Introducing Cards & New Documentation Site 13 May 2:57 AM (7 months ago)

After launching our Reader app just a few weeks ago, I’m happy to announce the arrival of another tool to make learning (and remembering!) German words and phrases a whole lot easier.

Introducing Cards

Cards is our brand-new flashcard app—free to use, globally accessible, and runs straight in your web browser.

Want to dive right in? Use the button below to load some sample decks from my recent book, Easy German Dialogues:

Cards features a clean, minimalist design, works seamlessly on all screen sizes, packs a ton of customization options, and runs a powerful spaced repetition algorithm under the hood.

Wait… another flashcard app?

Yup. I hear you.

There are about a bazillion flashcard apps out there. So why build another one? What makes Cards different from Quizlet, ANKI, or the rest of the bunch?

Glad you asked.

Long before apps and algorithms, people were scribbling words on little Karteikarten¹, flipping them over in train stations, cafés, or just pacing around their living rooms. It was low-tech, sure—but brutally effective.

Today, spaced repetition takes that same idea and supercharges it with science. Instead of reviewing everything all the time, it spaces things out—so you don’t space out (pun fully intended). It shows you harder cards more often and easier ones less frequently, right before you’re about to forget them. And it works. It’s one of the few study methods that’s actually been proven to help you remember stuff long-term.

But here’s the thing…

Most learners fall into two camps:

- The flashcard fanatics (lovingly crafting their decks), and

- The skeptics (who think the whole thing is overhyped nonsense).

With Cards, I wanted to bridge that gap: to make flashcards accessible, especially for people who are new to the concept.

What’s wrong with the other guys?

Over the years, I’ve shipped my ebooks with flashcards in both Quizlet and ANKI format. They both have their strengths. But they also come with some baggage.

Quizlet is online, sure, but you need an account. There are limits on the free plan, and the site is basically a billboard parade of ads.

Anki is free, customizable, and beloved by the hardcore learners—but let’s be honest, it can be intimidating. If you’re already on the fence about flashcards, the idea of installing software, wrangling imports, and navigating its 2002-era UI probably won’t win you over.

That’s where Cards comes in.

No downloads. No installs. No account needed. Once your decks are loaded, you can even go offline—it still works. No data harvesting. No fluff. No friction.

Just a lean, mean study machine, right in your browser. In the spirit of the old UNIX adage: “Do one thing and do it well.”

How does it work?

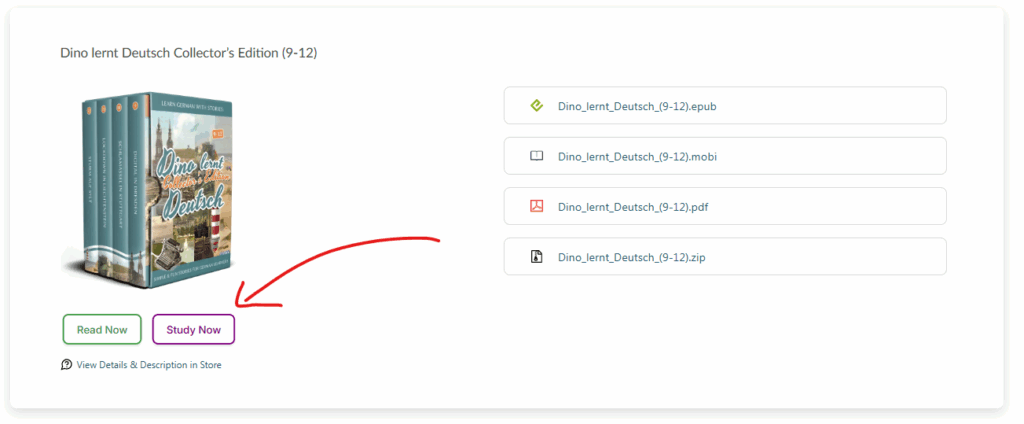

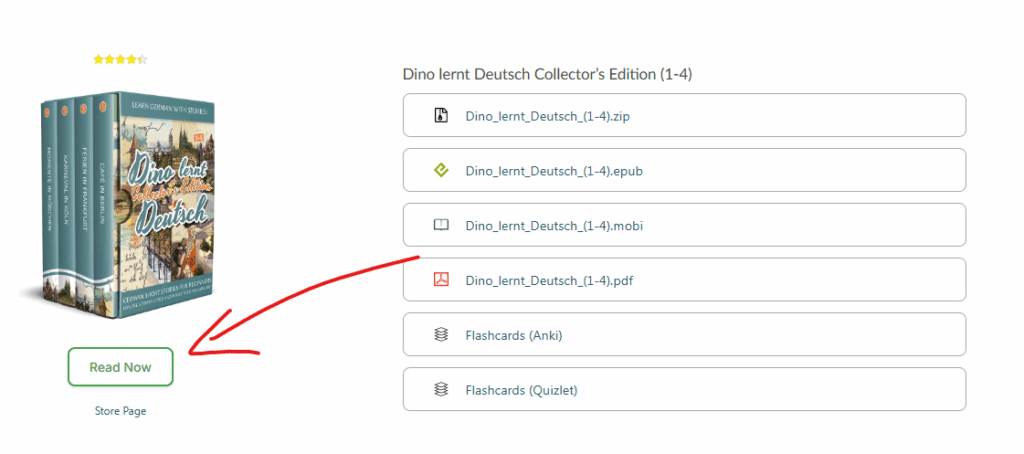

Cards is tightly integrated with our bookstore, so from your account you can now instantly load decks for each of your books via the “Study Now” button.

Even if you got your copy from Amazon, Apple Books, or somewhere else, you don’t need to log in. Just use the updated bonus links at the end of the book to load your decks—or import your own.²

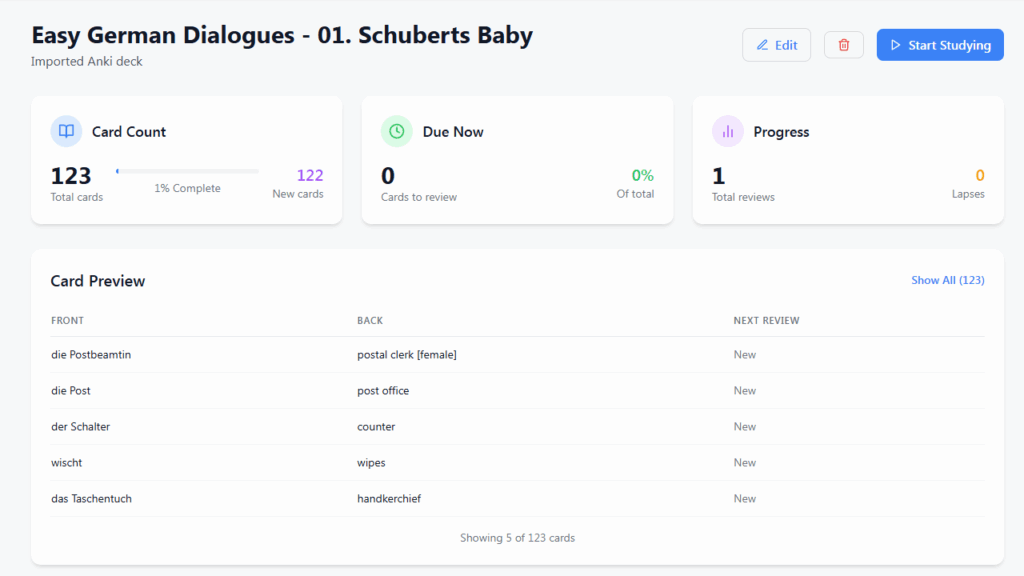

Once loaded, you can browse the cards via the “View Details” screen, check your progress, and tweak cards to your heart’s content.

This is the “View Details” screen. Here you can see your progress for that deck and edit your cards.

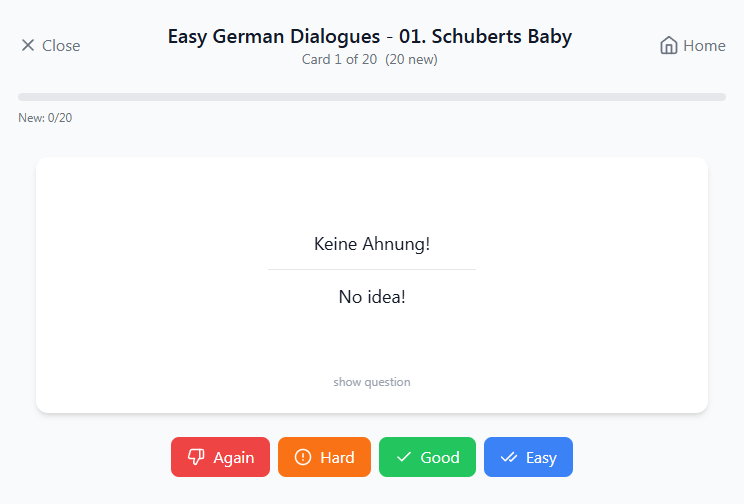

Ready to study? Hit “Study Now” or “Start Studying” and start rating cards based on how tricky they feel. The system will take it from there.

Our spaced repetition algorithm is loosely inspired by the big players, but also adds a few of its own twists. I go into detail about it here if you want to nerd out, but the gist is simple:

Hard cards show up more often. Easy ones fade into the background until they’re needed again. Like little memory goblins. Persistent, annoying, and—eventually—conquered.

New Docs Site

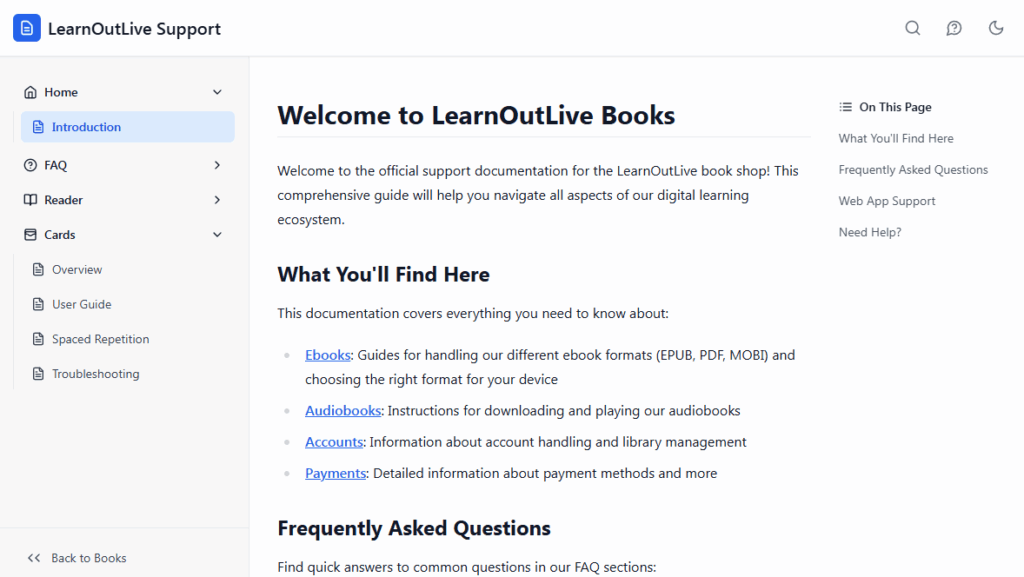

While building Cards, I realized I needed to write up a proper manual. But instead of writing a blog post like a normal human, I built an entirely new documentation site from scratch. Think of it like a mini-Wikipedia for everything LearnOutLive Books.

It covers everything you need to know: ebook formats, detailed guides for Reader and Cards, account related questions, recommended apps and much more.

The new docs site follows the same minimalist vibe: fast loading, tiny memory footprint, dark/light mode (because eye strain is real), and full-text instant search.

Check it out at support.learnoutlive.com

–

¹ German for “index cards”

² Cards currently supports simple front/back flashcards only—tailored for the layout style I use in my books. More info here.

The post Introducing Cards & New Documentation Site appeared first on LearnOutLive.

Introducing Reader 28 Apr 2:46 PM (8 months ago)

I’m excited to introduce a brand-new way to read our German learning books—directly from your library, no downloads or third-party apps required. Just log in to your account, pick a book, click “Read Now” and start reading instantly in your browser.

Prefer your usual ebook app? That still works too. This is simply an additional, more convenient option—especially useful when you’re on a different device or just want to skip the whole EPUB juggling act.

I built Reader from scratch, using the latest technologies in web development, to bring you a reading experience optimized for distraction-free reading (and learning!) with enhanced typography and layout options.

Yes, TalkingBooks work too.

Reader is fully compatible with my TalkingBooks. If you enjoy reading while listening (a fantastic method for language acquisition), you’ll now benefit from improved customization options, smoother performance on mobile, and better highlighting controls.

By the way, the old CloudReader is still available as well, so you can compare both experiences and see which one you prefer.

And yes, Reader is completely free. It’s just another way of giving you the best possible German learning experience.

If you spot anything odd…

I’ve tested Reader on a wide range of devices and formats, but if you encounter any bugs or quirks, feel free to let me know—I always appreciate the feedback.

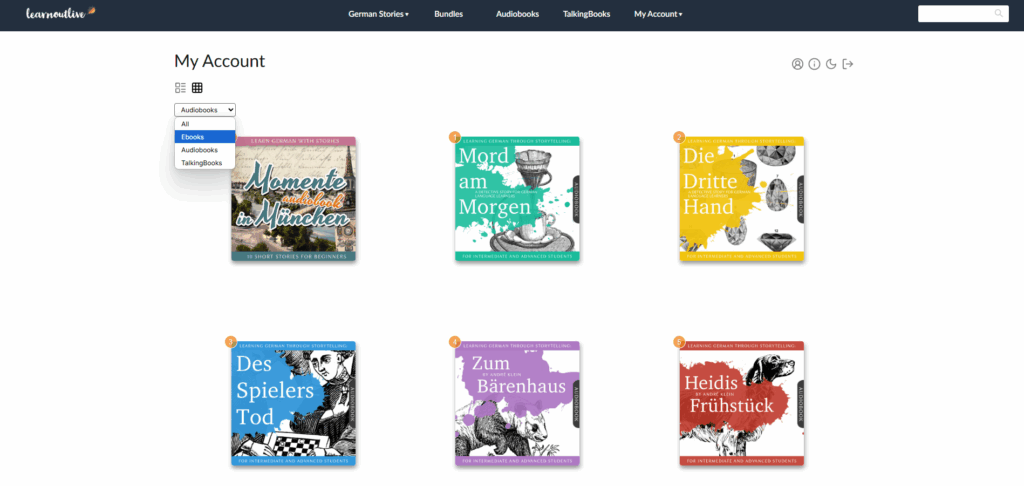

Library Updates

On a similar note, the library has also gotten a face-lift and some new features:

- Dark Mode for late-night study sessions

- A refreshed, modern interface

- Micro message center for in-library updates

- Improved filters and smarter sorting—especially useful if you have a large collection

I have a bunch of other exciting features planned as well, so make sure to log in periodically to see what’s next.

–

The post Introducing Reader appeared first on LearnOutLive.

German Adverbs: The Ultimate Guide For Beginners 22 Mar 10:53 AM (9 months ago)

So, you’ve decided to tackle German adverbs—good choice. These little words are everywhere, slipping into sentences to explain when, where, how, and to what extent things happen. Want to say you really love chocolate? Or that you’ll finally hit the gym tomorrow? Adverbs make it happen.

In this guide, we’ll break down the basics, throw in a handy cheat sheet, and even test your skills with some interactive exercises. Let’s make German adverbs your new best friends.

Ready? Los geht’s! (Let’s go!)

What Are Adverbs & Why Should You Care?

Before we jump in, let’s clear up what adverbs actually are:

Adverbs are words that modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs by telling us how, when, where, or why something happens.

The cool thing about German adverbs? Unlike those pesky adjectives with all their endings, adverbs don’t change their form! That’s right – no matter what gender, case, or number (singular/plural) you’re dealing with, adverbs stay exactly the same. Phew!

Compare these:

Adjective (changes):

Der schnelle Hund gewinnt das Rennen.

(The fast dog wins the race.)

Die schnellen Sportler bekommen Medaillen.

(The fast athletes athletes receive medals.)

Adverb (doesn’t change):

Der Hund läuft schnell.

(The dog runs quickly.)

Die Sportler laufen schnell.

(The athletes run quickly.)

So, unlike in English where adverbs are always marked with the ending “-ly”, in German adverbs have no endings at all, regardless of context.

Types of German Adverbs: The Magnificent Seven

1⃣ Adverbs of Manner (Wie?) – How something happens

These tell us how an action is performed:

- schnell (quickly) → Er läuft schnell.

- langsam (slowly) → Die Schildkröte bewegt sich langsam.

- gern/gerne (gladly/with pleasure) → Ich esse gern Pizza.

- gut (well) → Sie singt gut.

In German we call these Modaladverbien.

Pro Tip: Gern is probably the most useful manner adverb in German! It’s how you express liking to do something: Ich trinke gern Kaffee = I like drinking coffee.

2⃣ Adverbs of Time (Wann?) – When something happens

These tell us when something happens:

- heute (today) → Wir bleiben heute zu Hause.

- jetzt (now) → Ich muss jetzt gehen.

- morgen (tomorrow) → Morgen fahre ich nach Berlin.

- später (later) → Wir können später darüber sprechen.

In German we call these Temporaladverbien.

3⃣ Adverbs of Place (Wo?) – Where something happens

These tell us where things are happening:

- hier (here) → Komm hierher!

- dort/da (there) → Mein Freund wohnt dort.

- oben (up/upstairs) → Die Katze sitzt oben auf dem Dach.

- draußen (outside) → Die Kinder spielen draußen.

In German we call these Lokaladverbien.

4⃣ Adverbs of Frequency (Wie oft?) – How often something happens

These tell us how frequently something occurs:

- immer (always) → Er kommt immer zu spät.

- oft (often) → Wir gehen oft ins Kino.

- manchmal (sometimes) → Manchmal lese ich bis spät in die Nacht.

- nie/niemals (never) → Ich trinke nie Kaffee.

- selten (rarely) → Sie geht selten ins Fitnessstudio.

These are a subset of Temporaladverbien.

5⃣ Adverbs of Degree (Wie sehr?) – To what extent

These express intensity or degree:

- sehr (very) → Sie findet das Buch sehr interessant.

- zu (too) → Es regnet zu viel im November.

- ziemlich (quite/fairly) → Er spielt ziemlich gut Gitarre.

- besonders (especially) → Du sprichst besonders gut Deutsch.

- kaum (hardly/barely) → Ich kann ihn kaum hören.

These also belong to the group of Modaladverbien.

6⃣ Adverbs of Reason (Warum?) – Why something happens

These explain why something happens:

- deshalb (therefore) → Es regnet. Ich bleibe deshalb zu Hause.

- darum (that’s why) → Ich bin krank. Darum komme ich nicht.

- deswegen (because of that) → Es ist spät. Deswegen müssen wir gehen.

In German we call these Kausaladverbien.

7⃣ Modal Particles – The “Flavor” Words

These tiny words add emotion and nuance to German speech:

- doch (contrary to what was thought) → Komm doch mit! (Do come along!)

- mal (softening a command) → Schau mal! (Take a look!)

- eben/halt (simply/just) → Das ist eben/halt so. (That’s just how it is.)

- ja (as you know) → Er ist ja Arzt. (He’s a doctor, as you know.)

Bonus Knowledge: These modal particles are super common in spoken German and will make you sound much more native!

Bonus Knowledge: These modal particles are super common in spoken German and will make you sound much more native!

Note: While these technically belong to the class of (modal) adverbs, their position in a sentence is often much more flexible. See my article on modal particles for a more in-depth take on these. For the rest of this article we will focus on the four main categories of: Temporal, Kausal, Modal and Lokal.

Adverbs vs. Adjectives: The Eternal Confusion

We’ve already established that unlike adjectives adverbs don’t take endings in German, and that there are a bunch of different categories. Adjectives generally describe nouns, whereas adverbs modify verbs. (hence the “ad-verb”). So how about positioning?

| Adjectives | Adverbs | |

|---|---|---|

| Function | Describe nouns | Modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs |

| Position | Before nouns or after “sein” | Usually after verbs |

| Endings | Change based on gender, case, number | No endings, never change |

Now, let’s look into their positioning in more detail.

Where Do I Put These Adverbs? The TeKaMoLo Rule to the Rescue!

In German, word order matters a lot. If you just have one adverb, you’re generally safe to put it after the verb. For multiple adverbs, remember this golden rule:

TeKaMoLo: Temporal → Kausal → Modal → Lokal

This means:

- Time (when?)

- Cause (why?)

- Manner (how?)

- Place (where?)

Let’s see it in action:

Ich fahre morgen wegen des schönen Wetters gerne nach München.

(I’m happily going to Munich tomorrow because of the nice weather.)

- Temporal: morgen (tomorrow)

- Kausal: wegen des schönen Wetters (because of the nice weather)

- Modal: gerne (happily/with pleasure)

- Lokal: nach München (to Munich)

Remember: The main verb in German always goes in position 2 in a normal sentence, and adverbs typically come after it.

Remember: The main verb in German always goes in position 2 in a normal sentence, and adverbs typically come after it.

If you have complex verb forms with multiple parts, the adverb usually goes after the first part, i.e. the auxiliary:

Ich bin in Berlin oft ins Kino gegangen.

(I’ve often gone to the cinema.)

Ich werde morgen schnell eine Bestellung machen.

(I’ll quickly make an order tomorrow.)

Note: Since German word order is very flexible, we can always move adverbs into first position for emphasis. The rest of the adverbs will still be sorted according to TeKaMoLo, however.

Let’s take our example from above with the full chain of adverbs and show how you can move any of them into first position while still maintaining the sorting rule for the rest:

Morgen fahre ich wegen des schönen Wetters gerne nach München.

(I’m happily going to Munich tomorrow because of the nice weather.)

Gerne fahre ich morgen wegen des schönen Wettersnach München.

(I’m happily going to Munich tomorrow because of the nice weather.)

Wegen des schönen Wetters fahre ich morgennach München.

(I’m happily going to Munich tomorrow because of the nice weather.)

The Gern-Lieber-Am liebsten Trio: Expressing Preferences Like a German

One of the most useful adverb sets in German is the gern-lieber-am liebsten trio for expressing preferences:

- gern/gerne = gladly, with pleasure (basic form) Ich trinke gern Tee. (I like drinking tea.)

- lieber = rather, preferably (comparative) Ich trinke lieber Kaffee als Tee. (I prefer coffee to tea.)

- am liebsten = most preferably (superlative) Am liebsten trinke ich heiße Schokolade. (I most prefer drinking hot chocolate.)

Quick Tip: Use these three to talk about your preferences in German – it’s much more natural than saying “Ich mag…” for everything!

Let’s Practice!

Choose the Correct Adverb

German Word Order

Arrange the words to create a correct German sentence following the TeKaMoLo rule.

Your sentence:

Fill in the Blanks

Your Results

In Conclusion: Keep Calm and Adverb On!

Congratulations! You’ve just mastered one of the most important parts of German grammar. Remember:

- Adverbs tell us how, when, where, and why

- They never change their form (hooray!)

- Position matters: follow the TeKaMoLo rule

- Feel free to move adverbs into first position for emphasis

The best way to get comfortable with adverbs? Listen for them in German songs and TV series, spot them them in books or on advertising posters. You’ll start to develop a sense for where they naturally belong.

So go ahead and start using these adverbs oft (often), gern (gladly), and überall (everywhere) in your German conversations!

Viel Erfolg! (Good luck!)

Your German Adverb Cheat Sheet

Here’s a handy reference table of the most common adverbs you’ll need:

Time – Temporal

| German | English | Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| heute | today | Ich arbeite heute. (I’m working today.) |

| morgen | tomorrow | Wir reisen morgen ab. (We depart tomorrow.) |

| jetzt | now | Die Vorstellung beginnt jetzt. (The show starts now.) |

| gestern | yesterday | Wir trafen uns gestern. (We met yesterday.) |

| bald | soon | Er kehrt bald zurück. (He’ll return soon.) |

| früher | earlier, in the past | Die Menschen lebten früher anders. (People lived differently in the past.) |

| später | later | Wir essen später. (We’ll eat later.) |

| sofort | immediately | Komm sofort her! (Come here immediately!) |

| damals | back then | Die Kinder spielten damals draußen. (Children played outside back then.) |

| gerade | just now, right now | Ich koche gerade. (I’m cooking right now.) |

Frequency – Temporal

| German | English | Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| immer | always | Sie lächelt immer. (She always smiles.) |

| oft | often | Wir gehen oft spazieren. (We often go for walks.) |

| nie | never | Er raucht nie. (He never smokes.) |

| manchmal | sometimes | Manchmal jogge ich morgens. (Sometimes I jog in the mornings.) |

| selten | rarely | Sie isst selten Fleisch. (She rarely eats meat.) |

| normalerweise | usually | Normalerweise stehe ich früh auf. (Usually I get up early.) |

| meistens | mostly | Die Sonne scheint meistens im Sommer. (The sun mostly shines in summer.) |

| häufig | frequently | Es regnet häufig im Herbst. (It rains frequently in autumn.) |

| gelegentlich | occasionally | Wir treffen uns gelegentlich zum Kaffee. (We meet occasionally for coffee.) |

Reason & Result – Kausal

| German | English | Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| deshalb | therefore | Es regnet, deshalb bleibe ich drinnen. (It’s raining, therefore I’m staying inside.) |

| darum | that’s why | Der Bus kam spät, darum rannte ich. (The bus came late, that’s why I ran.) |

| deswegen | because of that | Er kam zu spät, deswegen verpasste er den Anfang. (He came late, because of that he missed the beginning.) |

| also | so, thus | Sie studiert Medizin, also lernt sie viel. (She studies medicine, so she studies a lot.) |

| trotzdem | nevertheless | Es regnete, trotzdem gingen wir spazieren. (It rained, nevertheless we went for a walk.) |

| folglich | consequently | Er übte nicht, folglich spielte er schlecht. (He didn’t practice, consequently he played badly.) |

Manner – Modal

| German | English | Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| schnell | quickly | Er läuft schnell. (He runs quickly.) |

| gut | well | Sie singt gut. (She sings well.) |

| gern(e) | gladly, with pleasure | Ich esse gerne Pizza. (I like eating pizza.) |

| langsam | slowly | Sie spricht langsam. (She speaks slowly.) |

| leise | quietly | Die Kinder spielen leise. (The children play quietly.) |

| laut | loudly | Der Hund bellt laut. (The dog barks loudly.) |

| einfach | simply | Du löst die Aufgabe einfach. (You solve the task simply.) |

| natürlich | naturally | Er bewegt sich natürlich. (He moves naturally.) |

| besonders | especially | Sie tanzt besonders elegant. (She dances especially elegantly.) |

| sorgfältig | carefully | Er arbeitet sorgfältig. (He works carefully.) |

| fleißig | diligently | Die Studentin lernt fleißig. (The student studies diligently.) |

| fröhlich | cheerfully | Die Kinder singen fröhlich. (The children sing cheerfully.) |

| traurig | sadly | Sie blickte traurig aus dem Fenster. (She looked sadly out the window.) |

| heftig | violently, intensely | Der Wind weht heftig. (The wind blows intensely.) |

| deutlich | clearly | Er spricht deutlich. (He speaks clearly.) |

| grob | roughly | Er schnitt das Brot grob. (He cut the bread roughly.) |

| vorsichtig | cautiously | Sie öffnete die Tür vorsichtig. (She opened the door cautiously.) |

| freundlich | kindly | Die Verkäuferin lächelt freundlich. (The salesperson smiles kindly.) |

| genau | exactly, precisely | Er misst die Zutaten genau ab. (He measures the ingredients precisely.) |

| eilig | hurriedly | Sie verlässt eilig das Haus. (She leaves the house hurriedly.) |

| mühsam | laboriously | Der alte Mann geht mühsam die Treppe hinauf. (The old man climbs the stairs laboriously.) |

| geschickt | skillfully | Sie löst das Problem geschickt. (She solves the problem skillfully.) |

| energisch | energetically | Er klopft energisch an die Tür. (He knocks energetically on the door.) |

| zärtlich | tenderly | Sie streichelt das Baby zärtlich. (She strokes the baby tenderly.) |

| großzügig | generously | Er spendet großzügig. (He donates generously.) |

| ordentlich | neatly | Sie räumt ihr Zimmer ordentlich auf. (She tidies her room neatly.) |

| schlecht | badly | Er spielt schlecht Klavier. (He plays piano badly.) |

| ungeduldig | impatiently | Die Kinder warten ungeduldig auf den Bus. (The children wait impatiently for the bus.) |

| zufällig | accidentally, by chance | Wir trafen uns zufällig im Supermarkt. (We met by chance at the supermarket.) |

Degree – Modal

| German | English | Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| sehr | very | Sie tanzt sehr elegant. (She dances very elegantly.) |

| zu | too | Du redest zu schnell. (You talk too fast.) |

| ziemlich | quite | Er spielt ziemlich gut Klavier. (He plays piano quite well.) |

| besonders | particularly | Sie singt besonders schön. (She sings particularly beautifully.) |

| fast | almost | Wir hatten fast gewonnen. (We had almost won.) |

| kaum | hardly, barely | Er atmete kaum noch. (He was hardly breathing anymore.) |

| völlig | completely | Der Läufer erschöpfte sich völlig. (The runner exhausted himself completely.) |

| etwa | approximately | Der Zug verspätet sich etwa zehn Minuten. (The train delays approximately ten minutes.) |

| total | totally | Der Film begeisterte mich total. (The movie excited me totally.) |

Place – Lokal

| German | English | Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| hier | here | Wir treffen uns hier. (We meet here.) |

| dort/da | there | Die Kinder spielen dort. (The children play there.) |

| überall | everywhere | Die Leute tanzen überall. (People dance everywhere.) |

| oben | up, upstairs | Die Kinder spielen oben. (The children are playing upstairs.) |

| unten | down, downstairs | Wir essen unten. (We eat downstairs.) |

| drinnen | inside | Wir spielen drinnen Karten. (We play cards inside.) |

| draußen | outside | Die Kinder toben draußen. (The children romp outside.) |

| irgendwo | somewhere | Die Katze versteckt sich irgendwo. (The cat hides somewhere.) |

| nirgendwo | nowhere | Der Ball rollt nirgendwo hin. (The ball rolls nowhere.) |

| links | left | Der Fluss fließt links vom Haus. (The river flows to the left of the house.) |

| rechts | right | Der Weg führt rechts in den Wald. (The path leads right into the forest.) |

–

The post German Adverbs: The Ultimate Guide For Beginners appeared first on LearnOutLive.

NEW: A Fantasy Chat Story For German Learners 28 Jan 12:08 AM (11 months ago)

Since the launch of German Chat Stories last year I’ve been toying around with various ideas and genres that might fit this format.

One idea that has been kicking around in the back of my mind for a while was to do something in the fantasy genre. It came with some interesting implications. If knights and sorcerers used instant messaging apps, what would they talk about? And what “technology” would they use to facilitate these chats?

Well, you can find out for yourselves in my latest story “Die Kugel”. Like the other stories, it’s completely free:

In terms of vocabulary difficulty this one is probably slightly more challenging than the others, but it’s also rather short, which should balance out nicely.

Notes And Considerations

I’ve built a new feature that I call “dynamic quizzes”. In previous stories, there were predefined “checkpoints” where you could do quizzes about words and phrases you interacted with. For this new story, quizzes can now appear at any time during the story, or even be turned off completely if you just want to read/listen to the chat messages. (Quizzes can always be re-enabled in settings.)

Some other tweaks include various performance tweaks and making the default chat speed just a tiny bit quicker, so there is less downtime between messages. Keep in mind that you can customize that in your settings as well.

Also, there was a bug where changing the speed while messages were running would sometimes prevent the next message from showing up. This should be fixed now by applying the new speed settings with a bit of a delay.

Last but not least, while not directly related, this story and the new code was written as part of an experiment to change my desktop environment for a few weeks, ditching Windows and relying on open source operating system and tools only. If you’re interested in these types of things you can read about it on my personal blog.

–

The post NEW: A Fantasy Chat Story For German Learners appeared first on LearnOutLive.

Best Browser Extensions to Translate German Words and Phrases Instantly 25 May 2024 5:01 AM (last year)

Most browsers these days come with built-in machine translation features, so that when you browse a site in a language different than your own you can easily translate everything with one click.

This is great if you just need to look something up quickly, but for language learners, I feel this feature is often less than helpful, because you skip the text-comprehension process entirely, don’t get to use previously learned vocabulary or acquire new words and phrases.

So how can we use digital German-English dictionaries productively when reading web-sites? How to get only translations for specific words and phrases while leaving some room to put our linguistic grey-matter to use?

On mobile operating systems like Android or iOS you can usually long-press a certain word and get translations for just the selected text. For desktop users to get the same functionality, you can use free browser extensions.

Top Chrome Extensions

Many of the following extensions offer full-page translations as well as single word and phrase translation. I will focus only on the latter for now, since this is most helpful for German learners. Also, I’m going to test these extensions without a) creating accounts or b) paying for premium subscriptions so you can see what you get exactly after installing.

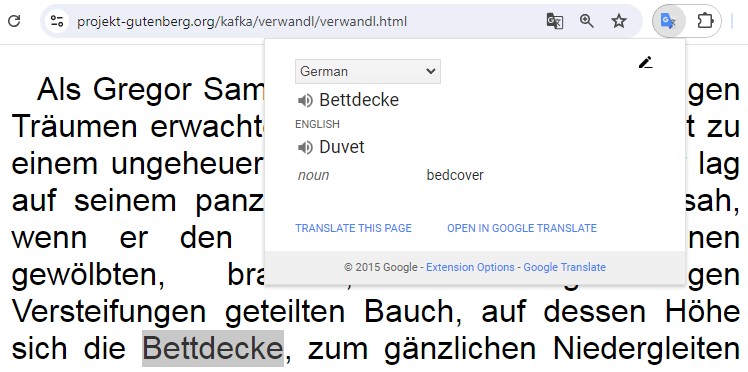

As an example text we’re going to use the first passage from Franz Kafka’s Die Verwandlung from the Gutenberg Project.

Note: the following extensions are all Chrome extensions, but you can use them on any Chromium-based browsers (Edge, Vivaldi, Opera, Brave, etc.). If you don’t use a Chromium-based browser the same (or similar) extensions are also available for Firefox and other browsers.

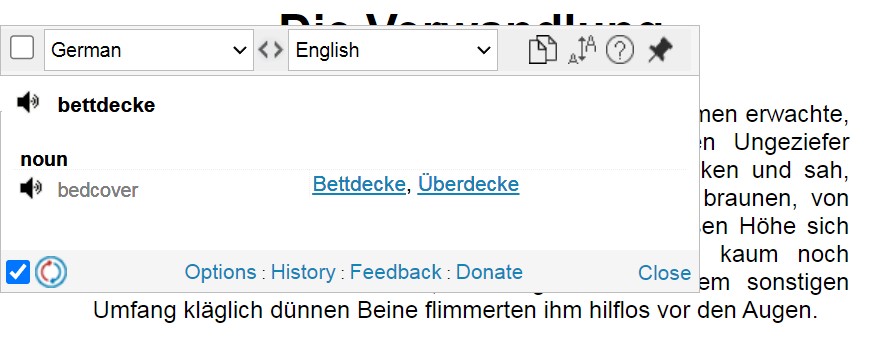

Google Translate

Let’s start with one of the most well-known translation services, Google Translate, in its browser extension form. It’s a very simplistic integration but works pretty well.

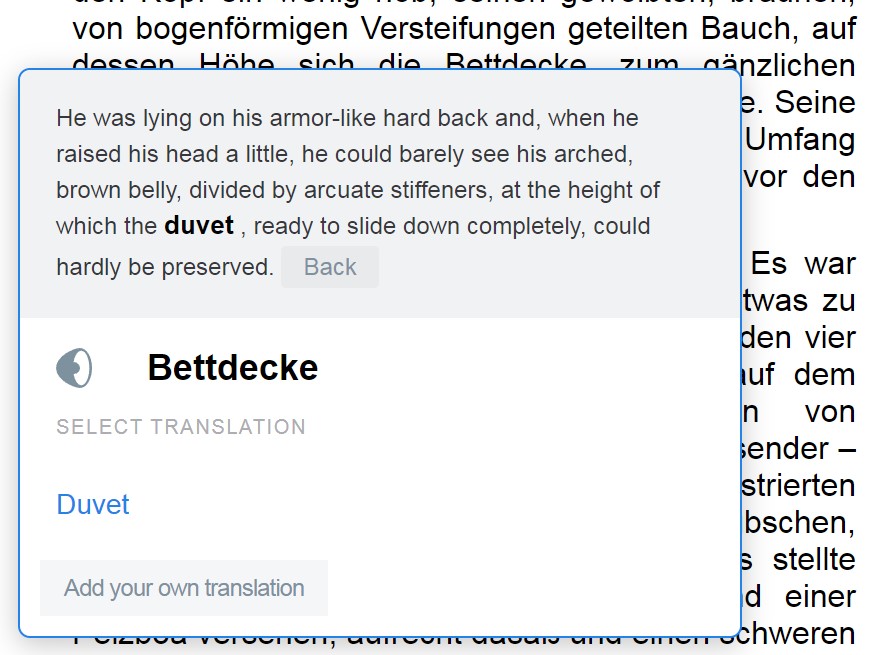

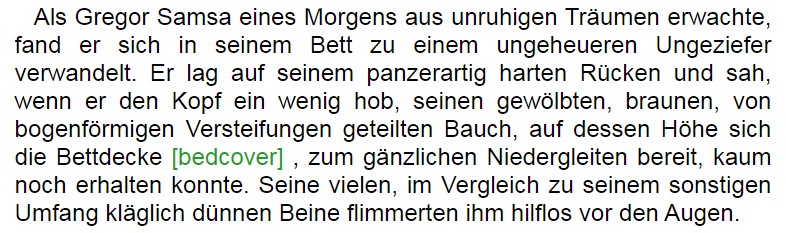

After installing it you get a little translate icon in your browser (make sure to pin it). Select the word you want to translate, then click the Google Translate Button and you will see a popup like this:

Pros: fast, free, reliable, shows multiple translations and type of word (noun, adjective, etc.)

Cons: need multiple clicks to get translation, no immediate popup.

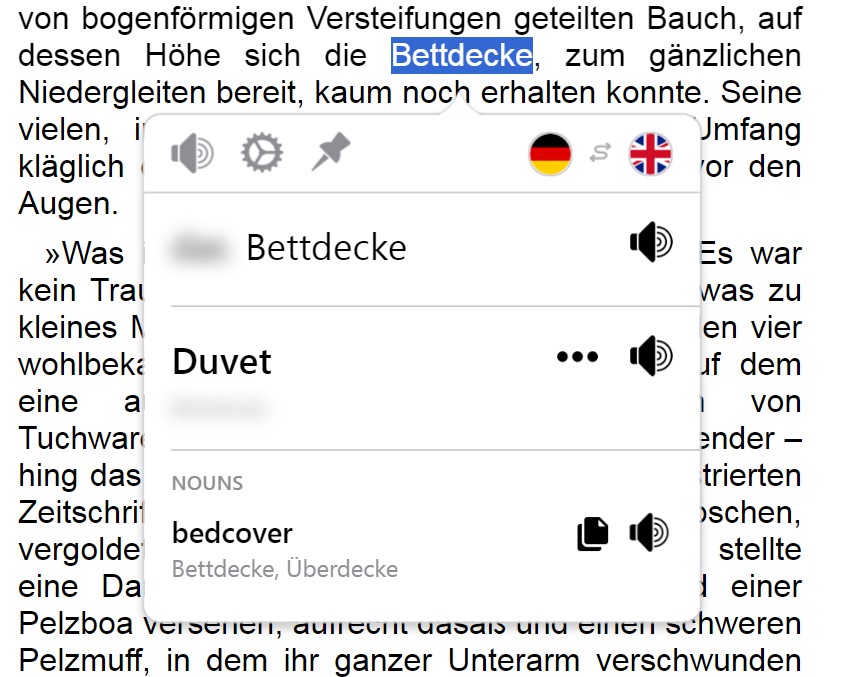

Mate Translate

Next up, let’s look at something a bitmore streamlined, the Mate Translate Extension. There are a bunch of things I like about this extension. First of all, you can get translations very quickly. Double-click a word or phrase, select it, or use a keyboard shortcut. These settings can be customized to your liking.

Also, we get a nicely formatted user-friendly popup, which includes pronunciation and more. Mate Translate can also show articles and phonetic translations but these are locked behind a premium subscription and blurred out for free users:

Pros: fast lookups and customizable shortcuts, user-friendly interface.

Cons: Some advanced features require a premium subscription.

LinguaLeo Language Translator

Next up, we have the LinguaLeo Language Translator Extension. By default it will show translations in a popup after double-clicking a word or phrase. You can also customize it, so the popup will only appear when either holding Alt or Ctrl.

While we don’t get multiple translations, pronunciation audio or additional information about the word, I like that the popup offers you to translate the context in which the word appears. Also, you can add your own translation which can be added to a personalized dictionary for further study, but this requires creating an account.

Pros: fast lookups, basic customization, context translation

Cons: no pronunciation and limited support for ambiguity (translation variety)

ImTranslator

Next up, we have ImTranslator which offers tons of options and customizations and there are no hidden features locked behind premium subscriptions. You can select which translation engine you want to use (Google, Microsoft, Yandex) and customize everything from shortcuts to how the popup appears. My favorite feature here however is that it offers not just popup bubbles, but also in-line translations.

By default, after highlighting a word you can use shortcut ALT+C to show the translation directly in the text, which takes a few seconds but is very nice, since you don’t get distracted by popups:

If you want more information about a word, you can open the popup (either by clicking on the ImTranslator icon [default] or selecting a shortcut or the double-click option). Within the popup you can listen to the pronunciation, check synonyms, etc.

Pros: offers both in-line and popup translations. Tons of customizations. Native dark mode. No premium subscriptions.

Cons: translation can sometimes be a bit slow, UI feels a tad cluttered.

DeepL

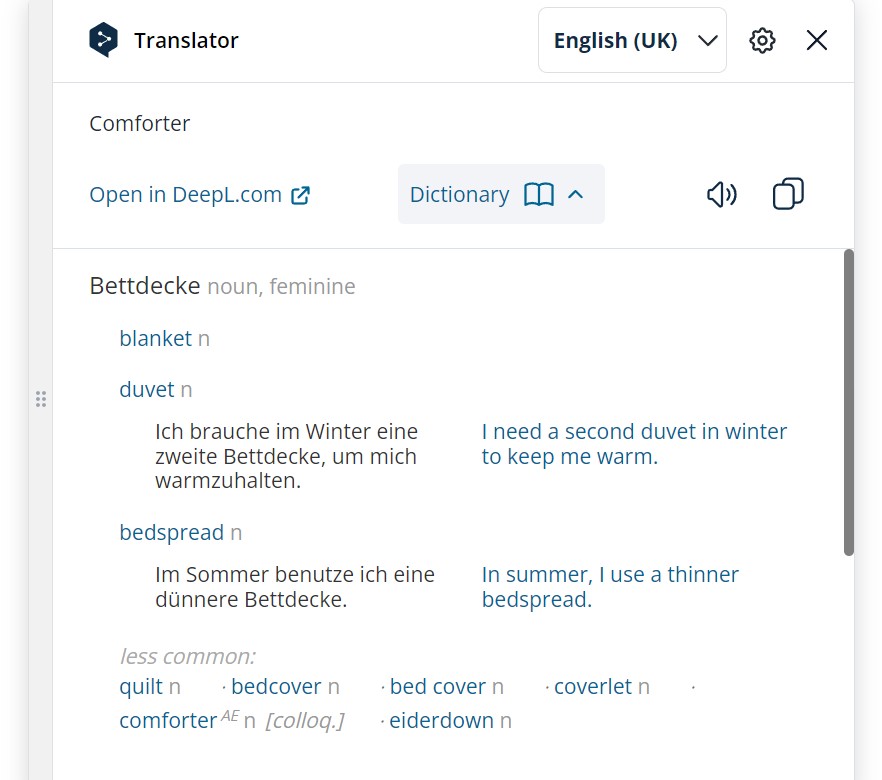

Last but not least, let’s take a look at DeepL’s Chrome extension. Founded in 2017, DeepL has quickly gained a reputation for producing high-quality translations, which many people (including myself) find more accurate and nuanced than some of its competitors, especially when it comes to German.

After installing the extension you can highlight any word or phrase or text on a website, click on the floating DeepL icon (or use the CTRL+Y shortcut) to open the popup. Not only do you get pronunciation audio, but also a very extensive dictionary section with info about the word, e.g. (type of word, genus) and many variations. What I like most here is that all variations come with example sentences plus translations as well.

Also, DeepL offers deep integration into popular services like Gmail, X, Google Docs, WhatsApp, LinkedIn and many others.

Pros: fast and detailed translations with pronunciation plus extensive variations. All for free.

Cons: no double-click translation

Summary

There are many browser extensions that offer on-demand translations for language learners. Personally, DeepL is probably my favorite, both in terms of user-experience and detail of information. What’s yours? Let me know in the comments below!

–

The post Best Browser Extensions to Translate German Words and Phrases Instantly appeared first on LearnOutLive.

NEW: Introducing German Chat Stories For Beginners & Beyond 5 Mar 2024 11:22 AM (last year)

Storytelling can be a powerful way to learn a new language. You easily pick up new words from context, get a natural feel for the rhythm and most importantly, it’s a lot of fun. For a couple of years now, I’ve been experimenting with taking this simple but powerful method my books are based on and adapting it into more interactive and shorter formats.

The first iteration of this idea was the Schlaflose Sarah story which is told in a chat-like format where learners can unfold the story one message at a time, get helpful translation and pronunciation along the way.

The overall response from learners was really positive. People just wanted more stories in this format. So a few weeks ago, I set out to create another story, but when I looked at the underlying code I felt it was time for a complete overhaul.

Read the whole story below or just dive right in:

This latest rendition comes as a progressive web app which is compatible with most systems and browsers (iOS users: look for the “Add to Home screen” button) and is also available on the Google Play Store for Android users.

From Twine To Vanilla JS

I originally created Schlaflose Sarah in Twine, which is a nifty tool for creating non-linear interactive stories, allowing for a lot of customization. But as the project grew in complexity (Tweego is a great compiler for longer projects), I ended up writing a lot of additional code to bend Twine into directions it was never really intended for, which made things generally functional but a bit janky in places.

Besides, I wanted to overhaul a number of core functions anyway, so I went back to the drawing-board and started writing my own “engine” in basic vanilla JavaScript, which seemed a bit daunting at first, but ultimately turned out to be a lot more stable and faster to boot.

After a few weeks of coding, I had a working prototype and started writing a new story within it. The cool thing when you’re both the “content”-writer and the programmer is that you can adapt the code to seamlessly fit the story’s needs and vice versa. This new story had multiple characters for example, so instead of being limited to only one person with one voice, as in my previous project, I simply built a new logic around it.

Dynamic Quizzes

The original app had short text-comprehension quizzes that popped up during the story, along with a simple game-like loop of collecting coins to proceed to the next level.

For this new iteration I wanted to try something a little bit different. Instead of showing every reader the exact same questions, now you will be quizzed based on the actual words and phrases you interacted with, so every “playthrough” will be different.

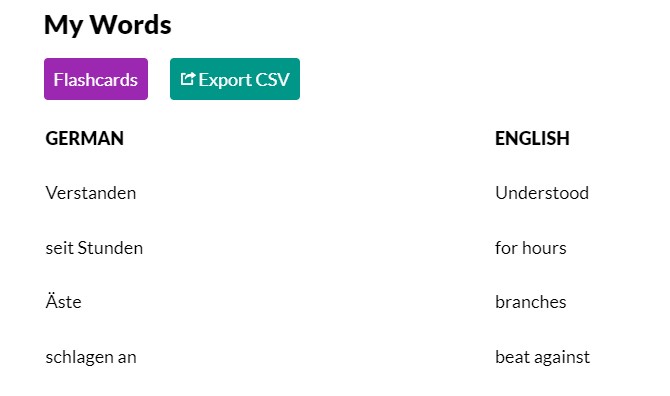

Also, I’ve added user accounts, so you can collect new words, practice with flashcards and even export all your glorious “Wortschatz” (vocabulary, literally: “word treasure”) in CSV format for further use in apps like ANKI or anything else, really.

Voices & Translation

For the original app, I used the latest technology in TTS (text-to-speech) at the time which was Google Cloud TTS. It was much better than the standard robotic voice synthesis we’ve all come to associate with “speaking computers” over the years, but it still sounded somewhat lifeless.

So for this new iteration, I started shopping around again and tested every newfangled TTS-service I could find. Google Cloud TTS had gotten better, but still not great, Amazon Polly was workable but again somewhat dull. Outside of Big Tech, there were numerable other third-party services I tried. But support for German language was often spotty. So in the end I settled on using Elevenlabs for this project, which imho is one of the most life-like of all the TTS models currently out there.

Obviously it’s still not perfect and needs special supervision, especially when dealing with numbers, which it insists to always (!) pronounce in English, so I have to re-create these manually by typing out numbers into full words, e.g. “23” -> “dreiundzwanzig”. Also, I wish there were more fine-grained speed controls, but all in all, I think when looking at models like Elevenlabs it’s pretty clear we’ve come a long way from the robotic “computer speak” à la Fitter Happier.

Apps, Shmapps

The original app was created as a Twine project, then converted to iOS and Android app via Cordova. It was workable, but still very finicky.

Since this was a free app, I eventually grew tired of giving Apple $100 dollars every year for the “privilege” of listing my free app on their store, and I took it down.

As an alternative I simply made the whole thing available as a progressive web app, allowing people to either enjoy it in their browser or “add to home screen”.

This time around, I’m going the opposite route, starting with a web-first approach, i.e. everything is designed from the ground up as a progressive web app which then can can be easily re-packaged and shipped to Android, etc.

IOS remains an ongoing concern, but shipping to Android was easily done in a few hours and you can get the result here.

About The Stories

So far, I’ve released a complete new story which is a fun new twist on Little Red Riding Hood titled Rotkäppchen Reloaded. Also, I’ve ported Schlaflose Sarah over to the new “engine” so you can enjoy it with the new voices, quizzes etc.

Needless to say, both of these are a bit … weird, like many of my stories. It has always been my humble conviction that life is too short for generic language learning texts. Why not have a bit of fun instead? So yeah, don’t expect tons of dull AI-generated nonsense anytime soon. This is all 100% purely hand-crafted human nonsense!

When it comes to new stories, I already have a bunch of ideas, one almost finished (*checks list* – yes, pretty weird, as well). You can turn on notifications in the app or join my newsletter to get an update when the next one is ready.

Features & Bugs

Since I released this new app on my newsletter I’ve received many helpful suggestions for features, bug reports, etc. And the overall experience has matured quite a bit since then. There’s now an auto-playback feature for passively listening to messages, “savegame” logic, opt-in (!) push and email notifications, a little tutorial for new users, and a bunch of other little tweaks.

If you have any suggestions for new features, bug reports, etc. please feel free to leave a comment below.

–

The post NEW: Introducing German Chat Stories For Beginners & Beyond appeared first on LearnOutLive.

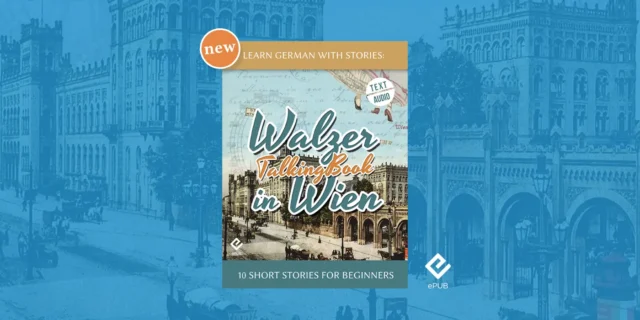

NEW: Walzer in Wien TalkingBook + Free Demo 26 Jan 2024 5:29 AM (last year)

Good news everyone! There’s a new TalkingBook edition for Walzer in Wien, episode 7 of the Dino lernt Deutsch series, with completely remastered audio narration.

As usual I’ve also added this TalkingBook to the Walzer in Wien ebook and audio bundle, and the Dino Complete Series Bundle, so if you purchased either of these bundles from our store in the past you get automatic access.

What Is A TalkingBook?

Learning a language is a process with many moving parts. There’s speaking practice, reading practice, writing practice, grammar practice, etc.

Studies have shown that learners progress best when combining multiple modalities.

TalkingBooks are my humble invitation to combine reading and listening practice, so that you can immediately see what you’re hearing and vice versa.

You can either lean back, listen to the audio and watch the text being highlighted for you, or hone in on specific phrases for pronunciation practice, etc.

If you’ve never tried this simple but powerful approach to language learning before, I’ve set up a little demo that finally allows anyone interested to see it in action without having to register or download anything:

–

The post NEW: Walzer in Wien TalkingBook + Free Demo appeared first on LearnOutLive.

Die Küchenuhr – Wolfgang Borchert (1921-1947) 10 Nov 2023 4:47 AM (2 years ago)

Introduction

“Die Küchenuhr” (The Kitchen Clock), first published in 1947, is a popular short story by the renowned German writer Wolfgang Borchert (1921-1947), known for his powerful works that capture the profound impact of war on individuals and society. Borchert himself was deeply affected by his experiences as a soldier in World War II and used his writing to express the disillusionment and suffering of his times.

This short story is perhaps one of the most famous examples of the Trümmerliteratur (rubble literature) movement, a literary trend that emerged in Germany in the years following WWII. This literary movement was characterized by its focus on the destruction and devastation of the war, and the desperate search for meaning and identity in its aftermath, not just on a psychological but also on a deeper cultural level.

After the war Germany’s cities lay in ruins, just like its literature and language which had been twisted and weaponized under the Nazi regime. Writers like Borchert felt they had to start from zero, which is why this literary genre is also often called “Stunde Null” (zero hour) literature.

“Wir brauchen keine Dichter mit guter Grammatik. Zu guter Grammatik fehlt uns Geduld.” – We don’t need poets with good grammar. We don’t have the patience for good grammar. – Wolfgang Borchert

Borchert’s narrative style is characterized by its minimalist and evocative prose and was influenced by literary ideas like Hemingway’s Iceberg theory.

This is an approach where the author only presents the tip of the iceberg (the visible part) while leaving much of the story’s meaning and details hidden beneath the surface. In simple terms, it means that the author often doesn’t spell out everything explicitly. Instead, she gives readers just enough information to understand the story, but leaves many things unsaid, allowing readers to infer and imagine the deeper, unspoken meanings and emotions.

Not only does this approach allow readers to actively engage with the text by filling in the gaps with their own interpretations and emotions, but it also uses a somewhat limited vocabulary and minimal grammatical complexity which makes this genre an excellent starting point for German learners who want to delve into the world of German literature.

Below you’ll find the complete text of the original short story by Borchert, including in-line translation for key words and phrases (tap or hover over underlined words to see the English translation), and an excellent audio recording by Florens Schmidt (via vorleser.net) to follow along.

Die Küchenuhr – “The Kitchen Clock”

Sie sahen ihn schon von weitem auf sich zukommen, denn er fiel auf. Er hatte ein ganz altes Gesicht, aber wie er ging, daran sah man, dass er erst zwanzig war. Er setzte sich mit seinem alten Gesicht zu ihnen auf die Bank. Und dann zeigte er ihnen, was er in der Hand trug.

“Das war unsere Küchenuhr“, sagte er und sah sie alle der Reihe nach an, die auf der Bank in der Sonne saßen. “Ja, ich habe sie noch gefunden. Sie ist übriggeblieben.”

Er hielt eine runde tellerweiße Küchenuhr vor sich hin und tupfte mit dem Finger die blaugemalten Zahlen ab.

“Sie hat weiter keinen Wert,” meinte er entschuldigend, “das weiß ich auch. Und sie ist auch nicht so besonders schön. Sie ist nur wie ein Teller, so mit weißem Lack. Aber die blauen Zahlen sehen doch ganz hübsch aus, finde ich. Die Zeiger sind natürlich nur aus Blech. Und nun gehen sie auch nicht mehr. Nein. Innerlich ist sie kaputt, das steht fest. Aber sie sieht noch aus wie immer. Auch wenn sie jetzt nicht mehr geht.”

Er machte mit der Fingerspitze einen vorsichtigen Kreis auf dem Rand der Telleruhr entlang. Und er sagte leise: “Und sie ist übriggeblieben.”

Die auf der Bank in der Sonne saßen, sahen ihn nicht an. Einer sah auf seine Schuhe und die Frau sah in ihren Kinderwagen. Dann sagte jemand:

“Sie haben wohl alles verloren?”

“Ja, ja”, sagte er freudig, “denken Sie, aber auch alles! Nur sie hier, sie ist übrig.” Und er hob die Uhr wieder hoch, als ob die anderen sie noch nicht kannten.

“Aber sie geht doch nicht mehr”, sagte die Frau.

“Nein, nein, das nicht. Kaputt ist sie, das weiß ich wohl. Aber sonst ist sie doch noch ganz wie immer: weiß und blau.” Und wieder zeigte er ihnen seine Uhr. “Und was das Schönste ist”, fuhr er aufgeregt fort, “das habe ich Ihnen ja noch überhaupt nicht erzählt. Das Schönste kommt nämlich noch: Denken Sie mal, sie ist um halb drei stehengeblieben. Ausgerechnet um halb drei, denken Sie mal.”

“Dann wurde Ihr Haus sicher um halb drei getroffen“, sagte der Mann und schob wichtig die Unterlippe vor. “Das habe ich schon oft gehört. Wenn die Bombe runtergeht, bleiben die Uhren stehen. Das kommt von dem Druck.”

Er sah seine Uhr an und schüttelte überlegen den Kopf. “Nein, lieber Herr, nein, da irren Sie sich. Das hat mit den Bomben nichts zu tun. Sie müssen nicht immer von den Bomben reden. Nein. Um halb drei war ganz etwas anderes, das wissen Sie nur nicht. Das ist nämlich der Witz, dass sie gerade um halb drei stehengeblieben ist. Und nicht um viertel nach vier oder um sieben. Um halb drei kam ich nämlich immer nach Hause. Nachts, meine ich. Fast immer um halb drei. Das ist ja gerade der Witz.”

Er sah die anderen an, aber die hatten ihre Augen von ihm weggenommen. Er fand sie nicht. Da nickte er seiner Uhr zu: “Dann hatte ich natürlich Hunger, nicht wahr? Und ich ging immer gleich in die Küche. Da war es dann fast immer halb drei. Und dann, dann kam nämlich meine Mutter. Ich konnte noch so leise die Tür aufmachen, sie hat mich immer gehört. Und wenn ich in der dunklen Küche etwas zu essen suchte, ging plötzlich das Licht an. Dann stand sie da in ihrer Wolljacke und mit einem roten Schal um. Und barfuß. Immer barfuß. Und dabei war unsere Küche gekachelt. Und sie machte ihre Augen ganz klein, weil ihr das Licht so hell war. Denn sie hatte ja schon geschlafen. Es war ja Nacht.

So spät wieder, sagte sie dann. Mehr sagte sie nie. Nur: So spät wieder. Und dann machte sie mir das Abendbrot warm und sah zu, wie ich aß. Dabei scheuerte sie immer die Füße aneinander, weil die Kacheln so kalt waren. Schuhe zog sie nachts nie an. Und sie saß so lange bei mir, bis ich satt war. Und dann hörte ich sie noch die Teller wegsetzen, wenn ich in meinem Zimmer schon das Licht ausgemacht hatte. Jede Nacht war es so. Und meistens immer um halb drei. Das war ganz selbstverständlich, fand ich, dass sie mir nachts um halb drei in der Küche das Essen machte. Ich fand das ganz selbstverständlich. Sie tat das ja immer. Und sie hat nie mehr gesagt als: So spät wieder. Aber das sagte sie jedes Mal. Und ich dachte, das könnte nie aufhören. Es war mir so selbstverständlich. Das alles war doch immer so gewesen.”

Einen Atemzug lang war es ganz still auf der Bank. Dann sagte er leise: “Und jetzt?” Er sah die anderen an. Aber er fand sie nicht. Da sagte er der Uhr leise ins weißblaue runde Gesicht: “Jetzt, jetzt weiß ich, dass es das Paradies war. Das richtige Paradies.”

Auf der Bank war es ganz still. Dann fragte die Frau: “Und Ihre Familie?”

Er lächelte sie verlegen an: “Ach, Sie meinen meine Eltern? Ja, die sind auch mit weg. Alles ist weg. Alles, stellen Sie sich vor. Alles weg.”

Er lächelte verlegen von einem zum anderen. Aber sie sahen ihn nicht an.

Da hob er wieder die Uhr hoch und er lachte. Er lachte: “Nur sie hier. Sie ist übrig. Und das Schönste ist ja, dass sie ausgerechnet um halb drei stehengeblieben ist. Ausgerechnet um halb drei.”

Dann sagte er nichts mehr. Aber er hatte ein ganz altes Gesicht. Und der Mann, der neben ihm saß, sah auf seine Schuhe. Aber er sah seine Schuhe nicht. Er dachte immerzu an das Wort Paradies.

~

Vocabulary

Discussion

The following questions can be used to further discussions and conversations, either in class or during self-study:

- Who is the protagonist of the story, and what is their primary concern?

- Describe the significance of the kitchen clock in the story. How does it symbolize a central theme?

- What is the setting of the story, and how does it contribute to the overall atmosphere and mood?

- How does the story depict the impact of war on the characters, particularly the protagonist?

- Discuss the relationship between the protagonist and the kitchen clock. What does it reveal about the character’s emotional state?

- What role do the other characters in the story play, and how do they interact with the protagonist?

- Explain the importance of the narrative style and language used by the author in conveying the story’s themes and emotions.

- What does the ending of the story suggest about the protagonist’s state of mind and the overall message of the narrative?

- How does “Die Küchenuhr” fit into the context of Trümmerliteratur (rubble literature) and the post-World War II period in Germany?

- What emotions or ideas do you think the author wants readers to take away from the story, and why?

Notes

I added dialogue tags (in double quotes) to indicate direct speech where the original text omitted them. Also I corrected the spelling to conform with modern German orthography reform, e.g. daß -> dass, jedesmal -> jedes Mal, etc.

Credits

Copyright of original text: public domain (since 2018)

Narration: vorleser.net, Florens Schmidt

Translation & code: André Klein

–

The post Die Küchenuhr – Wolfgang Borchert (1921-1947) appeared first on LearnOutLive.

New Release: Sturm auf Sylt Audiobook (MP3) 27 Oct 2023 12:41 AM (2 years ago)

I know many of you have been waiting for this, so I’m very happy to announce that the audiobook for Dino lernt Deutsch, episode 12: Sturm auf Sylt is finally here!

Like all Dino lernt Deutsch audiobooks, this one comes in high quality MP3* format, to enjoy on any device or app you prefer, without limitations, walled gardens and other shenanigans. (Apple Books and Audible editions will follow soon.)

(If you don’t have the ebook yet, there’s also a bunch of new bundle offers.)

–

*Did you know that the MP3 format was invented in Germany?

The post New Release: Sturm auf Sylt Audiobook (MP3) appeared first on LearnOutLive.

4 Ways How Reading In German Can Improve Your Speaking Proficiency 13 Sep 2023 4:23 AM (2 years ago)

Reading German novels or short stories can be a great way to increase your vocabulary and see grammatical structures in action. There’s no pressure to parse things quickly. You can take your time with each sentence or paragraph until you feel confident you’ve understood everything.

But is reading foreign language “comprehensible input” only helpful for improving your passive (comprehension) skills, or can it actually improve your active (production) skills?

While there are good studies [1] [2] on the effectiveness of the former, it seems that the impact of extensive reading on productive skills (specifically speaking) is still under-researched.

In my own experience, reading novels in English has been extremely helpful for developing my speaking and writing abilities. And it seems that many people experience a similar effect.

For example, yesterday I stumbled over an interesting blog post by Juan Francisco in which he writes:

I remember one occasion when, after months of private German lessons, I finally decided to take the challenge of reading Kafka’s Metamorphosis in the original. In those days I read at night, with a dim lamp and an uncomfortable chair. It took me two hours to get through ten pages. It was a kind of torture, very much in tune with the story of Gregor Samsa, but I was thoroughly enjoying it. The following week I went to class with my teacher and, after fifteen minutes of conversation, she interrupted me: “You’re speaking very well! What did you do?”. I hadn’t done any more exercises, any more homework, I hadn’t practiced my verbs or gone through my vocabulary lists, I had been reading Kafka.

As an author of simple stories for German learners, I often receive similar feedback from readers, telling me how immersing themselves in German storytelling has helped them become better not only at understanding texts, but also in their speaking proficiency.

And while most of the “evidence” here is purely anecdotal, I do think there are a number of good reasons why reading can indeed boost your speaking skills.

1. Vocab Bonanza

First of all, reading exposes you to a wide range of vocabulary, including colloquial expressions and idiomatic phrases used in everyday conversations. This is especially true for contemporary novels and short stories that use a lot of dialogue or are written in a colloquial style, for example from the perspective of a first-person narrator.

Over time, this expanded vocabulary can become part of your active Wortschatz (treasury of words). This doesn’t happen overnight, in my experience, but small consistent efforts compound over time and new vocabulary will slowly seep from passive into active proficiency.

This process can be greatly amplified when using spaced-repetition methods to commit new words to long-term memory.

2. Grammar Galore

By reading German novels, you become familiar with sentence structures, tenses, and other grammatical constructions used in real-life contexts. This exposure can drastically improve your understanding of how sentences are formed in German, decreasing the time it may take you to put your own sentences together when speaking.

In short, when you’ve been exposed to tons of examples of grammatically correct input you start to develop a feel for the right word order, tenses, etc. and the constant second-guessing will slowly make way for clear and confident speech.

3. Context is King

Stories and novels provide you with real-world context in which words and phrases are used. This contextual understanding is crucial for using vocabulary and grammar correctly in spoken communication.

Many words have multiple meanings and connotations in any language. Stories are filled with examples of how words can have nuanced meanings depending on the situation. Understanding these subtleties goes a long way in expressing yourself more precisely in conversations.

German modal particles for example are notoriously hard to grasp for learners. By getting a feel for how and when these little words are used in dialogues, it’ll become a lot easier to mimic correct usage when speaking.

Last but not least, context in literature often reflects cultural norms, customs, and social interactions. Understanding these cultural subtleties is crucial for effective communication. For instance, knowing when and how to use the German Sie vs Du (formal vs. informal) is deeply rooted in cultural context.

4. Mastering the Melody

Last but not least, when you read literature in German, you’re not just absorbing vocabulary and grammar; you’re also immersing yourself in the musicality of the language—the way it sounds, its rhythm, pronunciation, and intonation patterns. This auditory exposure, even in silent reading (!), plays a pivotal role in enhancing your spoken language skills.

How does it work exactly? There’s some debate about it, but I think a lot of it has to do with the “inner voice” or internal dialogue we experience in our own heads.

Fore more about this, check out this excellent Radiolab episode that discusses some theories about the role of this internal dialogue in language acquisition (and beyond).

–

The post 4 Ways How Reading In German Can Improve Your Speaking Proficiency appeared first on LearnOutLive.

German Sayings & Proverbs Quiz 23 May 2023 5:53 AM (2 years ago)

Proverbs and sayings play a significant role in German culture, reflecting the wisdom, humor (yes, it exists), and values of the culture. These concise and often poetic expressions provide insights into German customs, beliefs, and everyday life.

Whether you’re a language enthusiast, a traveler, or simply curious about German culture, this quiz will put your knowledge to the test.

So, if you’re ready to embark on a linguistic and cultural journey through the German-speaking world, get ready to match the proverbs with their meanings, decipher their hidden messages, and discover the fascinating cultural insights behind these age-old sayings.

Viel Erfolg! (Good luck!)

1. What is the meaning of the saying “Aller Anfang ist schwer”?

A. [question][All good things come to those who wait.]

B. [correct][Every beginning is difficult.]

C. [question][Actions speak louder than words.]

[ANSWER][This proverb emphasizes the challenges that come with starting something new.]

2. “Wer A sagt, muss auch B sagen” translates to:

A. [question][Better late than never.]

B. [question][Don’t judge a book by its cover.]

C. [correct][If you start something, you should finish it.]

[ANSWER][Literally meaning “If you say A, you also have to say B”, this saying highlights the importance of following through with commitments and responsibilities.]

3. What is the German equivalent of the English saying “The early bird catches the worm”?

A. [correct][Der frühe Vogel fängt den Wurm.]

B. [question][Wer zuerst kommt, mahlt zuerst.]

C. [question][Morgenstund hat Gold im Mund.]

[ANSWER][These two sayings are exactly the same in German and English.]

4. “Ein Unglück kommt selten allein” means:

A. [question][Every cloud has a silver lining.]

B. [question][Practice makes perfect.]

C. [correct][Misfortunes rarely come alone.]

[ANSWER][It suggests that when something unfortunate happens, it is often followed by more difficulties or challenges.]

5. What is the German equivalent of the proverb “Actions speak louder than words”?

A. [correct][Taten sagen mehr als Worte.]

B. [question][Lügen haben kurze Beine.]

C. [question][Aller Anfang ist schwer.]

[ANSWER][Literally translated it means: “deeds say more than words”.]

6. What’s the German saying for “adding an unsolicited comment?”

A. [question][jemandem auf den Senkel gehen]

B. [correct][seinen Senf dazugeben]

C. [question][einen Sockenschuss haben]

[ANSWER][Literally it means “adding one’s mustard”. This expression is believed to have originated in the 17th century. During that time, mustard was considered a spice that made any meal more enjoyable, even if it didn’t necessarily go with it. All the hosts of that era, whether desired or not, simply served mustard to their guests with every dish. Since this was as unpleasant as unsolicited advice, over time the proverb “to add one’s mustard” became established.]

7. What is the German equivalent of the saying “Better late than never”?

A. [correct][Besser spät als nie]

B. [question][Der frühe Vogel fängt den Wurm]

C. [question][Was lange währt, wird endlich gut]

[ANSWER][]

8. What is the meaning of giving someone a “Wink mit dem Zaunpfahl” (wave with a fence post)?

A. [question][giving someone bad advice]

B. [question][giving someone a big compliment]

C. [correct][giving someone an obvious hint.]

[ANSWER][The underlying idea is that the fence post is so large that waving it cannot go unnoticed. So giving someone a “Wink mit dem Zaunpfahl” means giving someone an obvious hint.]

9. What is “Dicke Luft” (thick air)?

A. [question][a light and uplifting atmosphere]

B. [correct][a gloomy or oppressive atmosphere]

C. [question][an inaccurate weather report]

[ANSWER][It refers to the density of the atmosphere, as compressed air can escape explosively. For example when you enter a room while two people are arguing you may be entering an atmosphere of “dicke Luft”.]

10. When something is broken or failed, it is …

A. [correct][im Eimer]

B. [question][im Eisfach]

C. [question][im Kasten]

[ANSWER][It is broken, gone awry, a mess. It has (figuratively as well as literally) ended up in the trash bin (Mülleimer).]

11. In German we don’t have mnemonic devices, but we build …

A. [question][skewed steeples]

B. [correct][donkey bridges]

C. [question][donkey gates]

[ANSWER][“Eine Eselsbrücke bauen” literally means “building a donkey bridge” and it refers to making mnemonic devices. Why? Donkeys are generally averse to water and reluctant to cross even small streams as they can’t gauge the depth. Therefore, historically, small bridges were built for the animals, saving time and avoiding detours. Similarly, mnemonic devices can help us avoid detours of forgetfulness and memorize information faster.]

12. What’s the German equivalent of “comparing apples and oranges”?

A. [correct][Äpfel und Birnen vergleichen]

B. [question][Bananen und Birnen vergleichen]

C. [question][Äpfel und Tomaten vergleichen]

[ANSWER][When you compare “apples and pears” in German you are drawing comparisons between incomparable things.]

The post German Sayings & Proverbs Quiz appeared first on LearnOutLive.