in New Jersey’s largest city, to give a presentation to water district officials in Connecticut.

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Field service technicians check pipes on Pequot Avenue for lead.

When Adeem was named to his position in 2020, he was quoted as saying, “We are doing something no city in the country has done.” After several years of reports of dangerously elevated lead levels in its drinking water, Newark launched an intense program to replace every lead water pipe. In less than three years, it has replaced more than 23,000 lead lines.

In doing so, Newark became a model not only because of how quickly it worked but also because of how well it engaged its residents in the project. Most noteworthy, perhaps, is the website Newark created, which is filled with information on why the project was launched, advertising public sessions, explaining the health consequences of lead, where to pick up free water filters and water sampling kits, and dates and locations of the work.

New London

After studying the results from 150 test pits, Lanzafame said the city is just about ready to put its project out to bid. But before that happens, he needs to learn whether the city will receive any loans or, better still, subsidies.

“The good news,” he said, “is that the federal government and the state understand that lead service lines are a very big issue, they’re a very big cost, and there’s no way towns and communities could just do it without finding some other source of either funding or loans or something to extend it out.”

But because New London is No. 1 on the state’s lead service line priority project list, he’s feeling pretty optimistic.

The post No Longer A Pipe Dream: Connecticut In Line For $150m To Replace Lead Service Lines first appeared on National Consumer News | Educating and helping U.S. consumers | Disclose Fraudulent Advertising | Providing News On Lowest Prescription Prices |.

Winning Over Skeptics: More Police Departments Enlist Social Workers For Crisis Intervention 17 Dec 2022 10:53 AM (2 years ago)

By Carol Leonetti Dannhauser

RECOMMEND TWEET EMAIL PRINT MORE

Carol Leonetti Dannhauser Photo.

Caitlyn Cimmino and Tina Marie James, both Milford Police Department social workers, have responded to calls concerning domestic violence, breach of peace, larceny and other incidents. They are pictured with their supervisor Captain Garon DelMonte.

The 911 call came in from a parent whose son was threatening to kill himself. Typically, a police officer will race to a call like this, assess and stabilize the situation, and most likely request an ambulance to take the child away, leaving the family to pick up the pieces. In Milford earlier this year, that didn’t happen. Instead, the officer first summoned his colleague Caitlyn Cimmino, a licensed clinical social worker employed by the police department, and the pair dashed off together.

After the officer entered the home and ensured that the situation was safe, he invited Cimmino in to take over from there.

“It can feel a lot less intimidating to talk to a social worker,” said Cimmino, 27, who lives in Milford and has been working for the police department since January. The youth feared he was in trouble because police were called. “He said, ‘Is this thing going to be on my record forever?’ No, of course not. Just the sight of a police officer can frighten an individual, and fear can escalate a situation. It can feel more comfortable for them to talk to us.”

The visit ended not with the youth carted away by ambulance but with a connection via Cimmino to a therapist who could help and a promise by Cimmino to stay in touch with the family to make sure things were moving in the right direction.

When Cimmino was hired in January, the Milford Police Department became the second in the state, after Willimantic, to employ social workers in its ranks. Since the social workers were hired, the number of calls concerning mentally unstable members of the community has plunged, say officials from both departments.

Keeping The Troubled Out Of Trouble

The two departments are part of a small but powerful initiative called the Social Work and Law Enforcement Project, a statewide collaboration with a growing national reach whose aim is to help keep mentally unstable constituents out of trouble. Started by a former public defender social worker who became a college professor at Eastern Connecticut State University and the progressive police department down the road from her in Willimantic, SWLE embeds social work students as interns in police departments and trains them and police officers to work alongside each other.

The program has placed interns from Connecticut’s state universities, Sacred Heart University, the University of Saint Joseph and Fordham University, into the Willimantic, Milford, Middletown, Norwich and Stamford police departments over the past two years. Milford and Willimantic subsequently hired former interns early this year. Organizers believe it’s among the first training programs of its kind and a national model in the emerging field of police social work.

SWLE was born two months after the Connecticut Legislature passed the Police Accountability Bill in 2020 amid civil unrest following the murder of George Floyd by police during an arrest in Minneapolis. The bill mandated that police departments explore having social workers respond to calls and consider “employing, contracting with or otherwise engaging” them to assist police. The Connecticut State Police Union responded with a vote of no-confidence in Gov. Ned Lamont and the Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection after the bill’s passage.

But the pilot internship program began that fall in Willimantic and grew from there. Now, two years later, more and more police departments in Connecticut are enlisting social workers on site. The data, it seems, is turning skeptics into believers.

In their first six months as police department employees, Milford’s two police social workers, Cimmino and Tina Marie James, connected with 84 people suffering from mental distress, housing instability, addiction and more, who had called Milford police 683 times before the social workers were hired. Calls included help for domestic violence, larceny, psychological incidents, breach of peace, harassment and other incidents, according to Capt. Garon DelMonte, 36, a 15-year-veteran of the Milford Police Department who oversees the social workers.

Some people disconnected from reality would call 911 several times a day or at night. “It could be somebody experiencing paranoia or somebody delusional. Now, I can talk to Tina or Caitlin and say, ‘Hey, Johnny Smith called 14 times last night because he believed somebody was in his house. Will you talk to him?’” the captain said, adding that Milford police respond every time to every call, no matter how many times a person calls. “When we go somewhere and introduce a person that is not us, that is not capable of taking away somebody’s freedom, that will de-escalate the situation, maybe that person in crisis will say the police department is trying to help me here.”

Isabel Logan, a professor at Eastern Connecticut State University, is the founder of the Social Work and Law Enforcement Project.

A 2020 study by the Connecticut Sentencing Commission found that nearly 69% of people incarcerated in Connecticut have a history of mental health disorders.

Since the social workers were hired, DelMonte said, those same 84 people have accounted for 69 police calls. This tells him that the “implementation of social work services was successful to some degree in mitigating” the root causes of the initial crisis. “If we extrapolate these numbers out over the coming weeks, months, years, we should continue to see a great reduction of calls into the police department for individuals experiencing repetitive crisis.” He added, “Successful police work is the absence of problems, not numbers of problems.”

Who Will Call Tomorrow?

Social work and law enforcement run down the same highway in parallel lanes. Both are people-centered, communications-specialized vocations, DelMonte said. Police “go out and do all these great things … but who will call that person in crisis tomorrow? As much as we want to or try to, we just don’t have the time.” The social workers, he said, “provide the follow-up that is lacking in a law enforcement response.”

According to DelMonte, a social worker could have been helpful “hundreds of times” during his tenure, particularly in the detective bureau. “You think about the trauma of a sexual assault victim, or a juvenile, or a missing person. Almost every single one of those can benefit from a social worker.”

Milford’s chief, Keith Mello, chairs the state’s Police Officer Standards and Training Council and attended the state task force meetings on police accountability. After the bill was passed, there was a mandate but no template for exploring police social work. Mello learned about the fledgling program in Willimantic from its founder, Isabel Logan, Ed.D, LCSW, and signed on in the fall of 2021.

Logan, 48, had worked in the court system for 20 years, first as a social worker in the public defender’s office in New Haven, then at Hartford juvenile court.

“I was always driven by social justice, especially the intersection between social work and law,” said Logan, a Brooklyn native who grew up in the North End of Hartford.

She spent most of her career trying to prevent juveniles who had already been arrested from getting deeper into trouble, whether by setting up treatment programs for them to be released to, sending them to community programs or meeting with family members. “Anything possible to help clients not be in the system.”

Logan pursued doctoral studies at the University of Hartford at night while working by day. When a position opened at Eastern, she applied. She hoped to develop a prevention program. Just two years into her tenure, Steven Barrier, a Stamford man who suffered from various mental health disorders, died while in police custody in 2019. About seven months later, Floyd was killed, leading to calls nationwide and in Connecticut for police reform.

Spelling It Out

Logan felt she was in a unique position to do something about it. “I was interested in setting students up to work with police. I thought maybe we could help prevent people from getting arrested in the first place.” She had her students research police social work initiatives nationwide to help develop a framework. “We carefully carved out everything. Having a forensic legal background, I said let’s make sure we dot our i’s and cross our t’s. We documented everything,” she said.

Logan found a willing partner for her program less than a mile away. Lt. Matthew Solak, 45, was an 18-year veteran of the Willimantic Police Department and an Eastern alumnus. A proponent of community policing, he believed that many crimes would be prevented if constituents with mental health needs had better access to community services. Indeed, about 10% of service calls to police departments stem from someone with a severe mental illness, according to U.S. Department of Justice figures. “Law enforcement cannot arrest its way out of the problems mental illness creates in a community,” the DOJ report “Community Oriented Policing Services” concluded, “but can only address them by and through collective community effort.”

Solak lamented that police didn’t have resources to follow up with clients after a crisis. With the blessing of police Chief Paul Hussey, the Willimantic department agreed to pilot the internship program.

“You can’t just take a social worker and put them in a police car and expect it to work,” Solak said. “You have to identify someone who is interested in the work and in working seamlessly alongside your officers. That training component is really key. You have interns in emergency rooms, interns in hospitals, interns in schools. This is an extension of that.”

Logan and Solak created the first police social work academy in the country where social workers and police from the same department train together at the Connecticut Police Academy in Meriden.

Carol Leonetti Dannhauser Photo.

Social worker Emily Constantino was the first hired by the Willimantic Police Department. She is pictured here with her supervisor Lieutenant Matthew Solak.

Emily Constantino, Logan’s student for four years, was the first student placed. She now works full-time as a Willimantic Police Department employee. Constantino, of Coventry, said her family was skeptical when they learned of her placement. “In the summer of 2020, there were a lot of strong opinions about the police department,” she said. Beyond watching the TV shows “Law and Order” and “Brooklyn 99,” she didn’t know anything about police work and had never set foot in a police station, she said. “I remember thinking I can either watch what’s happening or go out into the community and try to do something. I felt like this was a really heavy responsibility.”

But after interning for 400 hours during her senior year at Eastern and 600 hours more as a graduate student at the University of Saint Joseph in Hartford, she was astounded at how many calls police departments receive that have nothing to do with criminal activity but with social issues concerning people in crisis. When the offer came to work full-time as a police social worker for the department, she signed on.

Word of their assistance is spreading throughout the community. Constantino arrived at the department one morning to find a woman sobbing in the lobby. The woman worked in town but had gone to the police department instead to escape her husband, who was abusing her and their children. Constantino connected the woman with the resources she’d need to escape, and her police officer partners took care of actions against the husband.

Making Things Different

Tina Marie James, 57, was studying for her master’s degree in social work at Sacred Heart University and working 12-hour weekend shifts in the psychiatric department at St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Bridgeport when Logan called about an internship in Milford in the fall of 2021. “I wanted to work in the community, but I’d never thought about the police department,” James said.

Her experience with police had been limited to one dreadful episode. When she was a youngster, James’s favorite uncle, who owned a candy store at Marina Village in Bridgeport, was robbed at gunpoint by four thieves. Her uncle had a gun, killed one thief, and maimed another. He was incarcerated for seven years. “All he’d wanted to do was be there in the neighborhood. Knowing the hurt that my mother felt and my cousins having to deal with the loss of their father, I realized I could assist in the process of making things different.”

Her friends weren’t so sure. “They were like, let’s address the elephant in the room.’ I’m an African American, middle-aged woman in a predominately white-employed police department. We know a lot of news with police officers, and it’s negative. It’s put a scarlet letter on the police department,” James said. “I’ve had one person say social workers shouldn’t be here. They think the police department should be defunded. But I think that right now, we as humans need to be more supportive and helpful. Social work is 80% listening. We have gotten away from that.”

Carol Leonetti Dannhauser Photo.

In Milford, social workers Caitlyn Cimmino and Tina Marie James respond to calls about housing insecurity, addiction and more.

James was hired full-time in February. She and Cimmino share space with the force’s crime prevention officers. They all work cooperatively with the city’s Human Services Community Outreach Workers and the Beth-El Center, a homeless shelter and soup kitchen.

While Milford and Willimantic are the only police departments in Connecticut that employ social workers, other departments maintain robust relationships with social workers. In Waterbury and Middletown, for example, police work hand-in-hand with embedded social workers employed by the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, which fields more than a dozen crisis intervention teams, some of whom operate out of police departments.

In October, Stamford police embedded a second social worker from the nonprofit group Recovery Network of Programs into their department. Based on Stamford’s success, Norwalk embedded its first social worker from RNP the same month. In her first 17 days on the job, that clinician, Alexandra Fitzner, followed up on 25 referrals from patrol officers.

In New Haven, an “unarmed emergency response team” stands ready to help police respond to 911 calls involving mental illness, substance abuse or homelessness. Elm City COMPASS, or Compassionate Allies Serving Our Streets, started in November and is funded with a $2 million federal grant. Hartford’s civilian response program, the Hartford Emergency Assistance Response Team, began last spring. HEARTeam responders include a mobile unit from the Capital Region Mental Health Center.

Fairfield police hope to become the third department to hire a full-time social worker. The job description includes everything from helping residents access mental health and addiction services to decreasing recidivism by “repeat consumers” to minimizing use-of-force incidents by officers.

A study by the University of Connecticut Institute for Municipal and Regional Policy found that 31% of people on whom police used force in 2019 and 2020 were reported to be “emotionally disturbed.”

Lt. Solak of Willimantic said his mental health unit is “serving citizens in a much more involved way. Having mental health as part of the police department is a sea change in law enforcement. It’s been fantastic.”

SUPPORT OUR WORK

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work.Donate Now

The post Winning Over Skeptics: More Police Departments Enlist Social Workers For Crisis Intervention first appeared on National Consumer News | Educating and helping U.S. consumers | Disclose Fraudulent Advertising | Providing News On Lowest Prescription Prices |.