A long strange trip 1 Sep 2024 9:09 AM (7 months ago)

For readers who don’t already know this, my new blog is over at Substack:

scottsumner.substack.com

This will be my final Money Illusion post. The blog began on February 2, 2009. But the events that led to the blog took place in late 2008. Indeed my life can be divided into two segments, before and after September 16, 2008. It was that specific Fed meeting that radicalized me, and which led me to create this blog.

Originally, I planned to go back and review my first few posts, to see how they compare to my current views. I’ve decided to do that on September 16th, over at my new blog. That’s the 16th anniversary of a Fed meeting that Ben Bernanke later described (in his memoir) as a mistake:

At the end of the discussion we modified our planned statement to note market developments but also agreed, unanimously, to leave the federal funds rate unchanged at 2 percent.

In retrospect, that decision was certainly a mistake. Part of the reason for our choice was lack of time—lack of time in the meeting itself, and insufficient time to judge the effects of Lehman’s collapse.

I’m not going to thank all the people that helped me along the way, as I’m so forgetful I’d leave out lots of names. The general categories include the other market monetarists, other bloggers, my commenters, my colleagues at Bentley, and my wife and daughter (who had to sacrifice when I devoted too much time to blogging.)

Special thanks to Joe Weisenthal, Derek Thompson, Matt Yglesias and of course Tyler Cowen, who made September 13, 2012 the high point of my life, at least from a career perspective. And yes, the praise was excessive. (Today, that era seems a bit unreal, like another life.)

And thank God we market monetarists were able to come out ahead in our debate with the Keynesians, who predicted that (due to fiscal austerity) spending would slow sharply in 2013. It accelerated.

I also have regrets; most notably that the blog’s tone has often been too critical of people with whom I disagree, including other bloggers and policymakers like Ben Bernanke.

This blog has obviously deteriorated over time. That’s partly because the world situation has become fairly bleak. My whole adult life, I’ve strongly opposed the twin evils of socialism and nationalism. Unfortunately, the world has seen a modest resurgence in socialism and a big increase in nationalism over the past 15 years. This may have contributed to my more pessimistic tone. Burn out. Note that in some of my early posts, I pointed to the fact that previous NGDP collapses such as 1929-33 had also had this effect.

In my new blog, I hope to make the tone more upbeat and I will try hard to improve the quality. I hope to see you all there.

Magic dust (a fable) 1 Sep 2024 9:08 AM (7 months ago)

In the mid-1990s, the consensus view was that central banks should target inflation at 2%. Then in the late 1990s, a light rain of “magic dust” descended on the islands of Japan. The dust made people passive and fatalistic, and the economists there suddenly forgot how to create inflation, a previously inconceivable development.

At the time, Western economists were stunned. “What’s wrong with the Japanese? Why don’t they just do X, Y and Z?”

A decade later, the same magic dust fell on North America and Europe (fortunately the southern hemisphere was spared.) Now Western economists forgot how to create inflation. They began to claim that it was impossible when interest rates were zero.

A few lonely economists had a genetic mutation that made them immune to the effects of the magic dust. They wondered why economists had changed their minds about the efficacy of monetary policy. After all, the Fed and ECB had also failed to do X, Y and Z.

Another decade went by, and the effects of the magic dust began to wear off. The next time deflation threatened in an environment of zero rates, central banks began doing some of the X, Y, and Z that they had recommended to the Japanese a few decades earlier, And it quickly created lots of inflation.

Are we moving toward fiscal dominance? 31 Aug 2024 3:04 PM (7 months ago)

A recent Bloomberg article suggested that we may be moving toward a regime characterized by fiscal dominance, at least part of the time:

In their paper, three economists from New York University, Stanford and London Business School argue that the US is moving from a regime of “monetary dominance” to one of “fiscal dominance.” In the former, the Fed controls inflation by adjusting short-term nominal interest rates. The government supports these efforts by committing to increase future taxes, ensuring that other interest rates don’t change too much and debt doesn’t overwhelm markets. Under a monetary dominance regime, interest rates and inflation are low and relatively stable.

I don’t agree with the claim that monetary dominance implies low and stable interest rates or inflation. We clearly had monetary dominance in the 1960s and 1970s, when budget deficits were small as a share of GDP. And yet inflation was high and unstable. Both in the Great Inflation, and in the more recent bout of high inflation, the problem was the Fed’s misguided belief that easy money is a good way to create jobs.

The regime changed during and after the pandemic, when wartime-sized debt was issued with no care of paying it back. . . . Under such a [fiscal-dominance] regime, the Fed is less powerful.

I wouldn’t say the Fed “manages” bouts of inflation, as that term makes them seem like an innocent bystander. The Fed created the high inflation of 2021-22 with a highly expansionary monetary policy. And the Fed was no less powerful than before, as it had plenty of “ammunition” to adopt a tighter monetary policy if it had wished to.

Not only is its job harder, but its tools are less powerful — it has less influence over interest rates.

Its power doesn’t come from control of interest rates; it comes from control over the gap between the target rate and the natural rate. And it has just as much power over that gap as before deficits became large.

After spending moderated and monetary policy became more restrictive, the US returned to a monetary policy regime. But the nation’s debt trajectory risks a future turn to fiscal dominance.

It moderated only relative to the Covid period. In absolute terms, fiscal policy is currently highly irresponsible, especially if compared to the Great Inflation of 1966-81. If the fiscal dominance model were true, the US would currently be experiencing very high inflation. On the other hand, I agree that our current path does impose at least some risk of slipping into fiscal dominance. That’s what tends to happen in banana republics.

Fiscal policy, which has become more ambitious in recent years, is finally doing the job it’s supposed to do. Both parties have been vocal in supporting policies that aim to shift production from services to manufacturing, either through tariffs or with industrial policy. There are also goals related to improving infrastructure, lowering the cost of housing, and reforming the immigration system. These policies change the supply side of the economy . . .

In a recent Econlog post, I pointed out that tariffs might end up shifting output toward services, by increasing the relative price of manufactured goods. (Tariffs might reduce the trade deficit, but probably won’t.) And those three goals sound fine, but I don’t see much action.

An American economic miracle? 30 Aug 2024 8:14 AM (7 months ago)

Matt Yglesias directed me to this tweet:

If you looked at certain polls, you’d think the economy was doing poorly. On the other hand, if you looked at state economic performance polls, or polls asking about an individual’s personal financial situation, then things look far better. But one thing is clear—the US is outperforming the economies of other developed countries by a fairly wide margin. Why is that?

Let’s start with the macro. I think Pethokoukis somewhat overstates the supply shock and monetary headwinds. As you know, interest rates don’t matter. The thing that does matter (NGDP) has been a headwind, not a tailwind:

The growth rate has recently slowed, but remains well above the pre-Covid norm.

There were some supply shocks in 2022, but the energy situation is now pretty good, and many other supply line bottlenecks have been resolved. On the plus side, a big surge in immigration has added substantial labor force supply (even with the recent downward revision.)

At the micro level:

1. We have less regulation in some key industries like fracking, and this has boosted our GDP relative to Europe.

2. We have gains from agglomeration and network effects. When combined with an inflow of many highly talented individuals, this has led us to vastly outperform our rivals in high tech.

3. We have our Nimby problems, but in much of America it’s still pretty easy to build. Densely populated Japan and Europe (especially the UK) probably have more restrictions on building.

Note that all three of these micro factors are things that have become much more important over the past 10 or 20 years. And this roughly corresponds to the period when Europe stopped catching up to us and began falling further behind.

Jeffrey Ding on China 30 Aug 2024 8:14 AM (7 months ago)

I’ve been amazed by the response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The most militarily expansionist leader since Hitler and Stalin starts a war that threatens to spiral out of control. He leads a country with enough weapons to destroy most of the US population. He threatens to use nuclear weapons (and is scolded by China for doing so.) And in response we are told by our foreign policy establishment that “China is the real threat”.

A recent podcast provides some interesting historical parallels:

Jordan Schneider: Then in the 1980s, the concern was that Japan would overtake the US. David Halberstam — author of The Best and Brightest and Breaks of the Game — wrote in 1983 that Japan’s industrial ascent was America’s most difficult challenge for the rest of the century and a “more intense competition than the previous political-military competition with the Soviet Union.”

There was a deep consensus within the American body politic that America was losing the technological future and long-term productivity race to Japan. What didn’t Japan get right?

Jeffrey Ding: This was a very real threat in the eyes of the US. Henry Kissinger wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post saying that Japan’s economic strength and rise in high-tech sectors would eventually convert into military power and threaten the US. A poll in the late 1980s found that more Americans were worried about Japan than the Soviet threat to US national security.

The trend that I see so clearly with all these historical examples is the US overhyping other countries’ scientific and technological capabilities. One reason we do that is because we don’t pay as much attention to diffusion capacity.

Japan was the real threat, not the Soviet Union?? Americans seem to have a deep-seated need to see Asians as the “real threat”, not Europeans. Recall the ethnic group that FDR put in concentration camps back in 1942.

Later, Ding points out that it’s not easy to determine what strategy toward China is best, even if we accept the premise that it is a threat:

Jeffrey Ding: We have shifted so far in the direction of US national security interests and the need to beat China in all these different forms of competition. The biggest risk is if China overtakes us on something, whether militarily, economically, or by soft power.

I’m not sure where I stand on this, but why are we not considering that the biggest national security risk for the US is a weak China and a China that can’t sustain its growth? For the longest time that was US State Department policy. A strong China is good for peace.

All this self-flagellation that’s been coming out in terms of China’s AI sector has been overhyped. China could also suffer economic stagnation. What would the national security consequences be for the US? They might not be good.

It’s not even in the Overton window. We’re not even talking about it anymore in Washington.

To be clear, both Schneider and Ding see China as a serious threat. Please read the entire interview. But at least they seem to have some historical perspective that is lacking in most other commentary on the issue.

Yglesias on political sorting 30 Aug 2024 8:13 AM (7 months ago)

There has recently been a lot of discussion about how all of the conspiracy nuts are moving over to the GOP, whereas not so long ago they were at least as common among Democrats. Matt Yglesias has a very good post that points out how this is a problem for both sides.

The TLDR is that Republicans increasing suffer from a lack of people with the knowledge required to craft good public policy, and the Dems suffer from an epistemic monoculture with no dissenting views. Here are a few excerpts:

Similarly, I think policy-relevant research done in economics departments is a lot more useful and credible than other forms of social science, not because economists are so great but because an economics paper is much more likely to clear the “has at least one conservative read this?” test.

For reasons that sociologists, anthropologists, and social psychologists are probably better-situation to explain, if you work in an environment where all your colleagues and peer reviewers and people you talk things over with in a seminar are left-wing, you are going to get biased results. Again, not necessarily because anyone is trying to bias the results, but because each individual person has their own biases and when almost all of those biases are mutually reenforcing, you get a bad outcome. . . .

The basic problem is that just saying government programs should help address problems that aren’t addressed by the market alone, while true, offers basically no guidance about what to actually do. It is very, very important to come up with correct empirical analysis or else you’re not going to accomplish anything.

Yglesias uses this analysis to explain how the public health establishment screwed up during Covid.

The GOP has a different set of problems:

Are conservatives succeeding in building compelling institutions that can address their concerns about trends in American life? I think they pretty clearly are not, even according to conservatives. And on a policy level, they are completely up the creek without a paddle.

The pandemic revealed that many longstanding conservative criticisms of the drug approval process have some merit.

But there is no post-pandemic FDA reform push from the GOP, and certainly no agenda to take lessons learned from Operation Warp Speed and apply them to other issues. Republicans have become the party of conspiracy theorists who believe Bill Gates is using vaccines as a covert mind control program, so even when they hit on something that works, they don’t dare talk about it or build compelling narratives around it.

Read the whole thing.

Tyler Cowen has recently talked about how you need serious expertise to do effective deregulation. With the GOP well on the way to kicking all intellectuals out of the party, where will it find that expertise? Read some of JD Vance’s comments on economic policy, and just imagine him being put in charge. (Yeah, I know—the Dems. But doesn’t a country need at least one party that understands economics?)

Reason magazine has a very good article on how Trumpistas are jockeying for position in the next administration:

“A red flag went up if a prospective employee answered ‘deregulation and judges’ when asked to name their favorite Trump policies,” Swan wrote, also in 2022. “It was a sure sign the applicant could be a weak-kneed member of the establishment.”

But the solution to Trump’s first problem—ensuring his new staff is fully ideologically aligned with him—pulls against the solution to his second. He can have people who are true believers or he can have people who are competent; he probably can’t have both, because there are simply too few of them. . . .

“The best way to describe these lists is it looks like they’re looking for incompetence as the chief qualification,” says Cato Institute Senior Fellow Thomas Firey. “The bureaucracy, whether you love it or hate it, is an extremely complex machine that is extremely hard to operate….It’s like giving my 8-year-old the keys to a steam shovel. Nothing’s going to happen but a disaster.” . . .

Yes, a whole brood of groups, new and old, have positioned themselves to help a second Trump administration do better. But there are reasons to be skeptical that they’re up to the task. Behind the scenes, the various organizations are busy squabbling among themselves and jockeying for prominence. And several of them are gimcrack enterprises headed up by 20-somethings whose biggest claim to fame is acting out online via inflammatory social media posts.

Eh, what could go wrong? Read the whole thing.

PS. Razib Khan has a tweet showing that in per capita terms his blog has a much bigger audience in New York than Texas, and a much bigger audience in Washington than Florida. Even conservative bloggers are much more widely read in liberal states.

PPS. Watch this 60 seconds, and then extrapolate another 4 years of increasing senility. I’m going to have so much fun. Future historians will call this the era of senile old men.

The final nail for fiscal dominance? 27 Aug 2024 10:48 AM (7 months ago)

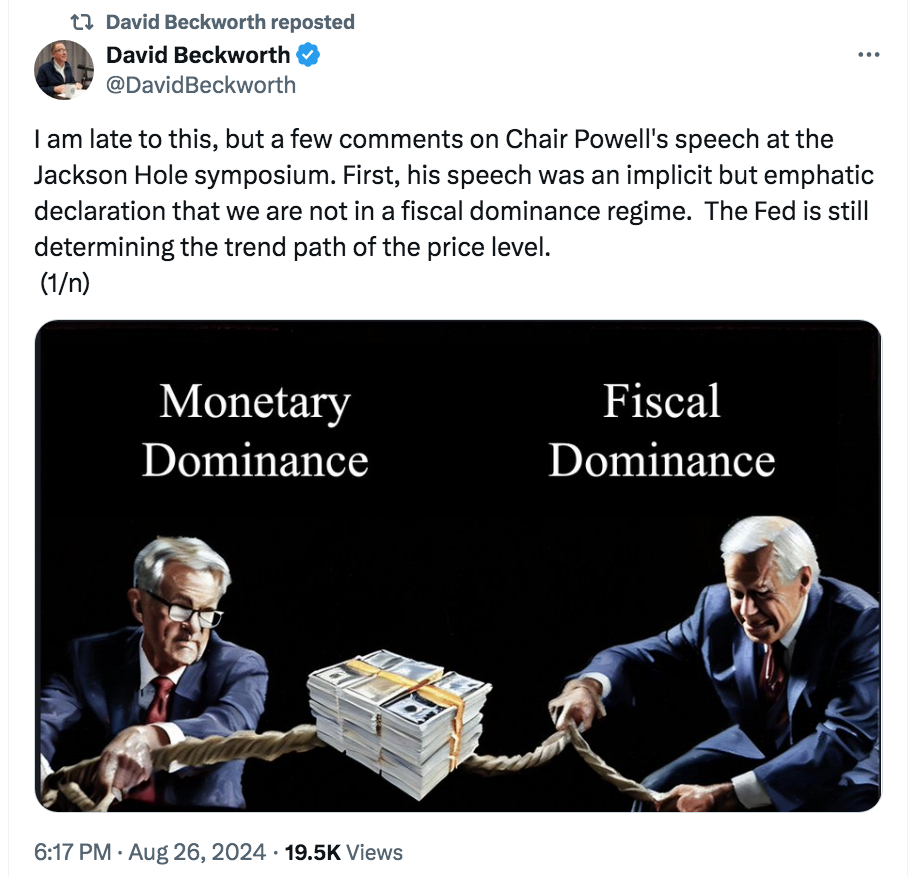

One of my biggest frustrations over the past 15 years has been the economics profession’s drift away from certain well established propositions, such as the fact that the Fed controls the price level. But there are signs of light. David Beckworth has a twitter thread discussing how inflation has recently fallen sharply despite absurdly large budget deficits as far as the eye can see:

Ironically, our biggest inflation episode (1966-81) occurred during a period of relatively small budget deficits. The gross federal debt ratio fell from 40% of GDP in 1966 to 31% of GDP in 1981. Today, it’s over 120% of GDP and likely to rise much higher.

Read Beckworth’s entire thread.

Fifty to one on job growth? 27 Aug 2024 10:47 AM (7 months ago)

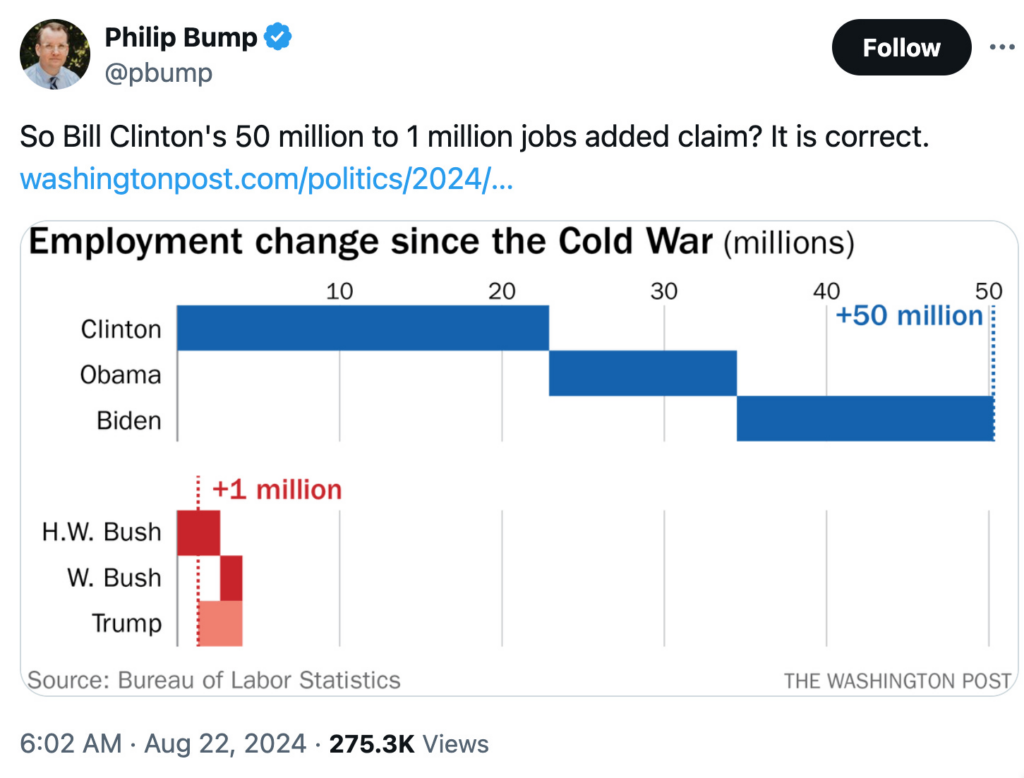

Brad DeLong directed me to a tweet that contained this intriguing graph:

If you polled 51 million Americans and found that 50 million supported X, whereas 1 million opposed X, that would be a highly significant survey. So what should we make of the fact that over the past 35 years, Democratic presidents have “created” (been associated with) 50 million net new jobs and GOP presidents have been associated with 1 million net new jobs? Isn’t 51 million a statistically significant sample size?

Of course what’s really going on here is that we have only 6 observations, six administrations. Is it unusual that the three Democratic administrations were associated with fast job growth, or just luck? That’s actually not an easy question to answer. It’s at least partly luck, as no one seriously believes that the poor Trump performance is due to anything other than being in office when Covid hit. (Trump did mishandle Covid in some respects, but that wasn’t the deciding factor. Even though I’m a Trump hater, I don’t blame him for the poor jobs numbers or the poor crime statistics when he was in office)

If I were a Democratic partisan, I’d make a different argument. Ten of the past eleven recessions (since 1952) have occurred under GOP presidents. I mention this because the graph above is largely explained by the fact that each GOP president happened to finish his term in office during a recession or the early stages of recovery. It’s a business cycle issue. Republicans have been either very unlucky, or have been less adept at macroeconomic stabilization policy than Democrats.

So is this 10-1 ratio statistically significant? That’s not really the right way to think about these things. We wouldn’t be discussing the issue at all unless the ratio looked odd. We select usual patterns when deciding what to write blog posts on. A better approach would be to ask if there are policy differences between the GOP and the Democrats that can explain this pattern.

I imagine no one will like this answer, but I suspect that the 10-1 ratio is largely but not totally random. During much of this period, the GOP had more of an anti-inflation bias, whereas the Dems had more of a pro-jobs bias. As a result, some of the GOP recessions were plausibly caused by earlier Democratic over-stimulus. But not all. I’d say 1970 and 1981 are the two clearest cases of recessions that occurred under GOP presidents that were caused by previous Democratic over-stimulus. Maybe 1953, but that was probably more of a post-Korea War thing.

So the GOP is probably not as bad as the 10-1 ratio would suggest. Even so, there are some other data points that are hard to explain away. Why did Eisenhower have 3 recessions? Again, all of the Democratic presidents since 1952 have only generated one recession (in 1980.) And that was the mildest of the 11 recessions.

To summarize, the 50 million to 1 million ratio is a great talking point for Dems, but largely coincidence. On the other hand, a careful look at the factors causing recessions suggests that the Dems might really have been somewhat better on the jobs front.

Of course today’s GOP is nothing like the Eisenhower GOP. In addition, the Fed has gotten gradually better in lengthening the business cycle. I strongly doubt that we will see 3 recessions in the next 8 years, regardless of which party is in power.

PS. Don’t take this post as me dumping on Eisenhower, who was vastly better than recent GOP presidents.

Hanania on the GOP 27 Aug 2024 10:47 AM (7 months ago)

Here’s Richard Hanania:

We can already see Republican candidates and institutions shifting over to Gribble messaging. The Heritage Foundation, once believed to represent elite conservative thought, goes to Twitter and implies that the Secret Service tried to assassinate Trump. JD Vance has praised Alex Jones as a truth teller. Meanwhile, Ted Cruz and Vivek Ramaswamy went around earlier this year predicting that the Democrats would make Michelle Obama their presidential nominee. Recall that Trump’s original rise to prominence within Republican politics was through his embrace of Birtherism. . . .

I’ve always said that if Trump loses this election, he’s got a very good chance of being the 2028 Republican nominee. But if he’s not in the running for whatever reason, then the Gribbles will be up for grabs. They won’t get anywhere in a Democratic primary given that the party is now composed of more educated and high trust voters. But on the Republican side, a candidate who consolidates Joe Rogan and Tucker types can be a force in a divided primary where it may take no more than a third of the vote to win. He may not be a conventional conservative, but it would be fitting if the Trump era culminated in Republicans becoming more moderate on policy while getting crazier and more paranoid.

Could this figure be RFK himself? Note that the Low Human Capital types who make up the Republican base love celebrities. There’s a reason that some conservative papers that sometimes do serious journalism like The Daily Mail and The New York Post double as gossip mags. The Kennedy family itself has a large role to play in QAnon cosmology. RFK has a history of holding liberal positions, but Trump showed that one can easily flip-flop, and even if you don’t, Republican voters can be very forgiving if you’re a celebrity who hates elites enough and endorses conspiracy theories. Kennedy has already started walking back some of his prior beliefs, like his previous views on gun control, that would be unpalatable to a conservative electorate.

I doubt that either Trump or Kennedy will be the 2028 nominee (partly because I expect Trump to win in 2024.) But Hanania’s entire post is well worth reading, if you like politics. Or should I say if you hate politics? And when you think about it, is there any difference?

The TLDR is “Yeah, we’re definitely a banana republic.”

PS. NYT headline of the day: “Trump Can Win on Character”

Bayesian analysis 25 Aug 2024 2:09 PM (7 months ago)

The FT has a good article that might be seen as being tangentially related to my earlier post on lab leak vs. zoonosis:

If a screenwriter were to come up with a storyline in which a tech tycoon drowns when his luxury yacht is hit by a freak storm just two days after his co-defendant in a multibillion dollar fraud trial — for which both men were recently acquitted — is fatally hit by a car in another set of ostensibly unsuspicious circumstances, they might very well be told this was rather too implausible for viewers to buy.

And yet this was the tragic real-life series of events over the past week or so. . . .

It didn’t take long for the conspiracy theories to start. Pro-Russia personality Chay Bowes posted on X a clip of himself speaking on the Russian state-owned RT channel in which he pointed out the low probability of being acquitted in a federal criminal trial in the US — about 0.4 per cent, according to Pew. “How could two of the statistically most charmed men alive both meet tragic ends within days of each other in the most improbable ways?” asked Bowes.

The article also mentioned that back in 2009, two identical numbers came up back to back in Bulgaria’s national lottery, at odds of four million to one.

PS. The name of Mike Lynch’s yacht? Bayesian.

No, I’m not making that up.