Refusal of Medical Treatment in Patients Who Attempted Suicide 4 Jul 2017 2:42 PM (7 years ago)

Case Summary 1,2,3

Kerrie Wooltorton was a 26-year-old woman with a history of mental illness and prior suicide attempts with anti-freeze ingestion who presented to the emergency department of a hospital in the United Kingdom in 2007 after intentionally ingesting a toxic amount of antifreeze. She presented with the following letter:

To whom this may concern, if I come into hospital regarding taking an overdose or any attempt of my life, I would like for NO lifesaving treatment to be given. I would appreciate if you could continue to give medicines to help relieve my discomfort, painkillers, oxygen etc. I would hope these wishes will be carried out without loads of questioning.

Please be assured that I am 100% aware of the consequences of this and the probable outcome of drinking anti-freeze, eg death in 95-99% of cases and if I survive then kidney failure, I understand and accept them and will take 100% responsibility for this decision.

I am aware that you may think that because I call the ambulance I therefore want treatment. THIS IS NOT THE CASE! I do however want to be comfortable as nobody want to die alone and scared and without going into details there are loads of reasons I do not want to die at home which I realise that you will not understand and I apologise for this.

Please understand that I definitely don’t want any form of Ventilation, resuscitation or dialysis, these are my wishes, please respect and carry them out.

When asked about her wishes and care she stated, “It’s in the letter, it says what I want.” She was deemed to have capacity regarding decisions about her care and died in the hospital two days later.

Assessment of Capacity 4,5

An assessment of capacity requires patient understanding of the nature of offered treatment as well as adequate comprehension, retention and processing of treatment information lending to articulate communication regarding the patient’s status relative to the proposed treatment plan.

There is a consideration that the gravity of the potential implications of the patient’s decision require a commensurate increase in the security of the assessment of competence.

Principles of Medical Ethics

The primary principles in medical ethics impacted in the presented case are the respect for autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence. A respect for autonomy affords patients the right to make decisions regarding their medical care based on their personal beliefs and values. Affronts to this principle – by providing treatments without informed consent or after competent refusal – violate the patient’s autonomy.

If, however, the patient lacks capacity, the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence take precedence – as an incompetent patient is unqualified to express their wishes and unauthorized interventions may be performed to help the patient and prevent further harm.

Capacity in Patients with Self-Injurious Behavior 6,7,8,9

Does self-injurious or suicidal behavior itself demonstrate a lack of capacity – independently negating the principle of autonomy and requiring medical interventions to support patient well-being?

One study analyzing decision-making competence comparing patients with attempted suicide (of varying degrees of lethality) to non-suicidal though depressed patients and psychiatrically healthy participants using a scoring tool for the assessment of decision-making competence suggested that suicidal patients may be susceptible to biases that may affect reliable decision-making.

The justification for paternalistic intervention in suicide attempts rests on the notion that a suicide attempt implies a lack of rational decision-making capacity by showing a disrespect for human life, violating a duty for contribution to society, and emotionally harming friends and family. Each of these apparent affronts to rational decision-making has reasonable rebuttals. First, the individual should be afforded the right to assess the value of their own life and an attempt at suicide need not necessarily demonstrate a lack of respect for all life. Second, one’s obligation to society should at least be balanced with society’s obligation to respect the individual’s autonomy – further, compulsory interventions would themselves incur costs to society. Finally, the possibility of harm to friends and family requires the presence of emotionally-attached dependents and is unlikely to be universally true. Presuming all suicide attempts to be rooted in incompetent or biased decisions is likely inaccurate and more nuanced analysis of individual scenarios is warranted to protect individual autonomy.

My Experiences

Unfortunately, I have encountered several patients who have survived self-inflicted injuries – often refusing treatment on presentation. These patients are frequently in critical condition, requiring immediate diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Luxuries like time and a detailed Advance Directive as in Kerrie Wooltorton’s case are rarely available. Interventions proceed emergently, without informed consent and occasionally against the patient’s often vehemently expressed wishes. These cases are extremely troubling to me as I think I rank the respect for autonomy highest among the principles of medical ethics. If the decision for suicide was made autonomously and competently, the lengthy and often traumatizing course for these patients is likely to be only more detrimental to their well-being – such that the principles of respect for autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence are all disrupted.

Do you think that an attempt at suicide necessarily demonstrates an irrational decision? Is it the obligation of the healthcare provider to disregard the patient’s wishes, intervening with life-saving measures assuming their presentation to be the result of a transient miscalculation of the value of their own life?

References

- Dyer C. Coroner rules that treating 26 year old woman who wanted to die would have been unlawful. BMJ. 2009;339. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4070.

- McLean SAM. Live and let die. BMJ. 2009;339:b4112. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4112.

- Callaghan S, Ryan CJ. Refusing Medical Treatment After Attempted Suicide: Rethinking Capacity and Coercive Treatment in Light of the Kerrie Wooltorton Case. Journal of law and medicine 18, 811-819 (2011).

- Ryan CJ, Callaghan S. Legal and ethical aspects of refusing medical treatment after a suicide attempt: the Wooltorton case in the Australian context. Med J Aust. 2010;193(4):239-242.

- Buchanan A. Mental capacity, legal competence and consent to treatment. J R Soc Med. 2004;97(9):415-420. doi:10.1258/jrsm.97.9.415.

- Jacobson JL, Jacobson AM. Involuntary treatment: Hospitalization and medications. In: Psychiatric Secrets. Harley and Belfus Inc; 2001:536.

- Great Britain. England. High Court of Justice, Family Division. Re C (Adult: Refusal of Treatment). The weekly law reports [1994] Feb 25, 290-296 (1993).

- Szanto K, Bruine de Bruin W, Parker AM, Hallquist MN, Vanyukov PM, Dombrovski AY. Decision-making competence and attempted suicide. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(12):e1590-e1597. doi:10.4088/JCP.15m09778.

- Matthews MA. Suicidal competence and the patient’s right to refuse lifesaving treatment. Calif Law Rev. 1987;75(2):707-758. doi:10.15779/Z384J0G.

The Ethics of Practicing Procedures on the Nearly Dead 31 Oct 2015 10:31 PM (9 years ago)

The report from the field was not promising by any stretch, extensive trauma, and perhaps most importantly unknown “downtime” (referencing the period where the patient received no basic care like CPR). The patient remained pulseless en route, we were all aware of the markedly poor prognosis.

On arrival the patient was swarmed by providers. Trauma surgeons at the foot of the bed cut down at the femoral artery to deploy a device that might mitigate bleeding – still in experimental stages. The patient’s ability to safely breath was certainly compromised, a tube in the trachea will solve that. Where the blood went was the question, tubes inserted into each of his lung cavities could reveal the answer. Replacing some of what was lost was important too, a straw-sized catheter into a major vessel can help there. The surgeons’ device hadn’t had any appreciable impact so a large cut was made across the left side of the chest – might as well examine the heart and hub of potentially bleeding things in the area. The heart was empty, a surefire sign of as yet unidentified bleeding; contractions were rare and spastic. The time of death was declared and the frenzy of activity ceased.

Students and residents crowd around the open chest cavity as the chief resident explains the procedure and exposed anatomy – a student lingers to close the wound. The bedside ultrasound that revealed fluid in the abdomen was repeated and the unique findings were explained to eager learners. People file out slowly, sharing feedback about the resuscitation, it’ll go even smoother next time.

It’s a common scenario. By most measures this patient was both dead and unsalvageable. The futile attempt at resuscitation was recognized by most at the outset, but proceeded because it provided a bounty of critical experiences for trainees at all levels – experiences which in the future could prove life-saving. Ethical concerns surrounding this tacitly recognized activity are plentiful and our unease as providers suggests that we recognize this though are unsure of how to reconcile our feelings. The major difficulties are as follows:

- Patients have a right to have critical procedures performed by experienced providers.

- Effective training requires live practice and can at best be only supplemented by simulation (cadavers/models).

- Obtaining informed consent is challenging. Patients and their families are not adequately educated regarding the nature of medical training and the operation of teaching hospitals. Further, these discussions are often not feasible during a resuscitation, or may appear insensitive after a failed resuscitation.

- Providers may be deceptive by extending failed resuscitations in attempts to secure procedures for trainees.

The importance of these experiences for trainees is without question. Patients deserve to have experienced providers performing critical procedures, though that in turn requires a sufficient number of those very procedures to gain competency. Teaching hospitals mitigate this discrepancy by closely supervising trainees until procedural competency is achieved.

To secure the necessary certification, training programs must provide sufficient exposure to allow trainees to become proficient at the performance of these critical procedures. Most are common enough that trainees gain competency relatively early in the training period. Others are more rare, and unfortunately still more critical. These prized procedures are indicated in only the most critically ill patients – they are staggeringly invasive but potentially life-saving. It is conceivable that experience gained through resuscitations extended despite a low probability of favorable outcome could be beneficial to future patients.

The solution to this predicament is challenging. What is evident is that patients are not sufficiently educated regarding the nature of medical education and that this leads to dishonesty by providers (who are merely trying to secure the training of their residents for the betterment of future patient care) and a critical breach in the implicit trust of the patient-physician relationship. Some possible responses would be to increase awareness of medical education and training practices through public service announcements – followed by an opt-out policy similar to organ donation in many countries. I’m mostly curious to hear what others think of this practice and how you would feel if you or a family member was in a similar situation.

References:

- Jetley AV, Marco CA. Practicing Medical Procedures on the Newly or Nearly Dead. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012:299–310. doi:10.1002/9781118292150.ch27.

The Ethics of Teaching Hospitals 2 Oct 2013 6:54 AM (11 years ago)

I can’t imagine what the patient was thinking. Seeing my trembling hands approaching the lacerations on his face with a sharp needle. I tried to reassure him that I knew what I was doing, but the pair of residents who stood behind me discredited that notion. The procedure took twice as long as a more experienced practitioner, but the end result was – in my perhaps biased opinion – comparable.

Patients at teaching hospitals, perhaps unknowingly, take a large role in the education and development of every stage of trainee in every area of practice. They will likely be interviewed and examined multiple times; their plans of care may change as their case makes its way up the chain of command; and they may undergo supervised procedures performed by less experienced trainees. However, I believe that patients receive superior treatment at teaching institutions as a direct result of the supervised care of trainees who are more curious, active and generally have fewer responsibilities and are able to spend more time with their patients.

Let’s explore the ethics of patient care at teaching institutions, examining how it may affect each of the major principles of medical ethics.

- Autonomy: Individuals have the right to make decisions about their health and what happens to their bodies.

I think there is some infringement on autonomy in teaching hospitals, as patients should expect to be fully informed in order to make reasonable decisions. While patients receive information about the hospital and consent for treatment during registration, it is unlikely that this information is either read or explained appropriately.

I have been guilty of this as well. For example, I intentionally withheld from a patient the fact that I had never performed a particular procedure outside of relatively low-fidelity simulations and had just watched a video explaining how to do it.

It does not respect the patient’s autonomy to hide these facts, as the patient has a right to know and potentially refuse treatment. - Beneficence: The practitioner must act to improve the patient’s health.

The application of this principle is unaffected in teaching institutions. - Non-maleficence: First, do no harm.

It is possible that the participation of less-experienced trainees leads to more errors and the possibility of causing unintended harm. However, the requirement for hands-on experience for trainees is unavoidable. Patient safety should be ensured with continuous supervision and graded responsibility. - Justice: All patients should be treated equitably. All resources should be distributed equitably.

Different teaching institutions vary in their levels of insistence on trainee participation (should a patient refuse that students not participate in his or her care). A violation of this principle would occur if certain populations were more likely to be required to work with trainees. Another possible conflict is if teaching institutions are predominantly located in low-income areas where patients have fewer options.

In summary, I believe that trainee participation in teaching institutions is critical to the development of competent physicians and is therefore an essential component of medical care. The participation of trainees supports the overarching goal of helping people, and the risk of harm can be mitigated by adequate supervision. Finally the principles of autonomy and justice can be upheld if all patients are adequately informed of the ways that trainees may participate in their care and none are allowed to refuse such participation without reasonable concerns.

Have you ever been treated or hospitalized at a teaching institution? What was your experience like?

Conscious Conversation: Behavioral Science 3 Sep 2013 2:08 PM (11 years ago)

This interview is part of a series exploring what different people think about consciousness. The plan is to pose the same basic question to people of different backgrounds (philosophers, religious figures, scientists, politicians, down to my sister), and learn how this affects their view of the world and themselves.

- Dr. Cohan: Science

- Dr. Rapaport: Computation

- Daniel Black: Philosophy

- Dr. Zaidel: Behavioral Science

Dr. Eran Zaidel is a professor of Behavioral Neuroscience and faculty member at the Brain Research Institute at UCLA. His work focuses on hemispheric specialization and interhemispheric interaction during attention, perception, action, emotions and language.

Progress Report 15 Jul 2012 4:10 PM (12 years ago)

Two years down, I’m still going. The next two years are my clinical rotations, the actual hands-on training. It’s a scary prospect, responsibilities and such; but it’s equally exciting, after all, this is what I came here for. I’ll let you know how it goes since I actually have no idea what it’ll be like.

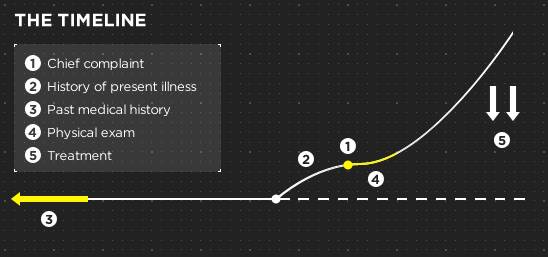

I want to share something that one of my tutors described, the big picture. The timeline below depicts the course of an individual presenting with a typical complaint (ex. cold, shortness of breath, etc). Treating a person is an investigation centered around understanding their health timeline. I’ll describe the points in the timeline in detail below, each point also corresponds to a part of the note that your doctor creates for each encounter.

- The person comes in with a problem, a “chief complaint”. This is already a serious problem for the patient, having become significant enough to outweigh all their other obligations.

- Prior to their presentation today, the patient had a progressive worsening of symptoms. This could have been a fairly rapid progression (ex. the minutes after a car accident), or their condition could have taken a more insidious course (ex. progressively worsening shortness of breath). A critical part of the investigation is understanding what happened in this intervening time, the “history of present illness”. How long has this problem been happening, what can the person tell me about the quality, severity and duration of the problem?

- Of course, there’s a lot more to the story than the time during which symptoms became evident. This part corresponds to several important aspects of the patient’s history that can contribute to a better understanding of the current problem: “past medical history”, “past surgical history”, family history, “social history” (this includes things like work/school history, safety, alcohol and substance use, sexual history), medications, etc.

- The final portion of the information-gathering phase is the physical exam. These are the diagnostic tests and maneuvers that add some objective facts (signs) to the subjective descriptions (symptoms) provided by the patient.

- The final part of the timeline is where we use all the information we’ve gathered to create an “assessment and plan” and hopefully alter the course of the patient’s current diversion.

That’s a pretty basic summary of what’s going on in every visit. Hopefully it’ll help you understand a bit more about the process the next time you see your doctor.

Why Medical School Should Be Free 2 Jul 2012 9:32 PM (12 years ago)

There’s a lot of really great doctors out there, but unfortunately, there’s also some bad ones. That’s a problem we don’t need to have, and I think it’s caused by some problems with the rules about becoming a doctor.

1. The money

Becoming a doctor is expensive. I’m about halfway through and I’m nearly $100,000 in debt. Many “problem” doctors have improper expectations about their value and compensation. Part of this is due to the high cost of medical education, but another cause is this sense that they’re owed more because of the relative difficulty and sacrificed profitability during the long training period.

However, the real value of being a doctor is in the profession itself. Simply put, those who don’t find that sufficient shouldn’t be doctors. It’s not about discouraging people, but if the primary focus is financial, there are probably easier ways of making money.

How do you select for this? Make medical education free and then fix doctors’ pay at a more reasonable rate. People don’t become soldiers for the money, they do it because they believe in their mission. If you take the money out of the equation for becoming a doctor (both the mountain of debt and the tantalizing prospect of success), you get a volunteer army.

2. The education

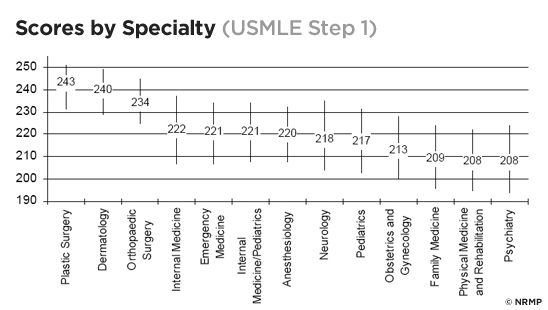

Another problem, both contributing and a result of #1 is the focus of medical education on intelligence, and specifically the measurement and valuation of that quality through standardized tests. Too many potentially great doctors are excluded based on test scores, and just as many potentially bad doctors are funneled in for the same reasons. This pattern continues once in medical school, where a test (unceremoniously called “Step 1”) now helps determine your range of specialties.

Being smart isn’t the most important part of being a good physician, being empathetic, genuinely caring about and able to connect to people is. What’s the point of knowing the molecular underpinnings of a condition if a patient’s never going to trust you enough to tell you what’s really going on?

My experience at UCLA has convinced me that there’s been alot of improvement in this area. We take a course called “Doctoring” that exposes us to different people and situations (through standardized patients) in an environment where we can get guidance from our peers and teachers as we learn our patient’s history, deliver (sometimes bad) news, and provide counseling. It’s an incredible learning experience and I’m sure it’s made me a more caring and compassionate person.

It upsets me when I hear a story about an asshole doctor because they clearly should’ve done something else, and there’s probably someone out there who would’ve made a much better doctor but was turned down because they couldn’t afford it or forgot some utterly useless fact that they could Google on their phone in 10 seconds.

On a side note, have you ever had any bad experiences with a physician? Let me know and I’ll try not to do that.

The Cerebellum: a model for learning in the brain 24 Nov 2011 6:02 PM (13 years ago)

I know, it’s been a while. Busy is no excuse though, as it is becoming clear that writing for erraticwisdom was an important part of exercising certain parts of my brain that I have neglected lately. I have a few Conscious Conversation interviews in queue as well that I’ll be posting soon. So let’s begin.

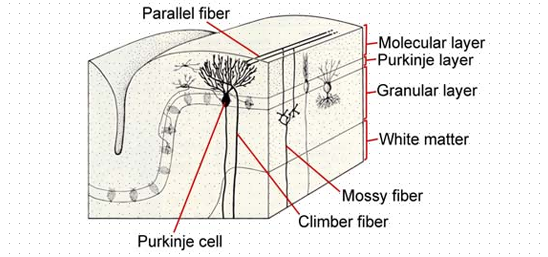

The cerebellum is a beautiful organ, nestled just under its bigger brother. It’s a critical part of controlling movement and serves as an excellent, if simplified, example of learning and memory – with the structure itself helping us understand how it works. The cerebellum provides rapid corrective feedback along the route from upper motor neurons (UMN) in the cortex to lower motor neurons directly innervating muscle. Firing an UMN triggers muscle contraction, but directed movement involves the sustained and coordinated firing of groups of agonist and antagonist muscles that is regulated by structures like the basal ganglia, relay nuclei and our little friend. The cerebellum helps to smooth and fine-tune movement based on its inputs: somatosensory, proprioceptive, visual, auditory and vestibular (hence its defects present with balance problems and with fine motor difficulty).

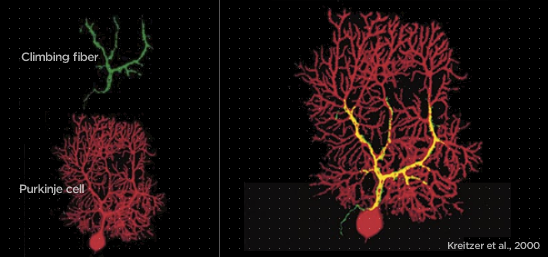

The cellular anatomy of the cerebellum explains a lot about how motor learning works. There are three major types of cells interacting in the cerebellum: Purkinje cells, climbing fibers (from the inferior olive), and granule cells and their parallel fibers. Purkinje cells provide the major output from the cerebellum, firing tonically to suppress movement. They have a large but flat dendritic tree and are stacked along each other in the outer layer of the cortex. They receive nearly 80,000 inputs each from parallel fibers shooting past their dendrites and a single strong input near the body of the Purkinje cell from a climbing fiber. The parallel fibers transmit contextual sensory information from the rest of the brain, while the climbing fibers ascend from the inferior olive and deliver a powerful, complex spike when an error is noticed during a novel task.

Let’s use an example to put this system into motion. Imagine we are trying to learn to respond to a new stimulus. Just like Pavlov’s dogs, we want to associate the response to an unconditioned stimulus, with a conditioned stimulus. When we deliver a puff of air to the subject’s eye, they blink. What we would like to do is associate a tone just before the puff with the blink. We now have a stimulus (the tone) that is sent to the Purkinje cells by parallel fibers, and an error (failure to blink) that is delivered by climbing fibers. This simultaneous activation sets the stage for memory and learning.

When the subject fails to blink in time, the climbing fiber slaps the Purkinje cell for its error, and the Purkinje cell responds by punishing those parallel fiber synapses that were active when the complex spike was received. Activity from the complex spike travels up the dendritic tree to meet with coincidentally active parallel fiber synapses and promotes the removal of neurotransmitter receptors at only these synapses, an enduring process known as long-term depression. Now, the next time the tone is heard, the Purkinje fiber responsible for tonically inhibiting eye blinks is no longer stimulated by the tone-activated parallel fiber and its tonic inhibition relaxes, promoting the desirable blink.

It’s an incredibly elegant system, suitable for such an elegant little brain.

Conscious Conversation: Philosophy 8 Oct 2010 9:45 PM (14 years ago)

This interview is part of a series exploring what different people think about consciousness. The plan is to pose the same basic question to people of different backgrounds (philosophers, religious figures, scientists, politicians, down to my sister), and learn how this affects their view of the world and themselves.

- Dr. Cohan: Science

- Dr. Rapaport: Computation

- Daniel Black: Philosophy

- Dr. Zaidel: Behavioral Science

Daniel Black, author of Erectlocution, was kind enough to chat with me one day and we had a great discussion – have a listen.

The Stuff in Between 1 Aug 2010 9:35 AM (14 years ago)

I’m actually almost normal when not agonizing over robot production details, and quite a bit has happened since I last wrote an update.

First, I’ve finally graduated. I had a bit of a mid-undergraduate crisis and dropped my biology major in favor of a more practical degree in philosophy. With my sister’s help, however, I was able to remember that I did actually want to be a doctor and ended up with degrees in biomedical sciences and philosophy. Sprinkling in a few philosophy classes really helped make my courses more manageable, and it kept my brain from getting fried by tons of rote memorization.

Wanting to be a doctor meant that I needed more than just good grades. Solid GPA’s and MCAT scores guarantee only a fraction of what’s expected of a good physician. So, in addition to getting to know the best spots to study at UB (Lockwood Library, 5th floor), I also had to spend alot of time volunteering, shadowing and getting involved in stuff I liked.

I stayed pretty busy until my fifth year when – having finished my MCAT’s and the most difficult required courses – I finally had some time to relax. I moved every year in college and wasn’t really happy until that last year when my friends and I rented out an entire house on UB’s South Campus. I even managed to squeeze my courses into three days and had Tuesday’s and Thursday’s completely free. The extra time was amazing, I started going to the gym, rock climbing, hiking, gaming, and sleeping in (I even went skydiving).

It was also interview season for medical school and I got to travel to Boston, Miami, Columbus, Los Angeles, Atlanta, and a couple of memorable visits to New York City. After a few panicky months on various waitlists, the acceptances started coming in and I decided I’ll be going to UCLA School of Medicine. I’ve got a long road ahead, but I’ll make it.

Right now, I’m sitting in my grandfather’s house in Baaqline, Lebanon (and I mean his house, he built it – alone – almost 40 years ago). The view is stunning, mountain after mountain to the ocean, some sliced by winding roads and dotted with red-roofed houses, and some that are still completely untouched. I just came back from a walk to the market to pick up some necessities (mosquito repellant and beer) and I’m sitting down to catch a few rounds of yerbe maté with my family. It’s really an amazing place – just yesterday I walked 25 miles up to Nabi Ayoub (a temple to Gob on the peak of a mountain) with my brother-in-law, and then drove down to Beirut to relax on the beach.

Update: Sadly my vacation has come to an end. My sister’s wedding was incredible and I’m back at my new home in Los Angeles, moving and getting ready for school. There’s going to be alot of changes in my life, but I’ve never been more excited (I felt like Harry Potter when I got a list of required diagnostic tools). I’ll always have time to think and write, so thanks for reading and please stay tuned.

The Ethics of AI: Part Three 4 Jun 2010 10:42 AM (14 years ago)

Is it ethical (or possible) to constrain intelligent life?

This part of the argument involves what we think it means to be human, and whether creating and adjusting those criteria in an AI affects what they are capable of.

A critical part of being human is having freedom, the freedom to choose one of many possible actions (some we would deem moral and others immoral). It is these choices we make that – combined with environmental factors – produce an individual. The existence of an individual is of critical importance because it is this variety of conditions and decisions that create all of us, the paradigm-shifting geniuses, mass murderers, and utterly mundane.

One problem that arises immediately when discussing moral AI is whether that freedom, and individuality, remains. Perhaps latent in the term “robot” itself is the notion that constraining a personally intelligent machine such that it is incapable of acting immorally would restrict its freedom. If a machine operated in such a way, it could not comprehend the gravity of making an immoral decision, and it would be difficult to differentiate that machine from other instances that (necessarily) operate in the same way.

However, this is not how I would expect to develop moral artificial intelligence. Rather than creating preprogrammed “moral drones” that are unconsciously restricted from acting immorally, I would create an AI that was aware of the full range of possible decisions, but always (or at least often) acted morally. The distinction here is that our machine would want to act morally. By removing whatever evolutionary propensities for immoral behavior, we could expect our machines to “think clearly” and not only recognize the proper choice, but to seek it willingly (as the consequences, however delayed, would be determined to be desirable). The moral machines needn’t be perfect either (that may well be impossible), but even an incremental improvement would be worthwhile.

I believe this type of moral AI would preserve individuality, because it produces moral behavior not by forcing a particular decision, but by ensuring that moral behavior is always desired. It is not difficult to imagine a nearby possible universe whose inhabitants (through whatever tweaks of nature/nurture) evolved in such a way as to emphasize equality and unity. Their slightly altered nervous systems would imperfectly prefer moral behavior, with relevant changes to their emergent social structure (one perhaps untainted by discriminatory or violent tendencies). Easier still, imagine the person you wish you could be. For example, my good doppelgänger is not as easily influenced by social pressures, he does not spend his money frivolously when it would be better donated, and while this makes him a different individual, he is still an individual.

Freedom is a necessary part of being human, as it allows for individual decisions towards good or evil, but what about evil itself, is it too a necessary human component? Can we know what it means to be good (and to make the necessary individuating choices) if there is no contrasting evil?

If we abolish even the conscious propensity for evil, we don’t necessarily lose the ability to differentiate good. For example, I don’t have to kill someone to learn that it’s wrong. If evil has to exist in some form, then even a memory would suffice as a deterrent. Being human and homo sapiens are not the same thing, evil is only a necessary component of the latter.

It is obvious that free will alone does not constitute individuality, something valuable happens over the course of a conscious being’s life that transforms a cloned instance into an individual. Preserving this process in our AI would be essential to ensuring the same unique development that leads to both genius and the mundane (having hopefully eliminated the profane). The most reliable method for conserving these features is by doing it the homo sapiens way. Instances should be unique and plastic: that is, every AI should be created randomly according to a general blueprint and should be highly flexible. This allows for individual talents (and weaknesses) along with an ability to learn and develop over time.

How would we accomplish something like algorithmically improving the moral behavior of a machine? This is obviously speculative, but it is possible that amplifying the activity of mirror neurons could lead to more moral behavior. Mirror neurons, as their name suggests, reflect perceived behavior as neural activity in the perceiver – they are thought to be responsible for learning language, and perhaps, empathy (Bråten, 2007). For example, when you wince at the sight of someone in pain, it is believed that your mirror neurons are firing a similar uncomfortable pattern, possibly creating a need to help assuage their pain (and ultimately your own). A mirror response strong enough would essentially implant the Golden Rule such that any individual’s suffering would be distributed among the “species” and would produce a widespread effort to reduce it.

In this case, it seems that it is not only possible, but ethically advisable to create moral AI. We sacrifice nothing of what it means to be an individual, and can ensure the moral treatment of individuals in society.

Conclusion

This is where we stand: creating a race of artificially intelligent machines is not ethically permissible since using them as a means to an end (which violates Kant’s categorical imperative) does not afford them the respect they deserve as conscious beings. While it is at least theoretically possible to create AI that behaves more morally than us, the cost of the actual implementation of the project (the species-cide of humanity) is too high to justify. It seems there’s no easy way out.

- Bråten, Stein. (2007). On being moved: from mirror neurons to empathy. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.