The Family Home: From Shelter to Asset to Liability 18 Apr 9:41 AM (15 hours ago)

The deflation of asset bubbles and higher costs are foreseeable, but the magnitude of each is unpredictable.

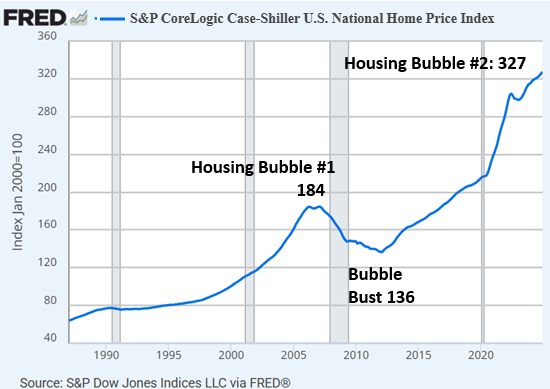

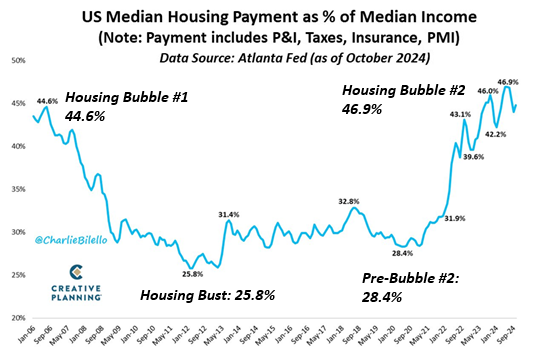

With the rise of financialized asset bubbles as the source of our "growth," family home went from shelter to speculative asset. This transition accelerated as financialization (turning everything into a financial commodity to be leveraged and sold globally for a quick profit) spread into the once-staid housing sector in the early 2000s. (See chart of housing bubbles #1 and #2 below).

Where buying a home once meant putting down roots and insuring a stable cost of shelter, housing became a speculative asset to be snapped up and sold as prices soared.

The short-term vacation rental (STVR) boom added fuel to the speculative fire over the past decade as huge profits could be generated by assembling an STVR mini-empire of single-family homes that were now rented to tourists.

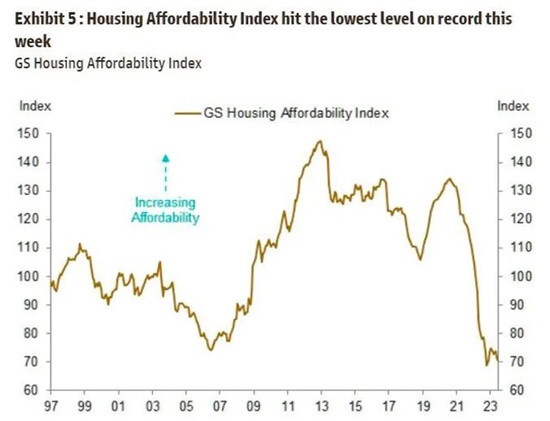

Now that housing has become unaffordable to the majority and the costs of ownership are stair-stepping higher, housing has become a liability. I covered the increases in costs of ownership in The Cost of Owning a Home Is Soaring 11/11/24). Articles like this one are increasingly common:

'I feel trapped': how home ownership has become a nightmare for many Americans: Scores in the US say they're grappling with raised mortgage and loan interest rates and exploding insurance premiums.

The sums of money now required to own, insure and maintain a house are eye-watering. Annual home insurance for many is now a five-figure sum; property taxes in many states is also a five-figure sum. As for maintenance, as I discussed in

This Nails It: The Doom Loop of Housing Construction Quality, the decline in quality of housing and the rising costs of repair make buying a house a potentially unaffordable venture should repairs costing tens of thousands of dollars become necessary.

Major repairs can now cost what previous generations paid for an entire house, and no, this isn't just inflation; it's the result of the decline of quality across the board and the gutting of labor skills to cut costs.

Here's the Case-Shiller Index of national housing prices. Housing Bubble #2 far exceeds the extremes of unaffordability reached in Housing Bubble #1:

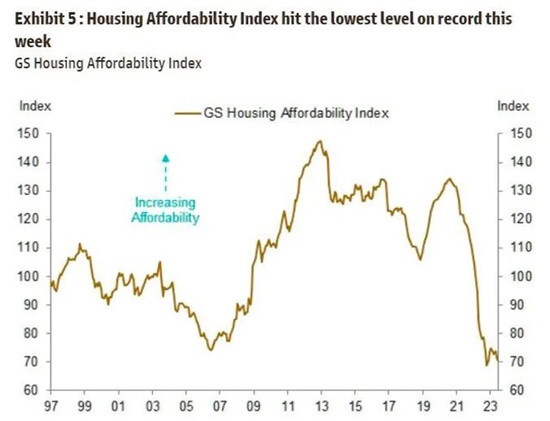

Here's a snapshot of housing affordability: buying a house is now an unattainable luxury for those without top 20% incomes and help from parents.

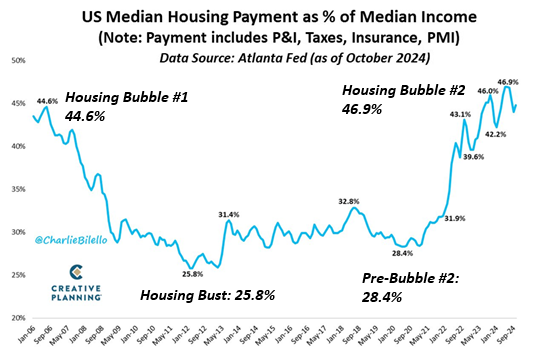

The monthly payments as a percentage of income are at historic highs:

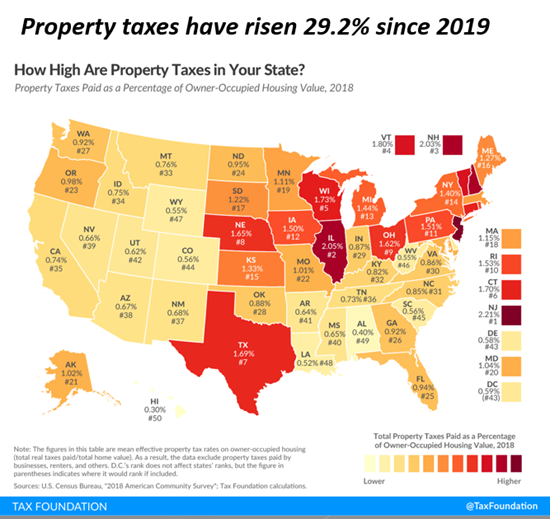

Property taxes are rising in many locales as valuations bubble higher and local governments seek sources of stable revenues:

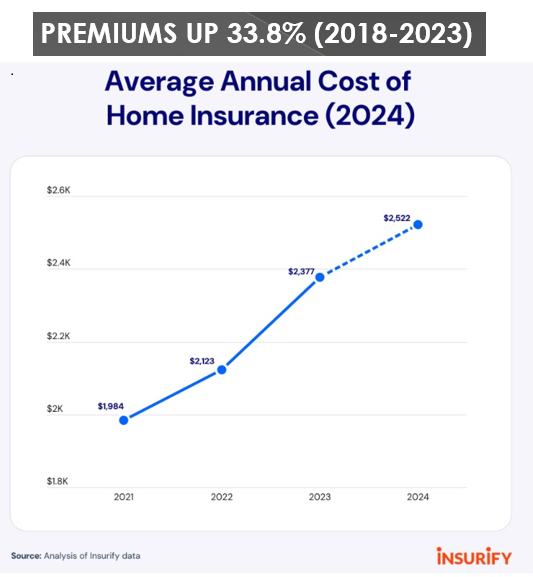

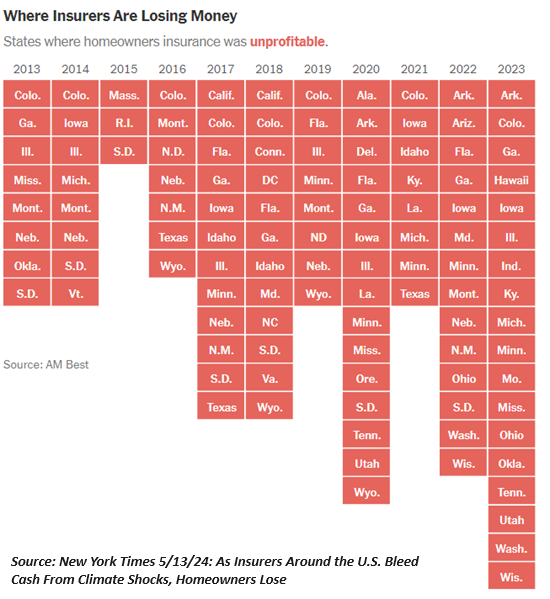

Home insurance costs vary widely, but all are skewing to the upside.

As I often note, the insurance industry is not a charity, and to maintain profits as payouts for losses explode higher, rates have to climb for everyone--and more for those in regions that are now viewed as high-risk due to massive losses in fires, hurricanes, wind storms, flooding, etc.

All credit-asset bubbles pop, and that inevitable deflation of home valuations will take away the speculative punchbowl. What's left are the costs of ownership. As these rise, they offset the rich capital gains that home owners have been counting on for decades to make ownership a worthwhile, low-risk investment.

The deflation of asset bubbles and higher costs are foreseeable, but the magnitude of each is unpredictable. The ideas that have taken hold in the 21st century--that owning a house is a wellspring of future wealth, and everything is now a throwaway destined for the landfill--are based on faulty assumptions, assumptions that have set a banquet of consequences few will find palatable.

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Roger H. ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Jackson T. ($7/month), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, John K. ($350), for your beyond-outrageously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Bryan ($70), for your superbly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

This Nails It: The Doom Loop of Housing Construction Quality 16 Apr 1:59 PM (2 days ago)

Add in the doom loop of an unprecedented credit-asset bubble and housing as a sector is in trouble.

Sorry for the punnish-ment, but this nails it:

How Contracting Work Became a Race to the Bottom The reality of being a contractor includes labor shortages, brutal competition and low, low margins.

This is not a new or unique trend, but it's accelerating into a Doom Loop where the resources needed to reverse the decay are no longer available at the needed scale.

As a former builder, I experienced this same dynamic back in the 1980s, after the 1981-82 recession gutted the auto and construction industries. The 1981-82 recession was the deepest economic decline since the Great Depression in the 1930s, as the Federal Reserve jacked up interest rates to snuff out the inflation expectations that were becoming embedded in the economy.

Sectors that depended on consumer borrowing--autos and housing--tanked. Contractors' sunk capital--the investment of time and effort required to learn the tradecraft, the financial investment in tools and equipment, office leases, etc. and the social capital of relationships forged with subcontractors, suppliers, lenders, etc.--is substantial and not easily replaced.

So everyone in the trades tries to survive the downturn by cutting costs, as the alternative--walking away from the construction industry and trying to establish a new career in a field that pays as well as construction--was difficult enough in good times, but in a recession became nearly insuperable.

The building trades are unique in a number of ways. Skilled labor still commands a higher-than-average wage, which offers a rare leg up for those (mostly men due to the physical demands of the work) with little interest or aptitude for classrooms or white-collar office work.

While manufactured housing and kit homes have been around for decades (Sears sold kit homes in the early 1900s with great success), the trades cannot be fully automated. Housing is one of the few things that's still expected to be durable, and so as dwellings age, repairs are needed, and each situation has both commonalities with similar repairs and aspects unique to the specific problem.

All dryrot is the same, but each instance of rot is unique, and it takes a great expanse of varied experience to figure out the most efficient and effective solution.

Those with deep tradecraft skills are naturally reluctant to abandon their livelihood, but recessions leave many with no choice. Before giving up, contractors will lower their bids to get work just to pay the bills, never mind make a profit.

Offices can be given up, but there isn't much fat to be cut out of bids, as labor, materials and overhead expenses cost what they cost.

There is one big expense that is temptingly open to arbitrage: labor overhead, the non-wages costs paid by employers for tradecraft workers. Due to the physicality and inherent risks of construction, injuries are common and so construction workers compensation insurance rates are high--generally between 25% and 50% of the hourly wage, but can approach 100% for high-risk work categories.

There's a raft of other labor overhead expenses: disability insurance, unemployment insurance, and the employer's share of Social Security, currently 7.65%. In recessions, state unemployment funds are drawn down and so the rate paid by employers increases sharply to replenish the fund.

Some states mandate healthcare insurance coverage for all full-time workers (or all employees working more than 20 hours, etc.), which is another labor overhead.

Add these up and the cost may equal or exceed the wages paid to the worker. To pay a worker $25 an hour, the contractor is paying $50 per hour. So to survive lean times and not go bankrupt from a low bid, contractors either pay workers cash (i.e. under the table) to avoid paying the labor overhead, or they hire quasi-legal subcontractors who do the same thing--pay all their workers as 1099 independent contractors who are responsible for their own insurance, Social Security taxes, etc.

The subcontractors aren't paying their workers $50 an hour, they're paying them $25 an hour, and the 1099 workers don't pay any overhead except the Social Security / Medicare taxes, if that.

This was my experience in the early 1980s as the Great Recession crushed new housing and remodeling. The only contractors who made money were those who avoided paying labor overhead. The rest of us scraped by doing all the work ourselves or we lost money. (The old joke: we lose money on every job but we make it up on volume.)

As the article describes, the same dynamic gutted the sector in the aftermath of the 2008-09 Global Financial Meltdown, with one key difference: many of the older, experienced tradecraft workers have retired or left the construction industry, and the people doing the work now often lack the kind of deep, varied experience needed to do work above the most routine kind.

I've discussed the crippling long-term consequences of this under-competence at some length: workers are trained just enough to competently complete routine tasks, but they lack the training and experience needed to problem-solve / do demanding work outside the narrow boundaries of routine tasks.

The Catastrophic Consequences of Under-Competence (8/17/24)

Automation Institutionalizes Mediocrity (2/14/25)

The soaring costs of materials and construction-related regulatory burdens have now systemically optimized construction-worker under-competence as contractors cannot afford to hire competent workers and still win bids. Homeowners facing sticker-shock on bids for repairs, additions and remodels gravitate to the lowest bid regardless of such niceties as contractors paying all the required labor overhead.

The combination of high costs, optimization of under-competence and the scarcity of truly experienced workers generates a doom loop: shoddy workmanship and low-quality materials cause leaks, but few have the experience to make the needed difficult repairs.

The cultural penchant for McMansion-style homes with complicated roofs generate more opportunities for slipshod workmanship to cause leaks, and the substitution of cheap materials adds to these risks, many of which remain hidden until major damage has been done behind the drywall or siding.

McMansion-style homes built in a hurry by inexperienced crews may pass the purchaser's home inspection, but harbor defects that will manifest later as horrendously costly repairs.

As for who can do the work competently and on time--good luck finding "old timers" who are still in the trades. Those few who can do the work have high costs and are often booked far in advance, and so they can charge a premium. As a result, you hear about roof replacement bids in the $40,000 to $60,000 range--sums that would have been considered astronomical in decades past.

Many homeowners can't swing the costs of repair, so the house rots away.

Personally, I wouldn't do any work in this environment by bid; I'd only work by the hour. This requires an element of trust in the contractor to not pad the daily expenses, but unfortunately it's boiling down to either take a chance on the low bid, knowing the workers are likely getting stiffed because the labor overhead costs that protect them aren't being paid, or the customer pays the contractor the full costs plus a fee for their time and expertise.

There aren't many old hands left in the trades who have the decades of experience necessary to do a wide range of tasks.

Add in the doom loop of an unprecedented credit-asset bubble and housing as a sector is in trouble.

Here's a snapshot of housing affordability, which is in the basement:

The monthly payments are at historic highs, while the cost of non-mortgage expenses such as home insurance and property taxes soar.

If you can find an old hand who's still working, don't try to chisel their price down or hurry them. Be grateful you'll only pay once, cry once rather than pay later and cry a river.

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Roger H. ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Jackson T. ($7/month), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, John K. ($350), for your beyond-outrageously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Bryan ($70), for your superbly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Trade, Tariffs, Currencies, Colonialism, the Gold Watch and Everything 14 Apr 7:14 AM (4 days ago)

The present-day tariff-trade-war conflicts boil down to Neocolonial strategies to gain control of markets for exports and resource extraction on terms that are only favorable to the Neocolonial power.

The title of today's essay pays homage to the inimitable John D. MacDonald's novel The Girl, the Gold Watch & Everything in which the gold watch has the power to stop time.

In the context of today's keening cries of tariff-trade-war agony, let's use this imaginary power over time to return to the ancient world's many long, dangerous and immensely profitable trade routes, for example the (mostly) sea route from Rome to the ports and riches of the southern coast of India, an enduringly profitable trade bonanza ably described in The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: Rome's Dealings with the Ancient Kingdoms of India, Africa and Arabia.

Let's start by dispensing with the conveniently pliable fantasy of "free trade." Though some reckon the author's estimate that 30% of the Imperial income resulted from Rome's duties on foreign trade exceeds the actual percentage, the trade's great volume through the customs offices in Alexandria are described in ancient texts.

On the Indian side of the trade, various restrictions limited Roman access to approved ports and local merchants' dealings with visiting Roman ships and merchants, who established permanent polyglot colonies of Mediterranean traders in Indian ports.

What characterized this trade was not that it was "free" but that it was mutually beneficial and not within the control of either side of the trade. Rome ruled the Mediterranean largely by extending the mutual benefits of commerce to the territories it had conquered. Pay your taxes and customs duties, and all would be well. Try to eliminate the Imperial slice of the pie--now that would bring trouble in the form of legions.

Even if Rome had hankered to control the coast of southern India, it could not project power that distance with the modest craft of the day, and to what benefit when trade delivered goods and income without the horrendous expenses of transporting troops and supporting permanent garrisons? For their part, Indian merchants established trading communities in ports on the Red Sea but relied on Roman policing to protect the land route across the desert to the Nile.

Once technologies enabled imperial ambitions to extend across the globe, then two profitable possibilities emerged in the form of Mercantilist Colonialism. Once an imperial power wrested power from local rulers and established a colony, two profitable forms of commercial control could be imposed:

1) The colonial subjects could be forced to buy manufactured / finished goods produced by the imperialist nation's home economy, guaranteeing a reliable market for its value-added exports, and

2) The colony's natural resources could be secured at low prices for the express use of the Imperialist domestic economy.

In the post-colonial era, mercantilist advantages were gained by severely restricted imports while flooding the domestic economies of trading partners with below-cost goods, driving domestic competitors out of business and establishing a quasi-monopoly that could be exploited once the competition had been eliminated.

These mercantilist strategies were typically hidden within regulatory thickets rather than visible tariffs. For example, in the 1960s and 70s, Japan mastered the art of limiting goods imported from the U.S. via various bureaucratic subterfuges while making full use of the relatively open door to Japanese exports.

(As I have explained in numerous essays, this policy was the direct result of America's Cold War with the Soviet Union, which incentivized the U.S. to support its allies' postwar economic recovery by opening the vast American market to their exports.)

Currency manipulation plays a key role in the mercantilist strategy of restricting imports while flooding others' economies with exports. By devaluing one's currency, the cost of imports rises while the cost of one's exports priced in competing currencies declines.

In effect, currency devaluations act as a hidden tariff on imported goods which soar in price, while slashing the price of exports in economies with strong currencies.

The quasi-monopolies created by mercantilist policies are forms of Neocolonialism--colonialism imposed not by military force but by currency manipulation and state support for exports and bureaucratic thickets that limit finished-goods imports.

The profits from this mercantilist Neocolonialism are then used to buy up mines, ports, agricultural land, etc. in resource-rich nations--another form of Neocolonialism, that is, control of markets and resources by means of mercantilist finance rather than military force.

Another mercantilist strategy is to demand transfers of intellectual property / patents as the price of access to local markets, which turn out to be heavily restricted via bureaucratic thickets.

Financialization is another form of Neocolonialism: flood a smaller target economy with low-cost credit at a scale never before available, indebt the target populace as they snap up motorbikes and other goods previously out of reach, then as they default in the inevitable bubble pop / recessionary hangover, buy up land and other assets on the cheap.

(For example, the Thai Baht lost half its value in the complex Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98, plummeting from 25 to 56 to the US dollar. Thai assets were then "on sale" for those holding US dollars.)

Once the ensuing sovereign debt crisis crashes the local currency, this too is advantageous, as the financiers' currency gains purchasing power, in effect putting all assets priced in the local currency on sale.

The present-day tariff-trade-war conflicts boil down to Neocolonial strategies to gain control of markets for exports and resource extraction on terms that are only favorable to the Neocolonial power.

If everything else fails, Mercantilist Exporters will devalue their currencies to raise the cost of imports and slash the costs of its exports in targeted economies. The danger here of course is a race to the bottom as other mercantilist nations dependent on exports devalue their currencies.

Neocolonialism also plays out in the home economies in perverse ways. When American corporations chose to offshore the nation's industrial base to increase their profits, this in effect gutted Flyover America in the same way a Neocolonial power guts a rival's domestic economy.

I addressed many of these dynamics 13 years ago in The E.U., Neofeudalism and the Neocolonial-Financialization Model (May 24, 2012).

Welcome to Neocolonialism, Exploited Peasants! (October 21, 2016).

Let's call it what it is: a struggle of Mercantilist-Financial Neocolonialism that manifests as Trade, Tariffs, Currencies, Colonialism and Everything. As for the gold watch, we can't stop time but we can imagine the end-game of currency devaluations and the demise of Mercantilist-Financial Neocolonialism.

My book Global Crisis, National Renewal discusses America's opportunity to establish a sustainable economy that will dominate not by force or the subterfuge of mercantilism but by becoming a model of efficient use of resources, capital and labor: the opposite of the Mercantilist Landfill Economy that now dominates the global economy.

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Laura D. ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Guy W. ($7/month), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, John M.G. ($108), for your outrageously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Eugene K. ($20), for your most generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Last Gasp of the Landfill Economy 10 Apr 2:14 PM (8 days ago)

It seems we're supposed to mourn the last gasp of The Landfill Economy. Perhaps we should celebrate its demise.

Globalization's great gift wasn't low prices--it was the collapse of durability, transforming the global economy into a Landfill Economy of shoddy products made of low-cost components guaranteed to fail, poor quality control, planned obsolescence and accelerated product cycles--all hyper-profitable, all to the detriment of consumers and the planet.

Globalization also accelerated another hyper-profitable gambit:

In The Landfill Economy, Consumer choice is pure illusion. I'd like to buy once, cry once, so where is the option with a 10-year all parts and labor warranty? There isn't one, because nothing is durable--by design or default.

As a result, The Landfill Economy is fundamentally extortionist. We know this product will fail, you know this product will fail, and so here's our offer: buy a 3-year extended warranty for a hefty sum, because we've engineered the product to fail in four years.

If the product is digital, then even if it still functions, we'll force you to replace it via a new product cycle: we no longer support the old operating system, and since your device is out of date (heh) it can't load the new OS, and since all the apps now only function with the new OS, your device is useless.

The low price is also illusory, as we now have to buy four, five or ten products instead of one durable product. Appliances that once lasted 40 years now fail in 6 or 7 years if not sooner, so over the course of 40 years we have to buy five, six or seven appliances instead of one.

Note that these durable products weren't super-expensive commercial appliances; they were ordinary consumer appliances produced domestically in vast quantities.

Digitization is a key driver of The Landfill Economy, as cheap electronics all fail, and the product / vehicle / tool becomes a brick. Since inventory is an expense, it's been eliminated, so parts for older products are soon out of stock and unavailable.

In a few years, the firmware is no longer supported, and in a few decades, nobody will even know what coding was embedded in the chipset, but it won't matter anyway, because the chipsets are long gone.

Readers tell me vehicles are now wondrously reliable. Um, yeah, until they need to be repaired. Then the cost is higher than what I've paid for entire used cars.

A friend was showing us his 1957 Chevrolet Bel-Air. Unlike the stainless steal and low-quality chrome of today, the original parts are still untarnished. Since the entire vehicle is analog, parts can be scrounged or fabricated or swapped out with a similar set-up.

Does anyone seriously believe that a chipset-software-dependent vehicle today will still be running 68 years from now? Analog parts can be cast or welded; customized chipsets and firmware coding cannot. The original components will all be history.

Our friend recounted a very typical story about repairing his recent-model pickup truck. Since the engine was no longer responding to the accelerator, he borrowed a diagnostic computer (horribly expensive to maintain due to the extortionist monthly fee to keep the software upgraded) and came up with zip, zero, nada.

After swapping out the fuel pump at great expense and finding the problem persisted, he went online to YouTube University and found one video that explained the relay box from the accelerator to the engine didn't show up in the diagnostic codes, so the problem could not be identified.

The relay box cost $400, and likely consisted of components worth no more than a few dollars each. So after $1,000 in parts and his own labor, the problem was finally fixed. If this qualifies as "super-reliable and maintenance-free," then the diagnosis is obvious: mass delusion.

So now the status quo is desperate to maintain the global assembly lines feeding the hyper-profitable Landfill Economy. This may well be the last gasp of The Landfill Economy, as the supply chains of shoddy products designed to fail will break and consumers may well awaken to the high cost over time of an economy based on planned obsolescence, accelerated product cycles and extortionist illusions of choice.

Last week I bought an expensive portable solar panel manufactured in China from a local distributor. The U.S. brand distributing the product has a good reputation for quality. Of course the warranty is for one year.

The panel failed in less than a week: I smelled the unmistakable odor of an electrical short (insulation melting) and noticed the plastic rectangle that the output cord extended from was dimpled by high heat. The plastic part had no visible way to open it, and no visible way to replace it. So the entire panel is unrepairable.

(The local distributor had one in stock, so I was able to get a replacement. Here's hoping it has a non-defective set of components.)

It's doubtful anyone has the parts in stock, and it's also doubtful that it could be repaired even if one pried open the plastic casing to examine the melted bits. The parts are in one place--the factory that assembled the panel.

So this panel, manufactured at great expense of costly materials, will end up in the landfill after five days of service. And no, it won't be recycled, as there's no system to do so, and it doesn't make financial sense to even try.

Wow, isn't The Landfill Economy fantastic? Look how profitable it is, as consumers must constantly replace or repair at great expense everything that comes off the wonderful global supply chains. And since we worship "growth" and profits, The Landfill Economy is the ideal arrangement--for those making and selling all the stuff.

For the consumers--not so much, but who cares, since they have no choice but to keep buying shoddy products designed to fail.

Add the defective solar panel to the long list of other failed products in our household: the iPhone screen that failed, the washer that failed, the dryer that failed (which I was able to fix by replacing the motherboard, which only cost half the price of a new dryer with my "free" labor), the failed fridge, defective toaster from Walmart, shoes from Costco that fell apart in a few months, and the failed AC system in our 2016 Honda Civic. (Mention this to any mechanic and they quickly nod, "oh yeah, those all fail.")

All of this failure generates "growth" and profits, the two Grails every economist worships. Here's another load of "growth" going straight into the landfill.

It seems we're supposed to mourn the last gasp of The Landfill Economy. Perhaps we should celebrate its demise.

New podcast: The Coming Global Recession will be Longer and Deeper than Most Analysts Anticipate (42 min)

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Melissa B. ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Rarksin Farms ($7/month), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, Neil ($70), for your magnificently generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Remo ($7/month), for your superbly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

A Decade of Headwinds 9 Apr 2:16 PM (9 days ago)

These headwinds will persist for the next decade or two.

The stock market is rallying hard after a brutal sell-off--not an uncommon occurrence. As we savor our winnings in the ship's first-class casino, it's not a bad idea to step out onto the deck and gauge the weather.

There are headwinds. Not zephyrs, not gusts, just steady, strong headwinds.

1. Presidents Trump and Xi view each other an as existential challenge to the future prosperity of the nation they lead. Neither can afford to lose face by caving in, and each has a global strategy with no middle ground.

2. Global trade / capital flows are all over the map. Uncertainty is the word of the moment, but perhaps the more prescient description is unpredictability: if enterprises have no visibility on the future costs of trade, commodities, labor and capital, they have little choice but to avoid big bets until visibility is restored.

3. The American consumer is tapped out. Credit card charge-offs are rising, auto loan defaults are rising, air travel is faltering--there are many sources of evidence that consumers--especially the top 20% households whose spending has propped up the economy--have reached financial and perhaps psychological limits.

4. The Reverse Wealth Effect is kicking in as stocks and other assets roll over into volatility and potential trend changes into declines rather than advances. The top 10% who own the majority of income-producing assets and risk assets are seeing $10 trillion of losses followed by recoveries of $5 trillion. Swings of such magnitude do not support confidence in the stability of current valuations or offer visibility on the odds of future capital gains.

Just as enterprises must respond to poor visibility by reducing risk, households respond to increasing volatility and unpredictability by reducing borrowing and spending. Stable gains in asset valuations fuel the Wealth Effect, encouraging consumers to borrow and spend more because their wealth has increased. The Reverse Wealth Effect triggered by losses, volatility and low visibility encourages reducing risk, borrowing and spending.

5. There will be no "save" by the Federal Reserve or massive new Federal fiscal largesse. Tariffs and reshoring manufacturing are inflationary, so the Fed no longer has the freedom to create a few trillion dollars out of thin air to juice risk assets. The federal government's borrowing-and-spending spree threatens the integrity of the nation's currency and economy, so the the unlimited checkbook has been put in the drawer.

6. The two decades of deflation generated by China has ended. Central banks could play in the Zero-Interest Rate Policy sandbox because inflationary forces were all offset by the sustained deflationary forces of China's export machine and credit expansion. Now every economy, including China's, faces inflationary tides from a number of sources.

7. The sums required to rebuild America's industrial base will pinch speculative borrowing and consumer spending. Now that both the Fed and the federal government are restrained from borrowing and blowing additional trillions, private capital will have to be enticed into long-term investments in Treasury bonds and reshoring. The ways to incentivize long-term investing rather than consumption and speculation are recession and deflating asset bubbles. Both re-set expectations, risk appetites and incentives.

Everyone with direct experience of manufacturing and supply chain networks is telling us that reshoring will be a costly, long-term project, requiring the rebuilding of the entire ecosystem that's been lost to hyper-globalization's offshoring and hyper-financialization's predation.

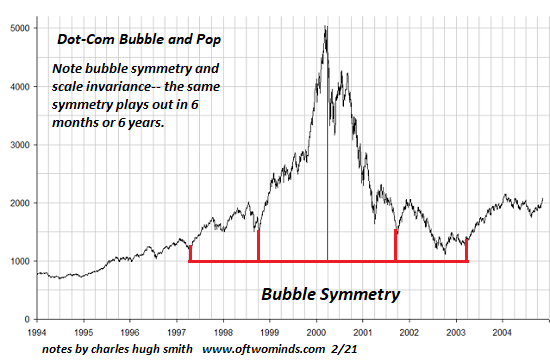

Note that all credit-driven asset bubbles pop. Yes, the market is rigged, but that doesn't mean it always goes up or it's easy to catch the declines. The dot-com bubble lost 80% of its peak valuation despite assurances that was "impossible."

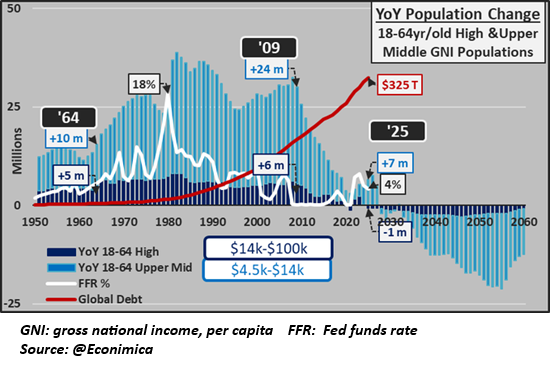

8. Demographics are not supportive of risk-asset expansion. Courtesy of @Econimica, consider this chart of the year-over-year change in high and high-middle-income populations globally. The change is now negative--fewer folks are entering these categories. In response, global debt has soared, in effect offsetting the decline of consumer demographics with borrowed money.

As the global Boomer population retires and needs at-home or institutional care, they will sell their assets to fund these soaring expenses: stocks, bonds, real estate--all will go on the auction block to raise cash.

The older cohort of investors is also more risk averse, as they know they don't have a decade or two to recover from a catastrophic decline in their assets' valuations.

None of these dynamics can be reversed. These headwinds will persist for the next decade or two.

New podcast: The Coming Global Recession will be Longer and Deeper than Most Analysts Anticipate (42 min)

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Steve B. ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Christine M. ($70), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, Benjamin W. ($70), for your magnificently generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Chris G. ($32.40), for your superbly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

The Financial Kessler Effect 7 Apr 9:31 AM (11 days ago)

Like orbiting space debris, every loan that has been collateralized by an illiquid asset is a high-speed projectile with the potential to disable any other part of the system it impacts.

Complex systems can undergo what's known as phase shifts, where the state of the system changes abruptly. The classic example of this is liquid water turning to ice. Since the mechanisms at work--temperature, saline levels, etc.--is known and measurable, then this phase transition is predictable.

Complex systems with emergent properties are unpredictable, and so their phase transitions catch us off guard. The system looks stable, as the risk of sudden instability resolving in a phase shift is not visible.

Emergent properties arise from the interactions of various parts of the system rather than from the characteristics of the parts themselves. Interactions in complex systems that are tightly bound --i.e. highly interconnected--are dynamic and so the consequences of unexpected interactions are unpredictable.

In other words, we think we understand all the possible interactions, but we're forgetting second-order effects: first-order effects: interactions have consequences. Second order effects: consequences have consequences.

This illusion of control leads us to tinker with systems such as the global financial system to suppress any interactions we see as threatening the stability of the entire system. But this tinkering to lower risk has a hidden consequence.

As Nassim Taleb noted in a 2011 article: "Complex systems that have artificially suppressed volatility become extremely fragile, while at the same time exhibiting no visible risks."

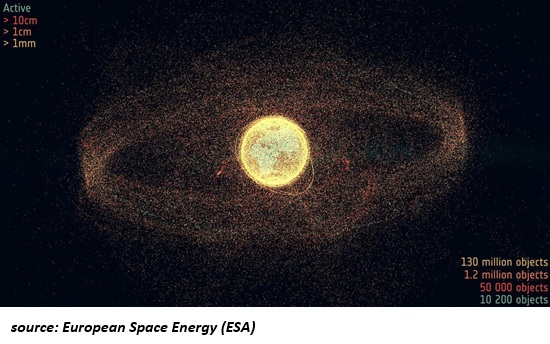

Which brings us to a second example of a phase shift: The Kessler Syndrome: The Kessler syndrome, proposed by NASA scientist Donald Kessler, describes a hypothetical scenario where the accumulation of space debris in Earth's orbit triggers a chain reaction of collisions, creating even more debris, potentially rendering parts of space unusable.

While this is described as "hypothetical," the potential for a Kessler Effect to occur rises sharply with the quantity of space junk / debris speeding around low-Earth orbits in what I call The Orbital Landfill, a space-age analog of The Landfill Economy we've created here on the planet's surface.

And voila, the number of bits of high-speed debris is rising, along with the number of satellites being lifted into orbit:

Catastrophe Looms Above: Space Junk Problem Grew 'Significantly Worse' In 2024 That's brings us to the nightmare scenario that should fill you with dread: The Kessler Effect.

I submit that the Kessler Syndrome is an apt analogy for what may be happening in the global financial system: interactions that few anticipated are setting off second-order consequences that are themselves interacting with other parts of the system in unpredictable ways that will cascade, in effect clearing entire orbits of the global financial system.

So once a margin call impacts a functioning satellite and shatters it into random projectiles, the fallout / debris from that impact then strikes everything that is tightly bound to that part of the system.

These consequences then impact other parts, triggering margin calls and liquidation of assets that then shatter and those destructive projectiles become so numerous that they clear the entire orbit of functional parts of the system.

In a financial Kessler Effect, every critical element is shattered into dangerous debris that cascades through the entire global system.

Being tightly bound, the global financial system is exquisitely sensitive to cascading margin calls and forced liquidations of assets. Like orbiting space debris, every loan that has been collateralized by an illiquid asset (i.e. an asset that can't be sold with the click of a button and the transaction clears second later) is a high-speed projectile with the potential to disable any other part of the system it impacts.

The problem with markets that Taleb described so succinctly is that the risk of apparently liquid markets freezing up and becoming illiquid is not visible until it's too late to sell. Conventional market theory holds that there will always be a buyer to take an asset off a seller's hands. But buyers disappear in crashes, as nobody wants to catch the falling knife.

Assets that were presumed to be liquid become illiquid, and their valuation plummets. This collapse of collateral then triggers margin calls (loans being called in, demands for cash) which then trigger more liquidations into an illiquid market.

And that's how a Financial Kessler Effect clears entire orbits of the global financial system. What looked robust and low-risk is reduced to debris.

New podcast: The Coming Global Recession will be Longer and Deeper than Most Analysts Anticipate (42 min)

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Ryan R. ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Diane M. ($25), for your most generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, Steve W. ($70), for your magnificently generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Daniel T. ($32.40), for your superbly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

After the Tariff Earthquake 4 Apr 8:52 AM (14 days ago)

The fires that have been ignited are not yet visible.

There's a eerie calm after an earthquake. Those trapped in collapsed buildings are aware of the consequences, but the majority experience a silence, as if the world stopped and has yet to restart. The full consequences are as yet unknown, and so we breathe a sigh of relief. Whew. Everything looks OK.

But this initial assessment is off the mark, as much of the damage is not immediately visible. As reports start coming in of broken infrastructure and fires break out, we start realizing the immensity of the damage and the rising risks of conflagration. Uncertainty and rapidly accelerating chaos reign.

President Trump used a medical analogy for what I'm calling The Tariff Earthquake: the patient underwent a procedure and has had a shock, but it's all for the good as the healing is already underway.

We often use medical or therapeutic analogies, but in this case the earthquake analogy is more insightful in making sense of what happens to economic structures that have been systemically disrupted.

The key parallel is the damage is often hidden, and only manifests later. The scene after the initial shock looks normal, but water mains have been broken beneath the surface, foundations have cracked, and though structures look undamaged and safe, they're closer to collapse than we imagine, as the structural damage is hidden.

Another parallel is the potential for damage arising from forces other than the direct destruction from the temblor. The earthquake that destroyed much of San Francisco in 1906 damaged many structures, but the real devastation was the result of fires that started in the aftermath that could not be controlled due to the water mains being broken and streets clogged with debris, inhibiting the movement of the fire brigades, which were inadequate to the task even if movement had been unobstructed.

The earthquake damaged the city, but the fire is what destroyed it.

What was considered rock-solid and safe is revealed as vulnerable in ways that are poorly understood. Structures that met with official approval collapse despite the official declarations. What was deemed sound and safe cracked when the stresses exceeded the average range.

The Tariff Earthquake exhibits many of these same features. Much of the damage has yet to reveal itself; much remains uncertain as the chaos spreads. Like an earthquake, the damage is systemic: both infrastructure and households are disrupted. The potential for second-order effects (fires in the earthquake analogy) to prove more devastating than expected is high.

(First order effects: actions have consequences. Second order effects: consequences have consequences.)

The uncertainty is itself a destructive force. Enterprises must allocate capital and labor based on forecasts of future supply and demand. If the future is inherently unpredictable, forecasting becomes impossible and so conducting business becomes impossible.

Just as the 1906 fires sweeping through San Francisco were only contained by the US Army blowing up entire streets of houses to create a fire break, the containment efforts themselves may well be destructive. We had to destroy the village in order to save it is a tragic possibility.

Here is a building damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake that struck the San Francisco Bay region. The residents may have initially reckoned their home had survived intact, but the foundation and first floor were so severely damaged that the entire structure was at risk of collapse.

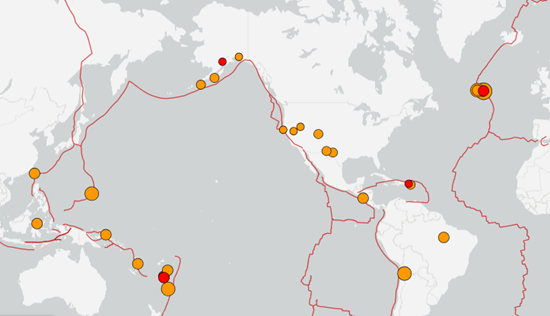

On this USGS map of recent earthquakes around the world, note the clustering of quakes on the "Ring of Fire" that traces out the dynamic zones where the planet's tectonic plates meet. Earthquakes can trigger other events along these dynamic intersections of tectonic forces.

In a similar fashion, The Tariff Earthquake is unleashing economic reactions across the globe, each of which influences all the other dynamic intersections, both directly and via second-order effects generated by the initial movement.

Anyone claiming to have a forecast of all the first-order and second-order effects of the The Tariff Earthquake will be wrong, as it's impossible to foresee the consequences of so many forces interacting or make an informed assessment of all the damage that's been wrought that's not yet visible.

The fires that have been ignited are not yet visible. They're smoldering but not yet alarming, and so the observers who are confident that everything's under control have yet to awaken to the potential for events to spiral out of control.

New podcast: The Coming Global Recession will be Longer and Deeper than Most Analysts Anticipate (42 min)

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Randall R. ($200), for your beyond-outrageously generous founding subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Mark H. ($7/month), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, Michael R. ($70), for your magnificently generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Wanda O. ($70), for your superbly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

The Global Trade Game: Jokers Are Wild 2 Apr 9:45 AM (16 days ago)

There may be no winners of the game of Global Domination (tm), and that is likely the best outcome.

Okay, players: jokers are wild, but with a twist: the entire deck is jokers. Since everyone at the table will have five Aces, nobody wins.

Welcome to the Trade War Poker Table: nobody wins, as everyone has the same hand of jokers.

This is not to say that exploitive, mercantilist "free trade" (no such thing has ever existed) is desirable, much less possible. We're reaping the consequences of what was passed off as "free trade": corporations gleefully gutted National Security to boost profits by offshoring everything that could be offshored.

Every nation can impose tariffs or limit imports by other means. Tit for tat tariffs, concessions, grand deals, side deals--everyone has access to the same deck of cards. Who wins each round of play is an open question, as is who wins the game.

There are several time-tested strategies in the game for Global Domination (tm). One is domination gained by exporting far more than you import, building up treasure in the form of vast trade surpluses.

The problem with this strategy is eventually the nations being stripped by your mercantilist strategy wise up and limit your exports. There is only one way to get around this: military force, i.e. establish a Colonial Empire in which your colonies are forced to buy your surplus production (exports) via a bayonet in their back.

Absent force and a colonial empire, mercantilism is eventually defeated by its own success.

There is another way to play for Global Domination (tm), and it's the exact opposite of mercantilism: run large, sustained trade deficits by importing more than you export, which beneath the surface is a remarkable flow of trade: the importing nation "exports" its currency in size in exchange for goods and services.

Once this currency is "exported" in sufficient quantities, it becomes the dominant currency simply from its ubiquity, its liquidity (i.e. its quantity and ubiquity make it easy to trade everywhere) and its trustworthiness due to its wide ownership across global markets: since the currency is spread across the globe, the issuing nation no longer controls its valuation; that's now set by the market.

This is Global Domination (tm) via financing trade rather than by running trade surpluses by exporting tangible goods. Pick one, as you can't have both: either export goods to run mercantilist trade surpluses, and build up a trove of other nation's currencies, or "export" your own currency via sustained trade deficits so it becomes the global lingua franca of financing trade.

Due to the demands of the Cold War, this was the U.S. strategy in the postwar era. As I have often explained, the U.S. was not merely in an arms race with the Soviet Union; it was also in a war for influence and alliances. The strongest adhesive in alliances is self-interest; by absorbing the surplus production of its allies in Europe and Asia in exchange for dollars, the U.S. cemented alliances that essentially encircled the Soviet Empire.

This strategy was far more effective than open conflict, but it came with a cost. Just as the success of mercantilism generates its own undoing, so too does maintaining a reserve currency via trade deficits / exporting one's currency. Should the issuing nation (in this era, the U.S.) decide to limit imports and reduce its trade deficit, its currency will slowly lose the global scale needed to sustain its market dominance.

This is Triffin's Paradox, which I've addressed many times over the years: any currency--and the system for creating and distributing the currency--has two masters it cannot possibly serve equally: the domestic economy and the global economy. Any nation that wants to control the valuation of its currency cannot possibly achieve global financial dominance, as the only way to gain and maintain global financial dominance is to surrender control of the currency's valuation to the market via exporting currency in such vast quantities that the global market sets the value.

There's a profound irony in this. To manage the domestic economy, the state wants to control everything: the issuance of currency and its valuation via its relative abundance or scarcity, which is reflected in the cost of credit (i.e. interest rates) and asset prices.

But to gain the high ground in the global financial landscape, the currency must serve the global demand for a currency that is ubiquitous, extremely liquid and trustworthy precisely because its value cannot be reset by state diktat. The valuation of a truly global currency is constantly influenced by interest rates, bond issuance, demand and so on--all the features of a transparent marketplace.

The game of Global Domination (tm) will never be decided by a deck of jokers. The real game is 5-card draw: you play the cards you've been dealt by Nature, history, culture and chance. Every nation has a spectrum of strengths and weaknesses, advantages and disadvantages. Some are rich in resources, some are poor in resources. Some have advantageous geography, some less so. Some have cultural coherence, others have diversity; each is a strength and a weakness.

In Nature, the winner is not necessarily the strongest or the one most blessed by chance. The winner tends to be the one with the greatest capacity and incentives for flexibility, experimentation, a level playing field (i.e. social mobility) decentralized capital and all the traits of fast adaptation: if not an appetite then at least a capacity for a continual churn of instability, failure and self-criticism, which are the necessary components of experimentation.

There may be no winners of the game of Global Domination (tm), and that is likely the best outcome. Any form of dominance generates its own undoing.

New podcast: The Coming Global Recession will be Longer and Deeper than Most Analysts Anticipate (42 min)

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, DawgPond ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Lucia U. ($70), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, Peter C. ($70), for your magnificently generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Gavin G. ($70), for your superbly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Why the Global Recession Will be Deeper and Longer Than Pundits Anticipate 31 Mar 9:56 AM (18 days ago)

The global recession will be deeper and longer than those relying on models based on the past two decades of hyper-globalization and hyper-financialization anticipate.

While everyone focuses on conflicts between nations, few look at the problems shared by nations. Richard Bonugli and I discuss both sets of problems in our latest podcast.

The conflict sphere is dominated by the trade wars that are bubbling up here in the first inning of the global rebalancing of national interests and global trade/financial frameworks. Supporting these frameworks benefits participating nations until they don't, at which point they're jettisoned.

The conviction that these frameworks, linch-pinned by the U.S. since the end of World War II in 1945, no longer serve America's core national security interests, is reaching a rough consensus, and as a result some describe the U.S. as a "rogue superpower." In other words, now that the U.S. is no longer the dumping ground for global surpluses of production, it's seen as "going rogue."

There's a certain naivete in the notion that any nation acts selflessly for the good of all. All nation-states act in their own interests, just as global corporations act to optimize shareholder value and profits while proclaiming the wonderfulness of their products and services. Nations support cooperative arrangements when it benefits them, and exit those arrangements when they morph from benefit to burden.

This rebalancing of cooperation and self-interest is taking place in the larger context of non-trade problems shared by all developed nations. Developing nations share many of these same problems as well: soaring debt loads, resource scarcities, corruption, mal-investment, high inflation, stagnating economies, aging populations, shrinking workforces, rising social costs and massive public health issues, many of which have been expanding rapidly behind the focus on trade and conflicting interests.

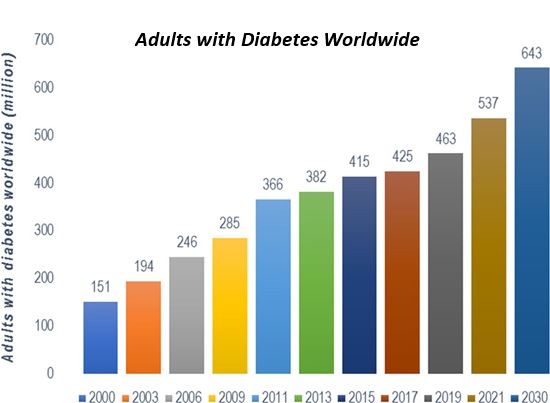

The ubiquity of these issues is striking. In some ways, developed nations share more problems than they seem to realize. Consider the global rise of lifestyle diseases generated by dramatic shifts in diets and fitness. These manifest as metabolic disorders (prediabetes, diabetes) and a broad range of other chronic diseases such as heart disease and cancers.

Metabolic disorders generated by changing lifestyles are now weighing heavily on nations around the world, from the U.S. and Mexico to China, India, the Mideast and beyond.

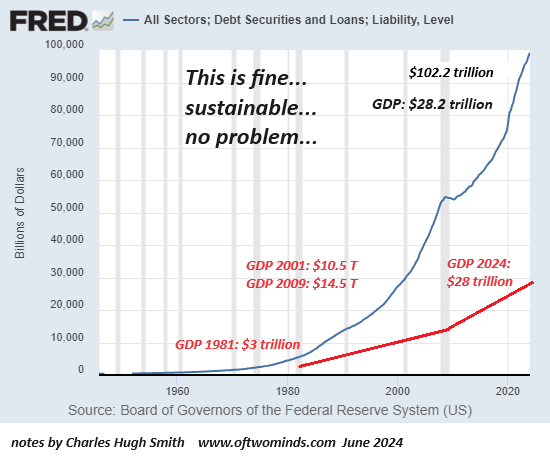

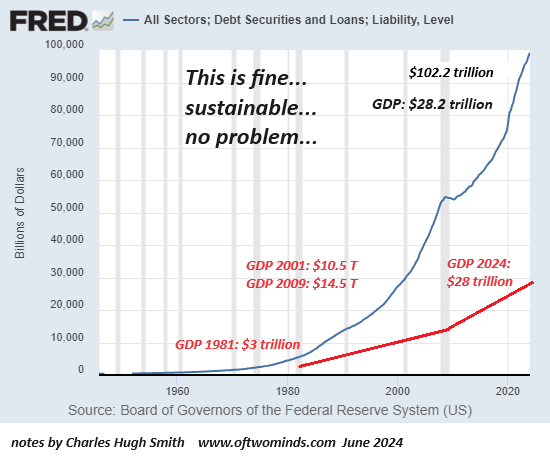

The problems generated by aging populations and declining birthrates are also shared by many nations. The same is true of rising debt levels, both public and private, which threaten to destabilize economies via either ruinously high inflation or fiscal frugality, i.e. austerity. Here is total credit in the U.S., a sobering chart that mirrors the debt loads of many other nations--debt that is outstripping GDP and income as interest rates rise in the new era of global inflationary forces.

The world's nations have awakened to the risks of becoming dependent on other nations for essential commodities, manufactured goods and markets. Tariffs may well be merely the at-bat players in the first innings. If history is any guide, outright bans on imports from selected nations will eventually be viewed as the only available option to rebalance national security priorities.

The degrees of national dependence will become increasingly consequential as mercantilist nations that have relied on exports for growth will find markets for their exports shutting down, crippling domestic growth. Nations that attempt to become self-sufficient will find the demands for capital investment will pressure consumer spending, even as the decline of cheap imports institutionalizes inflation and price increases that outstrip wage increases.

Stagflation will hinder both investment and consumer spending. Austerity will crimp fiscal borrowing and spending, and capital sloshing around the world seeking low-risk returns will face unprecedented challenges as capital controls proliferate and nations change the rules overnight.

I often focus on scale because this is a limiting factor. While there may well be growth opportunities for investing in developing nations, the scale of capital sloshing around global markets will find the investment pipelines the equivalent of a straw: there is no way to deploy $100 billion in small markets and economies, never mind $1 trillion or $10 trillion.

As Immanuel Wallerstein observed, Capitalism may no longer be attractive to capitalists as all these dynamics play out in a vast, inter-connected, unpredictable rebalancing of global interests and increasingly destabilizing attempts to solve complex, intractable problems with cobbled-together expediencies or doing more of what's already failed.

There won't be any "saves" in this rebalancing, and so the global recession will be deeper and longer than those relying on models based on the past two decades of hyper-globalization and hyper-financialization anticipate.

New podcast: The Coming Global Recession will be Longer and Deeper than Most Analysts Anticipate (42 min)

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Larry M. ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Gordon L. ($70), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, Alan D. ($70), for your magnificently generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Kurt N. ($70), for your superbly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Ultra-Processed Life 27 Mar 9:28 AM (22 days ago)

Consuming more of this Ultra-Processed World is not a path to "the good life," it's a path to the destruction and derangement of an Ultra-Processed Life.

The digital realm, finance, and junk food have something in common: they're all ultra-processed, synthetic versions of Nature that have been designed to be compellingly addictive, to the detriment of our health and quality of life.

In focusing on the digital realm, money (i.e. finance, "growth," consuming more as the measure of all that is good) and eating more of what tastes good, we now have an Ultra-Processed Life. All three-- the digital realm, money in all its manifestations and junk food--are all consumed: they all taste good, i.e. generate endorphin hits, and so they draw us into their synthetic Ultra-Processed World.

We're so busy consuming that we don't realize they're consuming us: in focusing on producing and consuming more goods and services as the sole measure of "the good life," it's never enough: if we pile up $1 million, we focus on piling up $2 million. If we pile up $2 million, we focus on accumulating $3 million. And so on, in every manifestation of money and consumption.

The digital realm consumes our lives one minute and one hour at a time, for every minute spent focusing on a screen is a minute taken from the real world, which is the only true measure of the quality of our life.

Ultra-processed food is edible, but it isn't nutritious. It tastes good, but it harms us in complex ways we don't fully understand.

This is the core dynamic of the synthetic "products and services" that dominate modern life: the harm they unleash is hidden beneath a constant flow of endorphin hits, distractions, addictive media and unfilled hunger for all that is lacking in our synthetic Ultra-Processed World: a sense of security, a sense of control, a sense of being grounded, and the absence of a hunger to find synthetic comforts in a world stripped of natural comforts.

In effect, we're hungry ghosts in this Ultra-Processed World, unable to satisfy our authentic needs in a synthetic world of artifice and inauthenticity. The more we consume, the hungrier we become for what is unavailable in an Ultra-Processed Life.

We're told there's no upper limit on "growth" of GDP, wealth, abundance, finance or consumption, but this is a form of insanity, for none of this "growth" addresses what's lacking and what's broken in our lives, the derangements generated by consuming (and being consumed by) highly profitable synthetic versions of the real world.

Insanity is often described as doing the same thing and expecting a different result. So our financial system inflates yet another credit-asset bubble and we expect that this bubble won't pop, laying waste to everyone who believed that doing the same thing would magically generate a different result.

But there is another form of insanity that's easily confused with denial: we are blind to the artificial nature of this Ultra-Processed World and blind to its causal mechanisms: there is only one possible output of this synthetic version of Nature, and that output is a complex tangle of derangements that we seek to resolve by dulling the pain of living a deranged life.

We're not in denial; we literally don't see our Ultra-Processed World for what it is: a manufactured mirror world of commoditized derangements and distortions that have consumed us so completely that we've lost the ability to see what's been lost.

Ultra-processed snacks offer the perfect metaphor. We can't stop consuming more, yet the more we consume the greater the damage to our health. The worse we feel, the more we eat to distract ourselves, to get that comforting endorphin hit. It's a feedback loop that ends in the destruction of our health and life.

Once we've been consumed by money, the digital realm and ultra-processed foods, we've lost the taste for the real world. A fresh raw carrot is sweet, but once we're consuming a diet of sugary cold cereals and other equivalents of candy, we no longer taste the natural sweetness of a carrot; it's been lost in the rush of synthetic extremes of salt, sugar and fat that make ultra-processed foods so addictive. To recover the taste of real food, we first have to completely abandon ultra-processed foods--

Go Cold Turkey.

The idea that we can consume junk food and maintain the taste for real food in some sort of balance is delusional, for the reasons stated above: junk food destroys our taste for real food and its artificially generated addictive qualities will overwhelm our plan to "eat healthy" half the time.

Just as there is no "balance" between ultra-processed food and real food, there is no balance between the synthetic Ultra-Processed World and the real world. We choose one or the other, either by default or by design.

Credit--borrowing money created out of thin air--is the financial equivalent of ultra-processed food. The machinery that spews out the addictive glop is complicated: in the "food" factory, real ingredients are processed into addictive snacks. In finance, reverse repos, swaps, derivatives, mortgages, etc. generate a highly addictive financial product: credit.

Just as with ultra-processed food, the more credit we consume, the more it consumes us. I owe, I owe, so off to work I go.

The derangements of synthetic food, digital realms and finance have yet to fully play out. Consuming more of this Ultra-Processed World is not a path to "the good life," it's a path to the destruction and derangement of an Ultra-Processed Life.

New podcast: Roaring 20s or Great Depression 2.0? (40 min)

My recent books: