Daaru as dawa: on liquor and its many uses in cinema 10 Apr 2:20 AM (6 days ago)

(An ex-colleague, the food historian and curator Anoothi Vishal, launched her dream project, The Food and Travel Almanac, a few days ago – and I got a chance to write for it. Here is my piece about liquor depictions, including the notorious Vat69 bottle, in Hindi cinema…)

------------------------ For someone who grew up in the shrine of popular Hindi cinema in the 1980s, and continues to find invigoration and meaning in that cinema – even its tackiest aspects – here is an indelible moment. Amrish Puri and Prem Chopra are seated in a dim-lit bar – the former looking villainous as villainous can be, the latter a bit subdued by his own high standards of leering bad-guy-ness, as if aware he is the sidekick here. Moments earlier the two men ran into sweet, fair-complexioned Meenakshi Seshadri. Now, as a waiter comes bearing a Chivas Regal bottle, Puri – in his booming voice – demands a Black Dog instead. Chopra asks for the reason behind this choice, and Puri replies with the immortal words: “Jiss din main koi gori titli dekh leta hoon, mere khoon mein sainkdon kaale kutte bhaunkhne lagte hain. Uss din main Black Dog peeta hoon.” (The English translation, which does no justice to the line, or to its grand delivery: “The day I see a white butterfly, many black dogs start barking together in my blood. Then I order a Black Dog instead.”)

For someone who grew up in the shrine of popular Hindi cinema in the 1980s, and continues to find invigoration and meaning in that cinema – even its tackiest aspects – here is an indelible moment. Amrish Puri and Prem Chopra are seated in a dim-lit bar – the former looking villainous as villainous can be, the latter a bit subdued by his own high standards of leering bad-guy-ness, as if aware he is the sidekick here. Moments earlier the two men ran into sweet, fair-complexioned Meenakshi Seshadri. Now, as a waiter comes bearing a Chivas Regal bottle, Puri – in his booming voice – demands a Black Dog instead. Chopra asks for the reason behind this choice, and Puri replies with the immortal words: “Jiss din main koi gori titli dekh leta hoon, mere khoon mein sainkdon kaale kutte bhaunkhne lagte hain. Uss din main Black Dog peeta hoon.” (The English translation, which does no justice to the line, or to its grand delivery: “The day I see a white butterfly, many black dogs start barking together in my blood. Then I order a Black Dog instead.”)

This has to be the rapiest product plug ever, goes a comment on a Reddit page, and who could disagree with that assessment? Even though this is a respectable mainstream film for the time – the Amitabh Bachchan-starrer Shahenshah, directed by Tinnu Anand, with a story credit for Jaya Bachchan (though one assumes she didn’t come up with the above dialogue!).

But then this was also a cinema of archetype and myth, with characters who were neatly classifiable as heroes and villains, victims and aggressors – as opposed to multi-dimensional people. In Shahenshah’s Wikipedia entry, Amrish Puri’s character JK is described simply as “the crime boss of Bombay” – which is exactly what he is. No detailing necessary. And in these films, alcohol often became an easy shorthand for vice. An unforgettable scene in the 1971 Elaan gives us, in just a few seconds, these wondrous sights: a topless Madan Puri (Amrish’s older brother) on a massage table, white-skinned girls in floral bikinis cooing over him, fake currency notes hanging from a ceiling… and on a nearby table a Vat 69 bottle, the ultimate symbol of perdition in a time of import restrictions and desh-drohi (nation-betraying) smugglers. But you could find similar things in dozens of other films. Dons stocked illegally procured liquor in their ornate lairs (to go with the spiky walls, rotating floors, acid pools or predatory sharks that made up the rest of the decor). Clinking Scotch glasses and cackling, they made diabolical plans; their molls, including the film’s main vamp, imbibed too, in between replenishing the glasses. She was a clearly defined counterpoint to the virginal good girl, the heroine.

And in these films, alcohol often became an easy shorthand for vice. An unforgettable scene in the 1971 Elaan gives us, in just a few seconds, these wondrous sights: a topless Madan Puri (Amrish’s older brother) on a massage table, white-skinned girls in floral bikinis cooing over him, fake currency notes hanging from a ceiling… and on a nearby table a Vat 69 bottle, the ultimate symbol of perdition in a time of import restrictions and desh-drohi (nation-betraying) smugglers. But you could find similar things in dozens of other films. Dons stocked illegally procured liquor in their ornate lairs (to go with the spiky walls, rotating floors, acid pools or predatory sharks that made up the rest of the decor). Clinking Scotch glasses and cackling, they made diabolical plans; their molls, including the film’s main vamp, imbibed too, in between replenishing the glasses. She was a clearly defined counterpoint to the virginal good girl, the heroine.

However, despite its archetypes, popular Hindi cinema could encompass different modes, provide multiple energies within the same film, and reach little truths within frameworks that are often dismissed as being “escapist entertainment”. In Deewaar, the brooding anti-hero Vijay shares a drink (and a smoke) in bed with his girlfriend Anita, a woman with an unsavoury past, identifiable as a vampish sort in the early scenes. On the surface, their cocktail of pre-marital sex, cigarettes, liquor and atheism (Vijay stays pointedly away from temples) spells Vice – we know these are not goody-two-shoes protagonists, and they won’t get a happy ending. The one time Anita says no to Vijay pouring her a drink, it is because she’s pregnant, and intending to enter a life of social legitimacy. And yet, even when they are living outside the law (judicial and societal), they are sympathetic figures, and we have more emotional investment in them than in the conventional romantic couple elsewhere in the film.

Meanwhile, an exuberant, fun-loving personality like Helen could cause us to rethink our notions about the vamp – especially when she was lighting up the screen, whiskey glass in hand, in musical sequences that transcended the rest of the film. Helen could even briefly tempt the Good Heroine into her shadowy world, as in a Gumnaam song where her character gets leading lady Nanda drunk and hic-hic-hiccing away. There are other special cases when it comes to the drinking woman. The once-straitlaced Choti Bahu (Meena Kumari) in Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam isn’t someone you’d expect to become alcoholic (she goes down that slippery slope in an effort to retain the companionship of her drunkard husband), but when this happens she remains a tragic, haunting figure for the viewer (even as she is condemned by her milieu). There are mild parallels here, incidentally, with an American film made that same year, 1962 – Days of Wine and Roses, in which a couple sink together into an alcoholic vortex.

There are other special cases when it comes to the drinking woman. The once-straitlaced Choti Bahu (Meena Kumari) in Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam isn’t someone you’d expect to become alcoholic (she goes down that slippery slope in an effort to retain the companionship of her drunkard husband), but when this happens she remains a tragic, haunting figure for the viewer (even as she is condemned by her milieu). There are mild parallels here, incidentally, with an American film made that same year, 1962 – Days of Wine and Roses, in which a couple sink together into an alcoholic vortex.

****

A few other manifestations of the Hindi-movie drinker bypassed the good-bad binary. There were those who were seen as existing outside the Indian mainstream – as in the stereotypical portrayal of Anglo-Indians as jolly eccentrics who always had a bottle in their hand (Prem Nath as the titular heroine’s father in Bobby, Om Prakash in a similar part in Julie). There were lovable character actors like Johnny Walker (supposedly a teetotaller in real life, despite his adopted name) and Keshto Mukherjee, who could slur and sway and bumble away comically without ever having to present the darker aspects of alcoholism.

And, above all, to use a common phrase of the time, there was the tragic hero or anti-hero, rendered brooding or self-pitying by unrequited love – the Devdas template, endlessly recycled through Indian-film history – or by the more general barbs of life, as was the case with Bachchan’s Angry Young Men from Namak Haraam onwards. Set against this, and often going alongside it, was the funny-drunk hero – though to pull this off you need someone with the comic skills of a Dharmendra (on the water tank in Sholay, or going crazy in the “Yamla Pagla Deewana” song in Pratigya with one hooch bottle tucked into his crotch and another in his hands). Or a Bachchan, who famously became a one-man army, often balancing the act of playing tragic drunk and comic drunk in the same film.

This brings me to another point: alcoholism in cinema – even the addiction variety, not just social drinking – can be more “fun” than alcoholism in real life. As a child I delighted in Bachchan’s many antics in films like Naseeb and Amar Akbar Anthony, and adored the “chooha-billi” song from Sharaabi – sung by a drunk hero, extolling the virtues of inebriation – despite the fact that in the real world I was frightened of an alcoholic father capable of violence. Someone else in this situation may understandably have been triggered, but for me the drunkenness of the characters on the screen was something abstract and removed; but it may also have been therapeutic in a way, substituting the “endearing” drunkard on screen for the one I was living with.

Naturally, as Hindi cinema has moved towards greater realism and sociological detail in the past two decades, there have been more nuanced depictions of alcohol and drinkers: films about people succumbing under work stress or peer pressure, or using liquor to submerge their loneliness (as the sad old professor, persecuted for his sexual orientation, does in Aligarh). But my childlike preference remains for films that manage to incorporate a certain over-the-topness in their liquor scenes.

**** Thematically, alcohol is associated with certain cinematic genres or sub-genres. For instance, drunkenness is a common motif in films with a redemption arc – where a washed-up cop or sports coach gets one more chance. Or a bomb-dismantler, as in the 1949 British film The Small Back Room where a scientist must help defuse a bomb while dealing with the demons that have driven him to alcoholism. What is notable about this film, made by the great team of Michael Powell-Emeric Pressburger, is that it merges kitchen-sink realism with surrealist fantasy. Though mostly a gritty, dialogue-driven production, it contains one scene – a nightmare of dislocation – with imagery worthy of Dali: conveying the hero’s fevered state of mind through twisted shadows, a ticking clock, and an impossibly large, misshapen bottle of liquor.

Thematically, alcohol is associated with certain cinematic genres or sub-genres. For instance, drunkenness is a common motif in films with a redemption arc – where a washed-up cop or sports coach gets one more chance. Or a bomb-dismantler, as in the 1949 British film The Small Back Room where a scientist must help defuse a bomb while dealing with the demons that have driven him to alcoholism. What is notable about this film, made by the great team of Michael Powell-Emeric Pressburger, is that it merges kitchen-sink realism with surrealist fantasy. Though mostly a gritty, dialogue-driven production, it contains one scene – a nightmare of dislocation – with imagery worthy of Dali: conveying the hero’s fevered state of mind through twisted shadows, a ticking clock, and an impossibly large, misshapen bottle of liquor.

Then there is the crime film. If the smuggling of imported liquor (among other things) was a trope of 1970s Hindi cinema, including the Angry Young Man films, internationally too alcohol has long been associated with the gangster genre. One can even argue that this major Hollywood form was founded on the liquor trade, with the first wave of 1930s gangster films (among them The Public Enemy and The Roaring Twenties, which made a superstar of James Cagney) dealing directly with Prohibition. Though perhaps the wittiest, most economical depiction of that era’s zeitgeist comes in the opening sequence of a much later comedy, Billy Wilder’s Some Like it Hot. This is an almost wordless car chase featuring a vehicle that seems to be carrying a coffin – until bullets hit the wood, liquid starts spilling out, the lid is opened to reveal not a body but dozens of bottles… and then the words “Chicago, 1929” appear on the screen, telling us all we need to know.

For every instance of liquor-consumption being associated with style or coolness – take James Bond and those countless shaken-not-stirred martinis – there have been reminders, even within popular films, of the ill effects: in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, Cary Grant –more suave than any Bond could be – is force-fed alcohol by the villains, to make plausible their story that he accidentally drove his car off a cliff.  There is a caveat here, though: while the film makes it clear that Grant has a drinking problem, part of the reason why he survives the murder attempt is that he is a habitual drinker with a very high threshold. In different ways, many films touch on this aspect of liquor – that it is harmful in obvious ways, but can be nourishing or life-enhancing in other ways. The Danish film Another Round – about a group of teachers in a mid-life crisis – presents a view of alcohol as something that can destroy lives, must be moderated, but can also make life more focused – and bring you closer to your real, unbridled self.

There is a caveat here, though: while the film makes it clear that Grant has a drinking problem, part of the reason why he survives the murder attempt is that he is a habitual drinker with a very high threshold. In different ways, many films touch on this aspect of liquor – that it is harmful in obvious ways, but can be nourishing or life-enhancing in other ways. The Danish film Another Round – about a group of teachers in a mid-life crisis – presents a view of alcohol as something that can destroy lives, must be moderated, but can also make life more focused – and bring you closer to your real, unbridled self.

Which brings us back to popular Hindi cinema and its intrinsic connection with “nasha”: both can offer escape into a realm where anything seems possible. Think about it: many of our song-and-dance sequences can be viewed as the constructs of an imagination high on possibilities. Or consider a two-fisted hero beating up the bad guys to restore order to an unfair world, and then in the next scene staggering about playing the fool. Maybe all that justice-dispensing is the fevered imagining of a man who has been turned into a superhero (in his own head) by booze. With that subtextual analysis, even a deliriously over-the-top Manmohan Desai film can seem like rigorous kitchen-sink realism.

And so, let the last word belong to a legendary character actor. In Amar Prem, as a pani-puri vendor is about to put imli ka pani into the little hollow “puri” for Om Prakash, the latter stops him, extracts a whiskey flask and says use some of this “pani” too. Masala cinema and liquor makes for an equally pungent combination.

A stoical cat, Bob Dylan, and a post-human world: quick thoughts on the animated film Flow 8 Mar 7:40 PM (last month)

(from my Economic Times column)

---------

Come Oscar season, those of us who aren’t too interested in the competitive debates – which film was “better”, who “deserved” to win – can still enjoy watching a bunch of the nominated works close together, and trace distant links between them: visual or aural ones, thematic ones. This year, I found myself thinking about the many monuments that human beings build for (and to) themselves.

These could be the actual physical structures – beautiful and grand (or ugly and grand) buildings (The Brutalist), or immense statues. Or the art: Bob Dylan’s epoch-altering songs (A Complete Unknown). Or religious conceits: intense discussions about the legacy of a just-deceased Pope, and what message the successor’s appointment should send the world (Conclave). Or an attempt to transcend the circumstances of one's birth, as in Emelia Perez.  Yet my favourite of this year’s Oscar-plated films is one that’s concerned with how temporary all our monuments can be (even though they seem so significant and long-lasting on the human time-scale). I went into the Latvian film Flow – winner for best animated feature – knowing it would probably appeal to me because it bypasses the anthropocentric worldview: being set in an apparently post-human world where a motley group of animals and birds contend with climate change. But I wasn’t fully prepared for the mesmerising visuals and the elegiac background music (composed by director Gints Zibalodis). The images of flood-waters effortlessly covering the highest man-made structures (and the tallest trees). The traces of Ozymandias-like hubris everywhere (but not a person in sight).

Yet my favourite of this year’s Oscar-plated films is one that’s concerned with how temporary all our monuments can be (even though they seem so significant and long-lasting on the human time-scale). I went into the Latvian film Flow – winner for best animated feature – knowing it would probably appeal to me because it bypasses the anthropocentric worldview: being set in an apparently post-human world where a motley group of animals and birds contend with climate change. But I wasn’t fully prepared for the mesmerising visuals and the elegiac background music (composed by director Gints Zibalodis). The images of flood-waters effortlessly covering the highest man-made structures (and the tallest trees). The traces of Ozymandias-like hubris everywhere (but not a person in sight).

Most of all, there is the film’s decision to have the animals communicate purely as animals – at least in terms of them not talking to each other. There are scenes – two rescue operations, for instance – that take the narrative forward by having the characters engage in human-like deliberation and planning. But a few other moments that might seem contrived or cutesy – e.g. a lemur meditating with hands spread out, or being possessive of the trinkets it has found – are rooted in the real-life behaviour of these creatures. The central figure in this story of survival and adaptation is a grey cat who is observer, anchor, and our point of identification – and it’s remarkable how much has been achieved with this character who barely has any “personality” as we’d normally define that term. The cat’s standard expression is a wide-eyed, fearful contemplation – punctuated by little mews – of everything going on in this watery landscape, and of the new creatures it has to interact with. There are a nice couple of moments where it is shown tapping into its essential “cat-ness” – sharpening its claws on the side of a boat, knocking something off a higher surface to the ground, playfully grabbing the lemur’s long tail. But this apart, it is mainly a spectator, who gets by on luck as much as initiative. (Curiosity keeps this cat alive.) I came to see it as a version of the deadpan Buster Keaton, navigating crisis after crisis, more bemused than heroic.

The central figure in this story of survival and adaptation is a grey cat who is observer, anchor, and our point of identification – and it’s remarkable how much has been achieved with this character who barely has any “personality” as we’d normally define that term. The cat’s standard expression is a wide-eyed, fearful contemplation – punctuated by little mews – of everything going on in this watery landscape, and of the new creatures it has to interact with. There are a nice couple of moments where it is shown tapping into its essential “cat-ness” – sharpening its claws on the side of a boat, knocking something off a higher surface to the ground, playfully grabbing the lemur’s long tail. But this apart, it is mainly a spectator, who gets by on luck as much as initiative. (Curiosity keeps this cat alive.) I came to see it as a version of the deadpan Buster Keaton, navigating crisis after crisis, more bemused than heroic.  But I also felt a kinship between Flow’s cat and the young Bob Dylan (played by Timothee Chalamet) in A Complete Unknown. Both are protagonists, everything pivots around them, they both move forward and the story follows them. And yet they are ciphers too, chronicling their times while also maintaining a detachment, an unwillingness to get too involved with the things everyone else around them is preoccupied with.

But I also felt a kinship between Flow’s cat and the young Bob Dylan (played by Timothee Chalamet) in A Complete Unknown. Both are protagonists, everything pivots around them, they both move forward and the story follows them. And yet they are ciphers too, chronicling their times while also maintaining a detachment, an unwillingness to get too involved with the things everyone else around them is preoccupied with.  The early-1960s folk music in A Complete Unknown is about very human concerns – the civil-rights movement, the addressing of many forms of social injustice. The beautiful background score in Flow, on the other hand, is like a majestic cosmic symphony, a tribute to the continuing glories of a world that may not have any people left. Such a contrast can be misleading, because the latter score did after all come from a human mind too – as did the sense of lament that runs through this beautiful film. However, it might be said that the greatest music in Flow is the undiluted sound of the natural world: water flowing gently or roaring by, animals and birds making their own urgent noises rather than speaking in human voices. A celestial score that would be beyond the efforts of even a Dylan.

The early-1960s folk music in A Complete Unknown is about very human concerns – the civil-rights movement, the addressing of many forms of social injustice. The beautiful background score in Flow, on the other hand, is like a majestic cosmic symphony, a tribute to the continuing glories of a world that may not have any people left. Such a contrast can be misleading, because the latter score did after all come from a human mind too – as did the sense of lament that runs through this beautiful film. However, it might be said that the greatest music in Flow is the undiluted sound of the natural world: water flowing gently or roaring by, animals and birds making their own urgent noises rather than speaking in human voices. A celestial score that would be beyond the efforts of even a Dylan.

An Irawati Karve biography + The Girl with the Needle: scattered thoughts 9 Feb 10:24 PM (2 months ago)

Highlights, apart from the talk and the readings, included a terrific saxophone performance by Tissa Khosla (Umi’s son) of “Mack the Knife” -- a song that was composed in Germany in the 1920s, a time when Irawati Karve was working there (measuring skulls because she was expected to prove the superior reasoning skills of white people; her research led to no such conclusion, and it nearly cost her a PhD and got her into trouble).

I also enjoyed the points that Umi made about the many contradictions and complexities in her grandmother’s personality (feminist in one context, seemingly not so much in another; with traces of both irreligiosity and religiosity), her ability to change her views over time — and how each generation feels the previous generation didn’t do enough in the name of progressiveness.

Have begun reading the book and am enjoying it - fast-paced, clear and thoughtfully written even when dealing with weighty subjects (and therefore “fun” even while dealing with morbid things).

Have begun reading the book and am enjoying it - fast-paced, clear and thoughtfully written even when dealing with weighty subjects (and therefore “fun” even while dealing with morbid things).On a related note: it often happens, when you’re reading books and watching films close to each other, that unexpected little connections arise between two unrelated texts. A recent example: in my new screening space in Panchshila Park last week, I watched the Oscar-nominated Danish film The Girl with a Needle, full of stark and haunting black-and-white frames – none more so than the images of the protagonist’s husband, who has returned home after being badly mutilated in the first World War (the film is set in 1919-20). And then, yesterday, I read in the Karve biography about Karve’s daily glimpse of just such a man, during her commute in 1920s Berlin; see the text here.

(I was also reminded of the two versions -- one filmed in 1919, the other in 1938 -- of Abel Gance’s J’Accuse, with the climactic sequence where real-life soldiers, many of them fearfully disfigured, play the role of dead soldiers who have arisen and march like zombies back to their homes…)

The little girl who lives on the edge – thoughts on children as adults onscreen 24 Jan 5:52 AM (2 months ago)

(Wrote this for my ET column)

------------------

Among my most satisfying viewing experiences of last year was a film I should have watched decades earlier – the 1976 thriller The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane, with 12-year-old Jodie Foster (she turned 13 during the shoot) as a girl who draws much attention from other townsfolk because she appears to be living by herself, her father mysteriously missing (*cue Twilight Zone music*). Shot a few months after Foster’s more famous, Oscar-nominated performance as a child prostitute in Taxi Driver, this role requires arguably an even greater display of poised “maturity”. I can’t discuss the plot without giving away spoilers, but suffice it to say that the protagonist Rynn runs a house and deals with adult visitors by herself, and even gets into a full-blown romantic relationship. And Foster is completely convincing throughout. She was a child prodigy in real life, hence perhaps well equipped to meet some of the demands of this part. But the fact remains – she was barely a teenager. Does this knowledge make some difference to our perceptions? Was the shoot a “safe space” for her (to employ an overused phrase of today)?

But the fact remains – she was barely a teenager. Does this knowledge make some difference to our perceptions? Was the shoot a “safe space” for her (to employ an overused phrase of today)?

There is a fleeting nude scene where Foster’s own older sister filled in as her body double – which means the adolescent was protected to a degree. But couldn’t that scene still result in a sexualising gaze directed at Rynn? What if a viewer doesn’t know about the body-doubling?

Then again, maybe this particular narrative is okay with such sexualising, maybe that’s even part of the point: the film is about a young person matter-of-factly leading an independent, self-sufficient life. In a sense the premise isn’t dissimilar from that of stories like William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, about children placed in a position where they are reorganising a world, without supervision. In such cases, conventional notions about age-related appropriateness might not apply.

Anyway I thought about Foster again when a friend and I, discussing Shuchi Talati’s new film Girls will be Girls, mulled that the young lead Preeti Panagrahi was 20 or 21 when it was made, around three years older than her character (a schoolgirl named Mira). A three-or-four-year gap between actor and character doesn’t seem like much, but within the adolescence-teenage bracket it can mean plenty: a 19-year-old playing a 15-year-old can feel off-kilter, unrealistic, even inappropriate, in a way that a 50-year-old actor playing forty wouldn’t. But there are also reasons for such casting, when a very young person is depicted in certain situations. (Girls will be Girls has a discreetly presented masturbation scene involving Mira, and another where she tries to figure out how to put a condom on her boyfriend.)

A fictional character can be shown as doing anything – within the plausibility of the world being depicted – but it’s a grey area to have under-age actors enact things they might not have actual life experience of. And strict guidelines, parental supervision and intimacy coordinators aren’t always enough. Even the TV series Riverdale, known for being edgy and subversive, mainly used performers who were in their twenties when the first season was shot. (KJ Apa, who played Archie, was the youngest at 19, but even he felt a little too well-built and jockish for the iconic red-headed high-schooler. And Cole Sprouse, as Jughead, was twenty-four going on sixteen.) We have come a long way (at least in mainstream films where many safety nets are in place) from the time when a six-year-old Shirley Temple was image-managed to be a wee replica of a glamorous adult star (to use Graham Greene’s controversial but accurate description, “infancy is her disguise, her appeal is more secret and more adult”), but even with the best intentions and more sensitised handling today, some scenes involving child actors can be discomfiting: e.g. 10-year-old Kiernan Shipka as Sally in Mad Men, “touching herself” while watching a TV show late at night; or a romantic kiss between Nicole Kidman and a child actor in Birth.

We have come a long way (at least in mainstream films where many safety nets are in place) from the time when a six-year-old Shirley Temple was image-managed to be a wee replica of a glamorous adult star (to use Graham Greene’s controversial but accurate description, “infancy is her disguise, her appeal is more secret and more adult”), but even with the best intentions and more sensitised handling today, some scenes involving child actors can be discomfiting: e.g. 10-year-old Kiernan Shipka as Sally in Mad Men, “touching herself” while watching a TV show late at night; or a romantic kiss between Nicole Kidman and a child actor in Birth. That said, some young performers are so canny and blasé in real life that lines get blurred. Auditioning for the lead in The Exorcist, 13-year-old Linda Blair casually said “she masturbates with a crucifix” while describing the film’s plot. A startled William Friedkin, after a glance at Blair’s real-life mother, asked the girl if she knew what that meant. “It’s like jerking off, isn’t it?” Blair said. “Have you ever done that?” Friedkin asked. “Sure, haven’t you?” Blair replied. Little wonder she got the part of the demon-possessed child.

That said, some young performers are so canny and blasé in real life that lines get blurred. Auditioning for the lead in The Exorcist, 13-year-old Linda Blair casually said “she masturbates with a crucifix” while describing the film’s plot. A startled William Friedkin, after a glance at Blair’s real-life mother, asked the girl if she knew what that meant. “It’s like jerking off, isn’t it?” Blair said. “Have you ever done that?” Friedkin asked. “Sure, haven’t you?” Blair replied. Little wonder she got the part of the demon-possessed child.

-------------------------------------

P.S. as it happens Jodie Foster had major roles in as many as FIVE films that were released in 1976 – including at least two, Bugsy Malone (which is constructed on the conceit of child actors playing adult roles) and Freaky Friday (mother-daughter switching bodies) that by their very nature require forms of “adult acting”. Because she had a career lull in the 1980s, it is easy to forget that her childhood acting stint was solid all by itself.

(Another somewhat related piece on child performers, in a Chaplin and Kiarostami film, is here.)

On the parent-child relationship in Girls will be Girls 17 Jan 2:07 AM (2 months ago)

(Wrote this piece about Shuchi Talati’s excellent new film for Economic Times)

-------------------

Often, our expectations for a film are raised so high beforehand that the actual viewing is a let-down. Three months ago I feared this would be my experience with Shuchi Talati’s Girls will be Girls. As the film won prize after prize at the Mumbai Film Festival closing ceremony, Talati, her young lead Preeti Panigrahi, and producers Richa Chadha and Ali Fazal trudged to the stage every few minutes – and the jokes flew fast. “Get them a conveyor belt!” someone next to me shouted. Manoj Bajpayee, who finally got up there for another movie (The Fable), quipped about it too, aiming a wisecrack at his Gangs of Wasseypur co-star Chadha.

Happily none of this build-up mattered when I did get around to watching Girls Will be Girls. To mangle a famous Groucho Marxism, “It looks like a good film, and has been acclaimed as a good film, but don’t let that fool you – it really IS a good film!” I was rapt all the way through – by the fluidity of the storytelling, each scene flowing organically into the next… and by the strong central presence. Panigrahi is exceptional as 18-year-old Mira, struggling to balance her image as the perfect, poised student with the inner turbulence caused by her growing romantic and sexual feelings for a classmate named Srinivas; meanwhile her mother Anila (Kani Kusruti, who gets to be more outwardly expressive here than in her gazing-into-the-middle-distance role in All We Imagine as Light) keeps a watchful eye on her, and sometimes seems too interfering.

I was rapt all the way through – by the fluidity of the storytelling, each scene flowing organically into the next… and by the strong central presence. Panigrahi is exceptional as 18-year-old Mira, struggling to balance her image as the perfect, poised student with the inner turbulence caused by her growing romantic and sexual feelings for a classmate named Srinivas; meanwhile her mother Anila (Kani Kusruti, who gets to be more outwardly expressive here than in her gazing-into-the-middle-distance role in All We Imagine as Light) keeps a watchful eye on her, and sometimes seems too interfering.

This is a slice-of-life narrative, but there are also passages of suspense in its depiction of Mira’s state of mind – such as a sequence where she is desperate to spend alone time with Srinivas (they are supposed to be studying together, he is staying overnight at her place) but her mother encourages him to sleep in her own room (further, Anila then locks the door so Mira will have to knock in the morning when she wants to wake him). Here and elsewhere, this unobtrusive film feels like a gripping thriller.

“A coming-of-age story” would be an easy descriptor – and yes, much hinges on Mira’s various awakenings, and on her recognition of her mother as anchor and protector – but Girls will be Girls is also one of those films that can shift texture, as if seen through a kaleidoscope, depending on how old you are when you watch it. The more intense scenes between Mira and Anila – and the viewer’s degree of empathy with either character – might unfold very differently if you are viewing them as a young person, as opposed to later in life. Mira’s perspective is the dominant one; we feel her frustration and anger. But it is entirely possible to look at things through Anila’s lens as well. As an almost-single parent, somewhat estranged from her husband but dependent on him financially (and answerable to him for Mira’s progress: “If your studies suffer, your dad will blame me – not you”), she is dealing with immense pressures. She has her own demons, loneliness and insecurity… and, blasphemous as it can be to suggest this, on occasion perhaps she envies her child too, growing up in a slightly more permissive time when it might be possible to get into a relationship quickly and then end it equally fast if it isn’t working out. “In our times, girls were not even considered,” is one of Anila’s first lines in the film – she is talking about the impossibility of a girl student being made head prefect, something her daughter has just achieved. But the statement has other applications. In a later, relatively unguarded moment, Anila talks about her own school days when the boys and girls were segregated and met only twice a year; about a boy hiding in a garden because he wanted to propose to her (they caught him, and she turned him down anyway). She is also clearly stung by Mira’s father joking that when *he* proposed to her at age 21, he was too young to know what he really wanted. While she is a responsible and concerned mother, she is also a human being capable of regret and bitterness, as any of us can be; lonely enough to monopolise the attention of a personable young boy in the process of shielding her daughter.

“In our times, girls were not even considered,” is one of Anila’s first lines in the film – she is talking about the impossibility of a girl student being made head prefect, something her daughter has just achieved. But the statement has other applications. In a later, relatively unguarded moment, Anila talks about her own school days when the boys and girls were segregated and met only twice a year; about a boy hiding in a garden because he wanted to propose to her (they caught him, and she turned him down anyway). She is also clearly stung by Mira’s father joking that when *he* proposed to her at age 21, he was too young to know what he really wanted. While she is a responsible and concerned mother, she is also a human being capable of regret and bitterness, as any of us can be; lonely enough to monopolise the attention of a personable young boy in the process of shielding her daughter.

This ambiguity, this hint of multiple motivations, is what I found most compelling about the film. There is a reminder here that some emotions – such as the excited anticipation of a new relationship (even a platonic one) – can stay constant across life stages. And that as youngsters we don’t realise that our parents – who can seem impossibly old and removed even when they are only in their thirties or forties – can have versions of the same yearnings and frailties that we do.

Akimitsu Takagi's crime fiction, in translation 30 Dec 2024 6:00 PM (3 months ago)

A classic locked-room mystery that I enjoyed very much: Akimitsu Takagi’s The Noh Mask Murder, originally published in 1949 and just translated into English (by Jesse Kirkwood) - it is now part of Pushkin Vertigo’s hefty catalogue of Japanese crime fiction. I was up well past midnight reading it a few days ago. It is creepy, a bit overwrought at times in its depiction of a messed-up family that may have a curse hanging over it – but very skilfully told overall. The narrative-within-the-narrative structure, and an ambiguity about who is the main detective and who the sidekick, adds to the effect.

There is also a hat-tip to an Agatha Christie novel, but it was done in an unusual enough way that it didn’t feel derivative. (Much like John Dickson Carr’s She Died a Lady – which offered an interesting variant on the Murder of Roger Ackroyd template – this book pays homage to an iconic work from the genre, but does something subtly different with the template.)

The most pleasing thing (and this is something fans of classic/Golden Age crime fiction might understand): with only around 20 pages left in the story, I was prepared for a bit of disappointment – it felt like the mystery would be too easily wrapped up, and the murderer’s identity an anti-climax; but then, in the final pages, a few ideas were overturned, making for a more complex ending. Late in the book, there is also an edgy conversation between two men, each accusing the other of being the killer, that was neatly done – as a reader one suddenly realises that everything the obvious/probable suspect is saying about the less obvious one’s actions could easily be true as well. Not easy to pull off that sort of two-hander.

P.S. I also read Takagi’s The Tattoo Murder a year or two ago, and had enjoyed that one largely for the elegance of the prose (something one doesn’t often find in even the most compelling of these mysteries; this translation is by Deborah Boliver Boehm) and the detailed information about the art and craft of tattoo-making. (It wasn’t surprising to learn that Takagi had taken many photos of the work of the major tattoo-makers of the 1950s, and eventually collected them in a book.) The locked-room solution in The Tattoo Murders felt complicated and confusing (which is true for many crime novels of that vintage, which rely on the reader’s knowledge of the mechanics of operating different types of doors and windows), but the book as a whole was terrific. Hoping more of his work is available in translation soon.

P.S. I also read Takagi’s The Tattoo Murder a year or two ago, and had enjoyed that one largely for the elegance of the prose (something one doesn’t often find in even the most compelling of these mysteries; this translation is by Deborah Boliver Boehm) and the detailed information about the art and craft of tattoo-making. (It wasn’t surprising to learn that Takagi had taken many photos of the work of the major tattoo-makers of the 1950s, and eventually collected them in a book.) The locked-room solution in The Tattoo Murders felt complicated and confusing (which is true for many crime novels of that vintage, which rely on the reader’s knowledge of the mechanics of operating different types of doors and windows), but the book as a whole was terrific. Hoping more of his work is available in translation soon.

Shyam Benegal – playful, curious, formally inventive 24 Dec 2024 8:07 AM (3 months ago)

(Wrote this tribute for Economic Times – drawing partly on a nice conversation I had with Mr Benegal in Calcutta in 2013)

---------------

In the aftermath of Shyam Benegal’s passing, much will be said about the social relevance of his work, and about his role as torchbearer for Parallel Cinema, bringing new content and themes, overt seriousness – and eventually even an alternate “star system” – to Hindi films in the 1970s. And yes, it is important to discuss his major work – Ankur, Bhumika, Mandi, so much else – in those terms. But when I think of Benegal now – the films, as well as a short meeting with the man himself in Kolkata a decade ago – what comes to mind is playfulness and lightness of touch. And a keen curiosity, even at an age when many people retire this ability.

Here is one moment from our conversation. Pushing eighty at the time, Benegal was talking about his work on an educational series for UNICEF before he began making feature films. One short film was about rainwater harvesting, about water bodies that disappear in summer, and he explained it by enacting it with childlike gestures, staccato sentences, pauses and emphases. “We did a story about a water-body in love with the sky. Burns with love. Evaporates into a cloud. Goes looking for the sky. Does not find the sky. Weeps, becomes rain. Wonderful things like this, combining science and fun.” I could scarcely believe this was the same person who made those “solemn” films I found daunting as a child.

At a celebration of his work in Bombay this year, when moderator Raja Sen asked the panellists about their favourite Benegal film, I could have gushed about a dozen of them, but picked the little-seen 1975 Charandas Chor, adapted from Habib Tanvir’s satirical play. Here is a film that – beginning with the opening-credit sequence where a donkey seems to wag its tail in tune to folk music – brings together elements of theatre and cinema with great brio. But though produced by the Children’s Film Society – and sometimes not treated as one of Benegal’s “mature” works – Charandas Chor isn’t alone in its formal inventiveness or sense of humour. There is much quirkiness in his other films too, which doesn’t take away from their basic seriousness.

Consider Mammo, which touches on Partition and those who were scarred by it – but also, being filtered through a child’s gaze, has moments like the one where the boy Riyaz gives his great-aunt Mammo a synopsis of Hitchcock’s Psycho, pretending it was a play called “Panipat ki Budhiya”. (Later, Mammo will get to tell her own horror story, from the Partition riots.) In a delightful touch, as Riyaz relates the plot, we hear Bernard Herrmann’s legendary Psycho score playing in the background. Even if this semi-autobiographical detail comes from writer Khalid Mohammed, the way in which the scene unfolds is typical of the playfulness that Benegal’s cinema doesn’t get enough credit for.

Consider Mammo, which touches on Partition and those who were scarred by it – but also, being filtered through a child’s gaze, has moments like the one where the boy Riyaz gives his great-aunt Mammo a synopsis of Hitchcock’s Psycho, pretending it was a play called “Panipat ki Budhiya”. (Later, Mammo will get to tell her own horror story, from the Partition riots.) In a delightful touch, as Riyaz relates the plot, we hear Bernard Herrmann’s legendary Psycho score playing in the background. Even if this semi-autobiographical detail comes from writer Khalid Mohammed, the way in which the scene unfolds is typical of the playfulness that Benegal’s cinema doesn’t get enough credit for. Or take Manthan, which has some pedantry and message-mongering built into it – being a celebration of the milk cooperative movement, and crowd-funded by lakhs of farmers. Yet the small moments are as telling as the big ones: a scene where a city slicker played by Anant Nag arrives at the village for the first time and looks for a spot to use as a toilet, while locals giggle as they watch him stumbling about, is a form of slapstick humour but also a depiction of the many ways of life that co-exist (or clash) in a complex, plural country. Which is what this film – and perhaps most of Benegal’s work – is also about.

Countless other whimsical moments and wry touches come to mind. The Bharat ek Khoj scene where Roshan Seth’s Nehru primly steps over broken weapons and other debris on the Kurukshetra battlefield before settling down to talk to us about the Mahabharata. The cleverly sinuous narrative of Suraj ka Satwaan Ghoda. It is also worth remembering – if you think Benegal neglected form for content – how carefully he worked with his cinematographers, to get the right look for a mood or setting. When he and Govind Nihalani were forced to use poor-quality Orwo film for Bhumika due to import restrictions (“There was a shortage of Kodak just as I was about to start,” he told me, “and I couldn’t buy more than a certain amount of Eastman Colour”), they made a virtue of necessity by creating a varying set of looks – one type of faded black and white for the protagonist’s childhood (which they also designed as a subtle homage to Ray’s Pather Panchali), another more vivid tone for the later scenes, colour for another time period. For Trikaal, set in an old Goan house before the state became part of India, Benegal and Ashok Mehta worked almost exclusively with candle-light, bringing alive not just the realistic segments of the film but also the unnerving inner world of the matriarch Dona Maria, who is visited by spirits and ghosts from a distant past. “Little islands of light in the darkness – that quality is what I wanted. We sat with different candle-makers to get different sizes and thickness of wicks, to suit the tone of a scene. We also re-watched European films with stories about Catholic orthodoxies, set in a similar period.”

Countless other whimsical moments and wry touches come to mind. The Bharat ek Khoj scene where Roshan Seth’s Nehru primly steps over broken weapons and other debris on the Kurukshetra battlefield before settling down to talk to us about the Mahabharata. The cleverly sinuous narrative of Suraj ka Satwaan Ghoda. It is also worth remembering – if you think Benegal neglected form for content – how carefully he worked with his cinematographers, to get the right look for a mood or setting. When he and Govind Nihalani were forced to use poor-quality Orwo film for Bhumika due to import restrictions (“There was a shortage of Kodak just as I was about to start,” he told me, “and I couldn’t buy more than a certain amount of Eastman Colour”), they made a virtue of necessity by creating a varying set of looks – one type of faded black and white for the protagonist’s childhood (which they also designed as a subtle homage to Ray’s Pather Panchali), another more vivid tone for the later scenes, colour for another time period. For Trikaal, set in an old Goan house before the state became part of India, Benegal and Ashok Mehta worked almost exclusively with candle-light, bringing alive not just the realistic segments of the film but also the unnerving inner world of the matriarch Dona Maria, who is visited by spirits and ghosts from a distant past. “Little islands of light in the darkness – that quality is what I wanted. We sat with different candle-makers to get different sizes and thickness of wicks, to suit the tone of a scene. We also re-watched European films with stories about Catholic orthodoxies, set in a similar period.”Filmmakers of Benegal’s generation – especially the ones who lived relatively privileged lives in cities while telling stories about exploited people – have often been accused of being disconnected from their subjects. Setting aside broader debates about representation, it is important to note that Benegal was aware of this disparity and worked it into some of his films, as a Fourth Wall-breaker. Samar uses a complex, nestling-doll structure to comment on hierarchies of privilege within the lower echelons of the caste system. (“I used the device of a film-within-the-film to look at the sensibilities of both Dalits who are deracinated in cities and those who are part of the original tradition. I couldn’t have done this as a straight narrative.”) Or here is Arohan, which begins with Om Puri, as himself, introducing the cast and crew, drawing attention to the artifice of what they are doing, before sliding into the story. Such moments show Benegal’s ability to hold a mirror up to himself – but equally, they suggest a dynamism that allowed him to move beyond plain realism into other realms. This makes his best work vibrant, alive and questioning in ways that transcend the staid term “art movie”.

(Related posts: Charandas Chor; Trikaal; Bharat ek Khoj; being underwhelmed by Kalyug)

An upcoming conversation with Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari 29 Nov 2024 2:35 AM (4 months ago)

This conversation – with Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari, author of one of the most acclaimed novels of the year, Chronicle of an Hour and a Half – is happening at Sunder Nursery, Delhi on Dec 6, at 4 pm. Please show up if you’re around. It is the first of this season’s Suitable Conversations curated by A Suitable Agency.

I read the book when it was published earlier this year, and was very impressed; but I think I have enjoyed it even more rereading it in the last few days for the discussion.

During that first reading, I had found the large number of characters – and their intersecting first-person narratives – a tiny bit confusing at first; but the book grew and grew in the telling, becoming an intense account of mob mentality and how it snowballs. The story, set in a small Kerala town on a very rainy day, is about the moralistic reactions to an adulterous relationship – between a middle-aged married woman and a young man – in a setting where matters of societal honour, the virtue of women and so on, become more important than individual autonomy or freedom of expression. It might be said that the author uses the honour-revenge motifs in Marquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold as a sort of palimpsest; but this is very much a narrative of its own place, culture and period. It is also, importantly, about the world that WhatsApp has built. And so, while it doesn’t try hard to be “topical”, there is this undercurrent, a constant reminder of how social media – used malevolently – moulds us in different contexts.

I caught most of Saharu’s conversation with Akshaya Mukul at The Book Shop a few months ago, and was charmed by his directness and eloquence (he apologised, unnecessarily, for “rambling”). A running theme of the event – including through his banter with the audience – was that he has a very cynical view of human nature, but it wasn’t dark by my standards. And I was glad to hear him say some things you don’t often hear at events where people are trying to be politically correct or “positive” – among them, that for an author it is important to be able to think through the perspective of the *perpetrator* (as opposed to just the victim); that literature has no obligation to address what social scientists want it to address; that in his view people are rarely anti-casteist or anti-racist despite what they profess to be; and that he doesn’t believe literature has conversionary or proselytising power. (“But we just have to give a voice to certain things.”) And a prize quote about the duplicity inherent in human nature: “Any animal that can use speech to express its feelings *will* tell lies.”

I caught most of Saharu’s conversation with Akshaya Mukul at The Book Shop a few months ago, and was charmed by his directness and eloquence (he apologised, unnecessarily, for “rambling”). A running theme of the event – including through his banter with the audience – was that he has a very cynical view of human nature, but it wasn’t dark by my standards. And I was glad to hear him say some things you don’t often hear at events where people are trying to be politically correct or “positive” – among them, that for an author it is important to be able to think through the perspective of the *perpetrator* (as opposed to just the victim); that literature has no obligation to address what social scientists want it to address; that in his view people are rarely anti-casteist or anti-racist despite what they profess to be; and that he doesn’t believe literature has conversionary or proselytising power. (“But we just have to give a voice to certain things.”) And a prize quote about the duplicity inherent in human nature: “Any animal that can use speech to express its feelings *will* tell lies.”All that said, forget about the teller and trust the tale. Do look out for this fine, multi-layered book.

As they lay dying: caregivers and patient in His Three Daughters 17 Oct 2024 6:59 PM (6 months ago)

(my latest Economic Times column)

---------------------- With 20 minutes left in the new film His Three Daughters – a superbly performed chamber drama about three women looking after their dying father in his final days – there is a notable narrative shift. I won’t give away anything important: it’s enough to say that after an hour of storytelling centred on the three daughters, who are negotiating their own complicated interrelationships and personal histories, we meet the father for the first time. Before this he has been a barely glimpsed, immobile presence on a bed in an inside room. Now, as they wheel him into the dining area, he is only half-conscious, only just capable of posing – mechanically, through pain and discomfort – for a selfie with his children; but he is at least a recognisable, flesh-and-blood person.

With 20 minutes left in the new film His Three Daughters – a superbly performed chamber drama about three women looking after their dying father in his final days – there is a notable narrative shift. I won’t give away anything important: it’s enough to say that after an hour of storytelling centred on the three daughters, who are negotiating their own complicated interrelationships and personal histories, we meet the father for the first time. Before this he has been a barely glimpsed, immobile presence on a bed in an inside room. Now, as they wheel him into the dining area, he is only half-conscious, only just capable of posing – mechanically, through pain and discomfort – for a selfie with his children; but he is at least a recognisable, flesh-and-blood person.

And then something else happens that briefly shifts the needle even further from the caregivers to the patient – to his inner life and dazed thoughts, which may have nothing to do with the things his daughters have been preoccupied with for the bulk of the film.

This is one of those risky, tone-altering devices that can take a viewer out of a film. But I think it’s an intentional, carefully thought out rupturing, and it fits a theme that emerged a short while earlier: the unknowability of people, or how a person’s entirety can (perhaps) only be processed through his absence – as opposed to the many disconnected bits you experience at different times and in different contexts while he is alive. Shortly after we see the three daughters trying to find the right words for an obituary, the father stops being an abstraction for us and becomes real. We even get a hint of something about him that the protagonists didn’t know.

In an online session some years ago, a friend and I discussed how illness-centred films are often more about the caregiver than the patient: especially if the latter is in the final stages of terminal illness, unresponsive or catatonic. We spoke about Shoojit Sircar-Juhi Chaturvedi’s October, and about a possible ideological criticism of this generally admired film – that it might be seen as employing the “Women in Refrigerators” trope, where an incapacitated woman becomes a cipher for the playing out of a male character’s personal growth. About other films such as Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers (which His Three Daughters reminded me of). And about how caregiving in general can seem like a self-absorbed, self-congratulatory act even when seriously discharged.

The women in His Three Daughters (one of whom isn’t a biological daughter of the patient) represent different faces of the caregiver: from the ones who worry from a distance, offer financial help and sometimes over-control, to the one who is there round the clock, shouldering most of the burden, knowing things the long-distance progeny can’t know – and who has earned the right to behave erratically once in a while, to seem remote or uncaring. I can relate well to this latter version. During my caregiving years for family members, many dimensions in my personality competed for space on a daily basis: the attentive and the mean-spirited, the vulnerable and the contemptuous. I also saw a great deal of the process through which a once-sentient human being becomes a shell, so that it’s easy to forget that a complex, multi-layered person had inhabited this eroding body and mind: whether it was my grandmother, one of the sharpest people I knew, trying feebly to get things done while confined to bed in her late eighties, or my father – once aggressive and dangerous, now helpless, at the mercy of attendants (and a son who, while discharging his duties, might also on some level have seized his chance to be the bully, taking revenge for earlier times).

I thought of this again while watching that dissonant late scene in His Three Daughters, and it felt vaguely therapeutic: it offered the consoling possibility that in her last days my mother’s mind was somehow in a space free from wracking pain and worry, perhaps turning over memories of remote things that had nothing to do with her immediate situation; things I had never known about and would never know about. Even the most dedicated caregivers, control-freaks as we sometimes are, don’t have to be on top of everything.

I thought of this again while watching that dissonant late scene in His Three Daughters, and it felt vaguely therapeutic: it offered the consoling possibility that in her last days my mother’s mind was somehow in a space free from wracking pain and worry, perhaps turning over memories of remote things that had nothing to do with her immediate situation; things I had never known about and would never know about. Even the most dedicated caregivers, control-freaks as we sometimes are, don’t have to be on top of everything.

Coming of age in the video era: a new book evokes 1980s memories of Newstrack, Lehren and other relics 27 Sep 2024 6:21 PM (6 months ago)

(Wrote this personal essay around a new book for Mint Lounge)

-----------------

On hearing about the recent death of media magnate Nari Hira, I was reminded of the first time I heard that name as a child (briefly thinking it designated a company rather than a person) and of the wave of “video films” that Hira produced in the mid-to-late 1980s. These were quickly made, visually unambitious movies of varying quality that were shot, edited and distributed on video, and heavily promoted in his magazines like Stardust and Society. They didn’t seem to fit any of the usual Hindi-film categories; indeed, one was unsure if they were even “cinema”.  The longest chapter in Ishita Tiwary’s book Video Culture in India: The Analog Era provides some back-story about these films, through a process of discovery by a much younger person who hadn’t lived through the period herself. Tiwary says she had no idea such video films existed, and a few people she spoke to didn’t remember them either – details were slowly uncovered.

The longest chapter in Ishita Tiwary’s book Video Culture in India: The Analog Era provides some back-story about these films, through a process of discovery by a much younger person who hadn’t lived through the period herself. Tiwary says she had no idea such video films existed, and a few people she spoke to didn’t remember them either – details were slowly uncovered.

“It is possible to imagine that the consumption of content in the private space of one's home allowed middle-class women to become the primary spectators of these straight-to-video erotic thrillers,” she proposes. “Video made possible a new imagination of the spectator as not just male.” This might, with hindsight, seem a large claim, given how fleeting the video-film interlude was (and also that satellite TV, with much more permissive content, was just a few years away). Yet, to someone who was a child in 1986-87, it feels plausible. My mother and her friends watched some of Hira's films: I wasn’t allowed to, this being “adult” stuff, franker than mainstream Hindi cinema. But in the whispers around these video films, and in stolen glances at the tape covers, many of us kids saw exotic-seeming names (“Shingora, starring Persis Khambatta”) and heard of such plot points as a woman being involved at separate times with father and son (all this predating the arrival of The Bold and the Beautiful).

More broadly, Tiwary’s book analyses four manifestations of the video culture that changed the viewing experience for us in the early 1980s – making us participants with the illusion of some control over the media we consumed (long before new forms of control and manipulation arose in the internet and smart-phone age). The video film is one of the chapters. The others are the marriage video; the video news magazine (mainly Madhu Trehan’s Newstrack) which offered a different treatment of news compared to the state-run Doordarshan; and video as playing a part in the growth of the Osho Rajneesh cult, presenting the guru as simultaneously an accessible figure and a grand one.

In covering these uses of video technology, the book offers insights into the differences and similarities between video and glamorous big-screen cinema. Tiwary notes the “darshanic” gaze that video films afforded of Rajneesh, contrasting it with visual presentations of movie stars like Vinod Khanna, who was one of his followers. Or how the marriage video, though similar to a home movie, “also had intricate connections with Hindi cinema through its use of film songs and other representational practices”. We see how amateur wedding photographers learnt on the job, through trial and error: how to film a bride as opposed to the groom, family members or guests; how to turn up the glamour quotient with in-camera editing and lighting effects that might seem tacky to us today, but could be very exciting to a middle-class family seeing themselves in a video for the first time. Some videographers even became “directors” during a wedding ceremony, instructing participants to repeat a gesture mid-ritual for the camera. Engaging as all this is, for me the book also provided triggers to video memories that don’t fall directly within the ambit of Tiwary’s study. Though we didn’t have a video player in our own house until I was ten, by the mid-1980s the bulk of my contemporary-film-watching was on cassettes – including pirated ones – rather than in halls. Video may have created a parallel structure to the mainstream Hindi film industry, as Tiwary points out, but for many viewers of the time the lines were very blurred: we watched larger-than-life films like Shahenshah on small screens with animated ads dancing over the action. Even after the advent of satellite TV in our home in early 1992, video played a big role in my viewing – I filled dozens of VHS cassettes with my favourite music videos, old films or TV shows.

Engaging as all this is, for me the book also provided triggers to video memories that don’t fall directly within the ambit of Tiwary’s study. Though we didn’t have a video player in our own house until I was ten, by the mid-1980s the bulk of my contemporary-film-watching was on cassettes – including pirated ones – rather than in halls. Video may have created a parallel structure to the mainstream Hindi film industry, as Tiwary points out, but for many viewers of the time the lines were very blurred: we watched larger-than-life films like Shahenshah on small screens with animated ads dancing over the action. Even after the advent of satellite TV in our home in early 1992, video played a big role in my viewing – I filled dozens of VHS cassettes with my favourite music videos, old films or TV shows.

Which means I relate to Tiwary’s point about video combining an immaterial experience with a material or physical one. The process of keeping one’s finger poised above the “Record” button, waiting to press it at just the right moment – and capture the opening seconds of a much-sought-after music video that was likely to play next on a countdown show – was thrilling; it conferred a sense of Godlike power and agency that earlier generations of viewers didn’t have. This was equally true about fast-forwarding a song while watching a film, or setting the timer recording for a TV programme (while keeping one’s fingers crossed that the power wouldn’t go). Or there was the commingled dismay and hope of lifting a cassette flap and blowing at real or imagined dust on the film, to remove “snow”. Tiwary also mentions the story (which came to her second-hand, but which we denizens of that time remember well) about the infamous interrogation scene from Basic Instinct – the uncrossing of Sharon Stone’s legs – becoming worn out on cassettes as viewers rewound, paused and replayed it.  Other things covered here touched a chord too: memories of the video magazine Lehren, a filmic version of gossip magazines, which introduced us to the behind-the-scenes of movie production, including cheap-looking “mahurat” shots. Or Newstrack’s coverage of the anti-Mandal Commission protests, with its reminder of a nasty moment where police callously picked up and manhandled an injured young man lying on the road – and of my mother and aunt watching the screen and expressing indignation at this visual, all of us becoming briefly politicised by the starkness and immediacy of the footage.

Other things covered here touched a chord too: memories of the video magazine Lehren, a filmic version of gossip magazines, which introduced us to the behind-the-scenes of movie production, including cheap-looking “mahurat” shots. Or Newstrack’s coverage of the anti-Mandal Commission protests, with its reminder of a nasty moment where police callously picked up and manhandled an injured young man lying on the road – and of my mother and aunt watching the screen and expressing indignation at this visual, all of us becoming briefly politicised by the starkness and immediacy of the footage.

Video Culture in India is more accessible than many other academic books, largely shorn of the echo-chamber jargon and repetitiveness that makes many such publications a slog. It could have been much better copy-edited, and there is an occasional randomness in its linking of different video cultures. But the book is valuable as both a chronicle of a particular, evanescent moment in India’s visual-media culture and as a memory-reviver for my generation, growing up in that narrow band of time between the 1970s – when films could only be seen in cinema halls – and the early 1990s, when it first began to feel like you never had to step out of the house at all.

A discussion around political/paranoia thrillers 27 Sep 2024 3:53 AM (6 months ago)

My online film group is conducting a Zoom discussion around political/paranoia thrillers on the evening of Friday, Oct 4. Please mark the date and drop in if you’re free and willing.

We will be broadly looking at films centred on political assassinations/attempted assassinations/cover-ups/conspiracies. The starting point for the discussion will be Costa-Gavras’s Z and Dibakar Banerjee’s Shanghai, which are adapted from the same source text – but we will also touch on a number of other films, including some key American political thrillers of the 1960s and 1970s. Among them: The Parallax View, The Manchurian Candidate, Winter Kills, Executive Action, Seven Days in May, JFK.

I have sent downloadable film links to my email group – if anyone else wants to be on the mailing list, please mail me (jaiarjun@gmail.com) or leave your ID in the comments here.

A note on Rahul Bhatia's The Identity Project 18 Sep 2024 1:14 AM (7 months ago)

The photos here are of author Rahul Bhatia, human-rights activist Usha Ramanathan, and Nisar Ahmad (tireless striver for justice after losing his home in the 2020 Delhi riots) during a very thoughtful conversation last evening, around Rahul’s new book The Identity Project: The Unmaking of a Democracy. This is a wide-ranging work – journalism and narrative non-fiction – about the development of India’s enormous biometric identification project, and how it has intersected with the growth of Hindutva/militant and exclusionary Hinduism over the past three-and-a-half decades.

It took me just two days to read The Identity Project, which was very unusual because my (non-work-related) reading has been almost non-existent in recent times. But this is a testament to the directness and gentleness of Rahul’s writing, qualities I have been familiar with ever since we became acquainted 20 years ago (even back then, when so many of us were trying to be “writerly” to impress – first on blogs, later when opportunities for long-form feature writing opened up – there was an immediacy about his work that was enviable). I began reading the book mainly to revisit and more fully understand those chaotic months in 2019-2020 when the anti-CAA/NRC protests were followed by the anti-Muslim riots in north-east Delhi (and all of it was soon overshadowed in many of our minds by the pandemic and the lockdowns); but I just went on reading, as the narrative moved back and forth in time – from Dayanand Saraswati and the Arya Samaj 150 years ago to LK Advani’s rath yatra to contemporary times where men like Nisar (a protagonist and guiding light in the book) found their family’s lives threatened by long-time neighbours, including men he had seen since they were children. The historical back-story in the second section was particularly important for me since I knew very little about figures like Balakrishna Shivram Moonje (whose life, I realise with some interest, ran almost exactly parallel to Mahatma Gandhi’s – 1872 to 1948. His idea of Hinduism, and ultimately of India, was very different from Gandhi’s, though).

In between all this, there are terrific pen portraits of Nandan Nilekani, Advani’s personal aide Deepak Chopra, and others. And a sinisterly entertaining passage where Rahul visits a shakha and briefly becomes a sort-of honorary RSS member himself – the bits here about a game called “Mantriji” reminded me of the whistle-blower accounts of Ku Klux Klan meetings, about grown men playing childlike games, having fun with code-words and phrases, while also posturing and nursing their grievances.

In between all this, there are terrific pen portraits of Nandan Nilekani, Advani’s personal aide Deepak Chopra, and others. And a sinisterly entertaining passage where Rahul visits a shakha and briefly becomes a sort-of honorary RSS member himself – the bits here about a game called “Mantriji” reminded me of the whistle-blower accounts of Ku Klux Klan meetings, about grown men playing childlike games, having fun with code-words and phrases, while also posturing and nursing their grievances.All this means the book is structurally complex – having many balls in the air – but it stays lucid all the way through because the writing flows so easily. Do look out for it, and for other conversations around it.

Bees saal baad 16 Sep 2024 12:31 AM (7 months ago)

This blog turned 20 years old a couple of weeks ago. (*Cliche alert* Very strange to think about this - it feels like yesterday that I started writing a few scattered posts with no clear sense that it could lead to anything, or that it would play such a big role in my life as a writer.)

Seasons in the sun: how an Anglophone boy failed to engage with (or misheard) Hindi song lyrics 29 Aug 2024 12:13 AM (7 months ago)

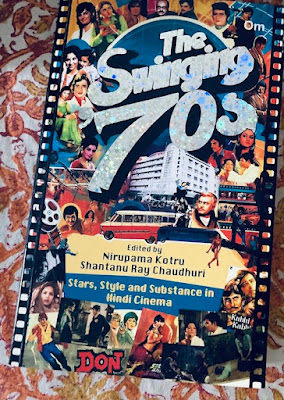

(My latest Economic Times column. It also mentions the bulky new anthology The Swinging Seventies – co-edited by Nirupama Kotru and Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri – which has had many promotional events over the past few months. I have been involved with quite a few of them, mainly in Delhi but also elsewhere. Please look out for the book)

---------------------

Last month, in Bombay, I participated in a few cinema-related panel discussions featuring a number of writers, critics and filmmakers. There was a conversation with director Vishal Bhardwaj and the talented young actress Wamiqa Gabbi about their Khufiya, a spy thriller that in the typical Bhardwaj style also manages to be an unusual love story and a wacky dark comedy. There were also a few discussions around the anthology The Swinging Seventies, a collection of essays about 1970s Hindi cinema.

All this was fun, given the inevitable constraints of a 40-minute session where five or six movie-nerds must condense their thoughts. There was camaraderie, over-the-top fandom, and unexpected links were made. During a tribute to Shyam Benegal, while speaking about a cherished Benegal film Charandas Chor, I took the opportunity to tell fellow panellist Ketan Mehta that his debut feature Bhavani Bhavai was one of my favourite films – artfully melding cinema with folk theatre in much the same way that Charandas Chor did. But there was one session where I felt like an impostor – or at least that I should stay quiet and listen to what other, wiser souls had to say. This was a talk about lyrics in our film songs.

But there was one session where I felt like an impostor – or at least that I should stay quiet and listen to what other, wiser souls had to say. This was a talk about lyrics in our film songs.

Ironically my own piece in the 1970s book had centred on a song – “O Saathi Re” from Muqaddar ka Sikander – which I loved so much as a child that I tried to record myself singing it (before sadly conceding that posterity would be better served by the Kishore Kumar version). But speaking generally, much as I loved film songs while growing up, my engagement with them was more at the level of tune than lyrics. The music would often embed itself into my head even though I hadn’t quite registered the words.

I could, of course, understand an old song with the surface simplicity of, say, “Mera joota hai Japani” or “Nanhe munne bachhe”– and closer to my own time, I loved the lowbrow wordplay of the Tom and Jerry song in Sharaabi (“Khel rahe thay danda gilli / Chooha aage, peechhe billi”), or lyrics that were accessible and integral to a narrative situation, e.g. “Chal mere bhai” from Naseeb. But even today, I can say little of worth about the differences in meter and philosophy in the poetry of, say, Sahir Ludhianvi and Majrooh Sultanpuri. Loving masala Hindi cinema – with its dialogue-baazi and dhishoom-dhishoom – was one thing, but it was quite another to process Hindustani or Urdu phrases of a certain complexity or literariness.

I don’t know if this is a left brain-right brain thing, or something that can be explained by the fact that I grew up in an Anglophone environment, with English as a first language. (Later, in my teens, encountering English lyrics by Dylan or Cohen or even Eminem, I memorised the words of entire songs without even consciously trying.) Or it could be because mainstream Hindi film songs of the 1980s tended to be lyrically formulaic, with endless permutations of “pyaar”, “ikraar”, “deewana” and “parwaana” – and this encouraged laziness as a viewer. As a child I loved romantic songs from films like Love Story, Betaab, Hero, Pyaar Jhukta Nahin and Ek Duuje ke Liye, but then a line like “Yaad aa rahi hai / teri yaad aa rahi hai / yaad aane se, tere jaane se / Jaan jaa rahi hai…” couldn’t be accused of lyrical ambitiousness, whatever else it was. Years later, listening to something like the catchy Govinda-Neelam song “Pehle pehle pyaar ki” from Ilzaam, it was impossible to miss the parts where they went “Pyaar! Pyaar! Pyaar!” in a growing crescendo – but that didn’t require intense concentration on my part.

One offshoot of this was the comedy of misheard lyrics when it came to “deeper” songs. For instance, I spent years wondering why Amol Palekar in “Ek akela iss shahar mein” was always searching for Sabudana, and it came as a relief to learn that other friends had made this mistake too – Gulzar’s “aab-o-daana” being too high-flown for us youngsters. But there is one blooper that’s uniquely my own. It involved a song from the film Sindoor, where Jaya Prada lists the seasons thus: “Patjhad, Saawan, Basant, Bahaar”. The first of those words was so indecipherable for me that I made no effort to understand the meaning of the line – and then, as an insular South Delhi kid, figured that the last two words were “Vasant Vihar”. For a few days I felt a strange pride that a Bombay movie had acknowledged a posh Delhi colony in this timeless way.

Naturally, this was a disclosure I avoided making in the discussion last month, in the presence of Vishal Bhardwaj and many other maestros of song.

------------------------------------

(And a couple of other photos from the sessions, here)

|

| Khufiya session with Shantanu, Govardhan Gabbi, Wamiqa Gabbi and Vishal Bhardwaj |

|