Aging Populations and Regional Economic Development 29 Mar 6:03 PM (8 days ago)

Aging Populations and Regional Economic Development:

Insights from the 2025 NADO & DDAA Washington Conference

Population aging is rapidly transforming regions across the country and increasing the need for, and diversity of, support programs for older adults and their caregivers. At the 2025 NADO Washington Policy Conference, a session titled Aging and RDOs: What’s Changing and What’s Ahead brought together experts to discuss how Regional Development Organizations (RDOs) and Economic Development Districts (EDDs) can adapt to these shifts. The panel featured Annette Gutierrez, Executive Director of the Rio Grande Council of Governments, Sandy Markwood, CEO of USAging, and Brendan Flinn, Director of Long-Term Services and Supports at the AARP Public Policy Institute. Each offered a unique perspective on aging trends, policy implications, and strategies for integrating aging into economic development planning. Their insights underscored both the challenges and opportunities associated with an aging society, particularly for regional leaders working to support economic resilience and social well-being.

Many RDOs function as Area Agencies on Aging (AAA) for their regions or work closely with their region’s AAA. Moreover, aging is increasingly recognized as a major topic for regional economic developers. The recent NADO publication Older Adults and Economic Development: Planning for an Aging Population discusses this trend and includes tips for including aging as a topic in the CEDS and other planning efforts.

Key Takeaways

- Demographic and Economic Trends in Aging

The panelists highlighted the rising costs of aging-related services, noting that home care and nursing home care are becoming increasingly unaffordable due to inflation and workforce shortages. AARP research has found that the cost of home care has risen faster than other major expenses like food and energy, posing a significant financial challenge for families.

On a positive note, there is growing recognition of the role of social care alongside medical care. The panelists emphasized that most healthcare occurs not in hospitals but in homes and communities. Networks of AAAs are expanding services to address care transitions, home care, nutrition, and transportation. Additionally, multisector state aging plans are bringing together diverse stakeholders, including economic development professionals, to address aging as a broad societal issue. Panelists recommended that RDOs and AAAs get involved with these state planning processes.

However, challenges persist, including social isolation among older adults and caregivers, as well as funding gaps for services.

Gutierrez shared that her region is struggling with a wages/services challenge: paying higher wages makes it easier to hire care workers, but reduces the number of people her programs can serve. She also noted a shift toward seeking support from localities and philanthropic organizations to fill funding gaps and recommended that attendees consider similar approaches.

- Policy and Funding: The Future of the Older Americans Act (OAA)

One major topic was the ongoing efforts to reauthorize the Older Americans Act (OAA), a crucial source of federal funding for aging services. Markwood outlined several key wins that could come out of reauthorization, including streamlined contracting processes for AAAs, an expansion of evidence-informed programs, codification of grab-and-go meal programs, and increased funding levels for five years. However, she emphasized that it is a significant concern that the act is not currently authorized. She urged attendees to share stories with policymakers that demonstrate the critical role the OAA plays in supporting communities.

Gutierrez emphasized that aging policy affects everyone—not just older adults today, but also their caregivers and communities, as well as future generations who will face these same challenges.

- Preparing for Potential Funding Cuts: Strategies from the Field

Given potential funding uncertainties, the panelists discussed proactive strategies for maintaining essential aging services. As mentioned previously, Gutierrez shared that her organization is strengthening partnerships with local governments, nonprofit funders, and healthcare providers to diversify financial support. Exploring private pay models and innovative contracting mechanisms are also key strategies.

Should funding cuts materialize, panelists emphasized, prioritizing essential programs—such as meal delivery services—is critical to safeguarding support for the most vulnerable older adults.

- Integration of Aging Issues into Economic Development

The discussion underscored the importance of breaking down silos between aging services, economic development, and other sectors. Older adults interact with a range of systems—including transit, housing, and workforce development—which must be better coordinated to meet their needs.

Housing was identified as a particularly pressing issue, with Markwood noting that adults over 50 are the fastest-growing segment of the homeless population. Economic development strategies must include efforts to keep older adults engaged in the workforce, whether through flexible employment options, reskilling programs, or entrepreneurship support.

Flinn also emphasized that state and local leadership play a vital role in integrating aging into broader planning efforts. States with multisector aging plans are making significant progress, and local governments should follow suit by convening cross-sector discussions on aging. As natural conveners, RDOs and EDDs are well-positioned to participate in those discussions.

- Workforce Challenges and Innovations

While Rio Grande COG has not experienced a mass exodus of workers post-COVID, workforce retention remains an ongoing challenge due to pay disparities and job demands. Gutierrez highlighted strategies such as building relationships with university social work programs, strengthening ties with workforce development organizations, and advocating for state policy changes that support wage increases as potential solutions for workforce challenges.

Markwood pointed to an innovative model from Michigan where an emergency fund for direct care workers reduced absenteeism by 80%, illustrating how strategic investments can improve workforce stability.

- Supporting Caregivers

Caregivers provide an estimated $600 billion in unpaid care annually in the U.S., making them a critical yet often under-supported component of the aging services ecosystem. Markwood pointed out that live-in caregivers provide an average of 40 hours of care per week, while those who live separately contribute around 20 hours. The National Family Caregiver Support Program—administered by AAAs—is severely underfunded, despite being the only large-scale federal program dedicated to caregivers.

Both Markwood and Flinn emphasized the importance of advocating for increased funding and exploring policy solutions such as caregiver tax credits. Educating caregivers about available services before they reach a crisis point is another key priority.

- New Ideas and Innovative Programs

The session concluded with a discussion of emerging models and innovative solutions in aging services. Gutierrez again encouraged RDOs and AAAs to explore partnerships with non-traditional interests as a means of securing additional funding. One example shared was a collaboration between an AAA and a local restaurant to provide meal services in areas without existing congregate meal facilities.

Flinn highlighted a new Medicare policy that allows Part D clinicians to be reimbursed for training caregivers—a promising but underutilized opportunity. Markwood shared examples of efficiency-focused initiatives, such as Oregon and Massachusetts’ statewide coordination of evidence-based programs, which enable rural AAAs to share resources rather than duplicating efforts. Michigan’s centralized longevity services center, created through partnerships between universities and nonprofits, was another successful model.

Conclusion

Aging is no longer a niche issue—it is a defining challenge for regional economies and community development. The insights from this conference session reinforced the need for RDOs to take an active role in integrating aging into economic and workforce planning. Policymakers, funders, and practitioners must work together to ensure that aging services remain financially sustainable and responsive to evolving needs.

One major theme from the session was the importance of advocacy. As the policy landscape evolves, RDOs should continue to communicate the value of the Older Americans Act and related programs to legislators, making aging issues tangible and relevant to decision-makers. By fostering partnerships, embracing innovation, and elevating the conversation around aging, communities can create more inclusive and resilient economies for all generations.

For more information, contact NADO Program Manager Dion Thompson-Davoli

The post Aging Populations and Regional Economic Development appeared first on NADO.

Enhancing CEDS with Wealth Creation Strategies 27 Mar 6:32 AM (10 days ago)

Building Prosperity:

How EDDs are Enhancing CEDS with Wealth Creation Strategies

Wealth creation is a community-centered, systems approach to community and economic development that applies a distinctive lens to asset-based development. Wealth creation uses a value chain approach to connect the community’s existing assets with new market opportunities to build wealth and create livelihoods that are rooted locally. The focus is on supporting local ownership and building on existing assets to strengthen and grow the local economy.

Wealth creation allows communities to focus on what they have— instead of what they lack—to generate new and sustainable economic opportunities that are rooted in local people, places and businesses.

This framework supports and builds upon existing economic development programs like the Comprehensive Economic Development Strategies (CEDS), while allowing a more refined and local approach to economic development planning that ensures that the capacity and resources generated by the plan stay in the community.

The strength of the wealth creation approach is in its inherent flexibility.

The Keys to Wealth Creation

1. Recognize and build multiple forms of wealth.

2. Promote local ownership and control of assets.

3. Improve livelihoods for those currently living on the economic and social margins.

Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy

According to the US Economic Development Administration (EDA), “The Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) contributes to effective economic development in America’s communities and regions through a place-based, regionally driven economic development planning process.” In recent years, Economic Development Districts (EDDs) have included wealth creation strategies in their CEDS to ensure long-term, generational benefits for communities, moving beyond traditional economic growth towards more sustainable and wide-ranging prosperity. EDDs have incorporated wealth creation into the CEDS by:

Fostering Asset-Based Economic Development by Leveraging Local Assets and Community-Owned Wealth. EDDs identify unique local resources, such as natural landscapes, cultural heritage, or industrial capabilities, on which to build opportunities. EDDs promote structures of local ownership and control of assets through cooperatives, employee-owned businesses, or land trusts that keep wealth within the community.

Encouraging Local and Regional Entrepreneurship Through Support for Small Businesses, Social Enterprises, and Anchor Institutions. EDDs can offer initiatives such as microloans, technical assistance, and incubators for local entrepreneurs. Some EDDs promote business opportunities that combine profit-making with addressing community challenges. EDDs often leverage hospitals, universities, and large regional employers to support local procurement and entrepreneurship.

Enhancing Capital Access through Innovative Financing Tools and Public Infrastructure Projects. EDDs facilitate revolving loan funds, public-private partnerships, and opportunities to attract investment while maintaining community control. Through support for investments in transportation, broadband, and utilities, EDDs can lower costs and enable economic participation.

Measuring Wealth Creation Beyond Jobs: EDDs can evaluate success through metrics such as income growth, different kinds of wealth retained locally, and economic mobility.

Incorporating Wealth Creation into the CEDS

Process

Wealth creation is an important lens through which to view the CEDS content as well as the CEDS process. The CEDS planning process offers a useful opportunity to engage a diverse group of stakeholders in taking stock of what’s happening on the ground locally and imagining what could be. EDA recommends a variety of steps:

1. Establish and maintain a CEDS Strategy Committee.

2. Define the Strategy Committee’s roles and relationships.

3. Leverage staff resources.

4. Adopt a program of work.

5. Seek stakeholder input on an initial CEDS document.

6. Finalize CEDS document including stakeholder input.

7. Submit a CEDS Annual Performance Report.

8. Revise/update the CEDS (at least every five years).

There are many ways to incorporate wealth creation principles and strategies into the CEDS planning process. For example, engaging the CEDS Strategy Committee and other stakeholders can be an important first step:

- Multiple Forms of Wealth. One way to think about the CEDS Strategy Committee through a wealth creation lens is to consider stakeholders with strengths around building different forms of wealth.

- Dignity and Respect. Another way to think about stakeholders is to include people and organizations that can represent the entire socio-economic spectrum.

EDDs engage stakeholders in different ways. For example, the Acadiana Planning Commission in Louisiana held three CEDS Strategy Meetings, including one on the successes of the region’s economic development activities; one for the SWOT Analysis, which incorporated the eight capitals; and one for Future Goals, Objectives, and Strategies of the Region.

Region Five Development Commission (R5DC), an EDD based in Staples, Minnesota, engages CEDS stakeholders based on their strengths in building specific capitals. See the CEDS Strategy Committee to the right, noting the “Economic Interest by WealthWorks capital” column. R5DC calls its version a Comprehensive Regional Economic Development Strategy or CREDS.

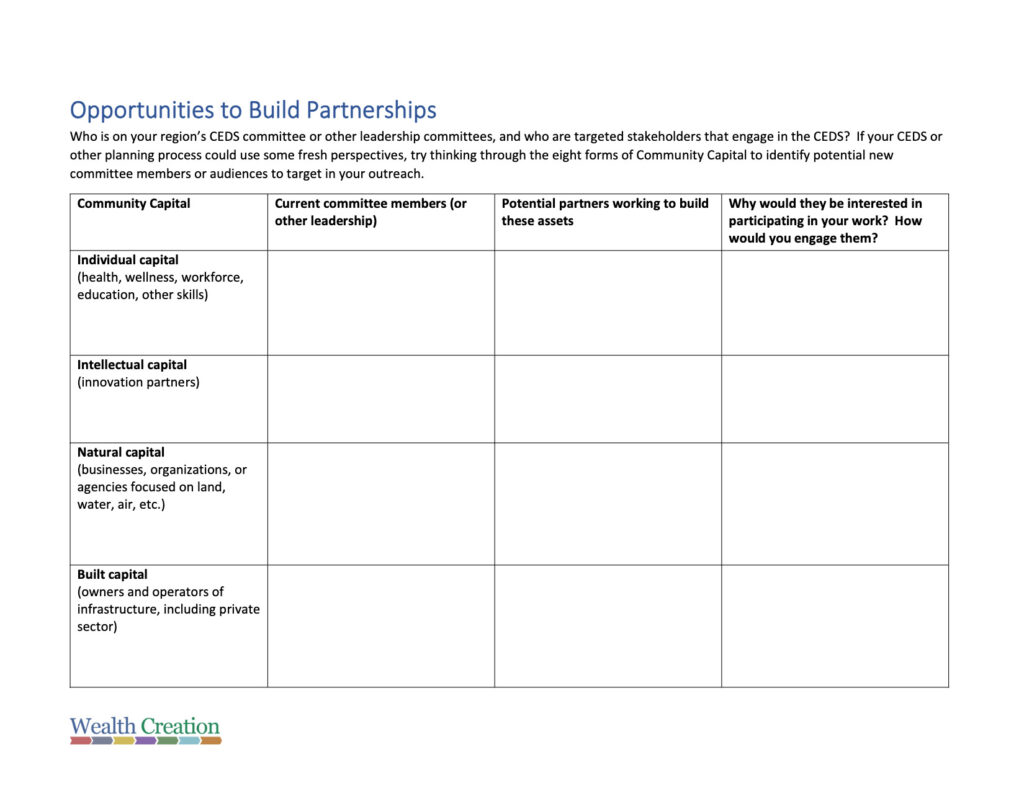

Find the Opportunities to Build Partnerships worksheet on the NADO Wealth Creation microsite and below. This worksheet provides an opportunity to consider current and future CEDS Committee members based on their strengths in building different regional and community capitals, as well as the value propositions, messages, and methods to use in engaging them.

Another resource to explore is NADO RF’s How to Build the CEDS Strategy Committee brief.

Incorporating Wealth Creation into the CEDS

Content

Each of the required sections of the CEDS provides an opportunity to incorporate wealth creation concepts and approaches. The sections are briefly summarized below:

- Summary Background: A summary background of the economic conditions of the region.

- SWOT Analysis: An in-depth analysis of regional strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (commonly known as a “SWOT” analysis).

- Strategic Direction/Action Plan: The strategic direction and action plan should build on findings from the SWOT analysis and incorporate/integrate elements from other regional plans (e.g., land use and transportation, workforce development, etc.) where appropriate as determined by the EDD or community/region engaged in development of the CEDS. The action plan should also identify the stakeholder(s) responsible for implementation, timetables, and opportunities for the integrated use of other local, state, and federal funds.

- Evaluation Framework: Performance measures used to evaluate the organization’s implementation of the CEDS and impact on the regional economy.

This is a summary background of the economic conditions of the region. The question to be answered here is “What have we done?” and “What is going on in our region?”

The opportunity here is to report the conditions of the region across the eight capitals. This might include the obvious ones: jobs and employment, educational attainment, revenues, income. But it may also include conditions of natural capital, cultural capital, intellectual capital, and more.

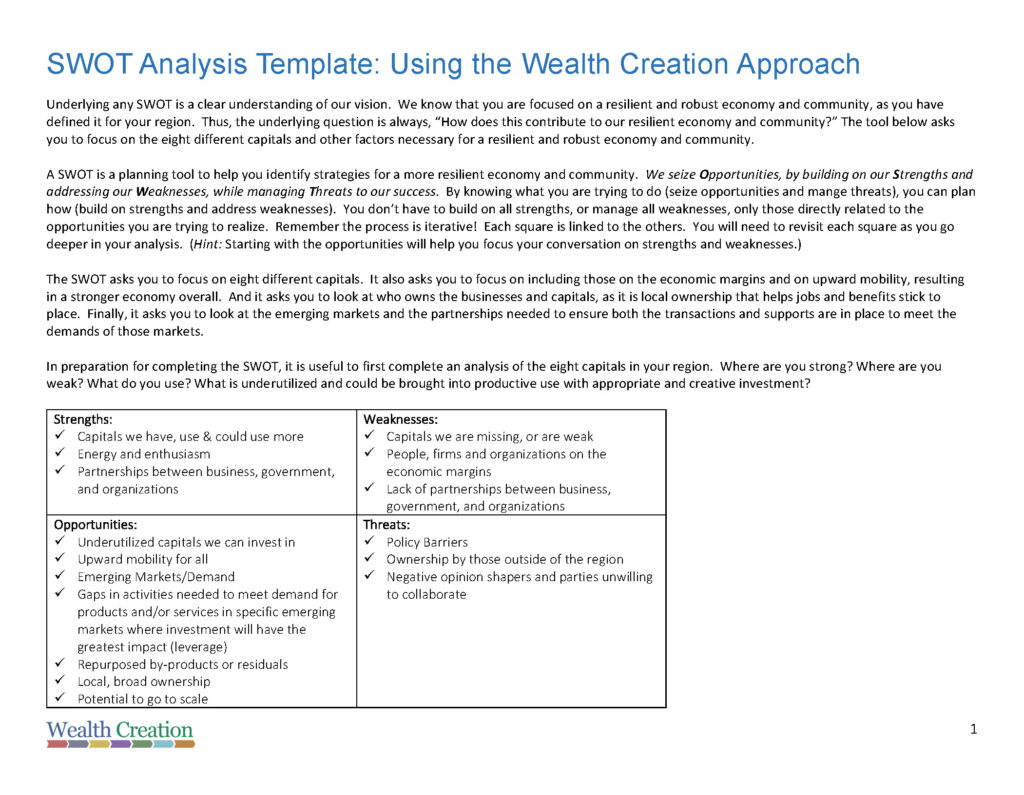

This is an in-depth analysis of regional strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (also known as a SWOT Analysis). Other, similar types of analysis are suggested by EDA, like SOAR (Strengths, Opportunities, Assets, and Risks) or NOISE (Needs, Opportunities, Improvement, Strengths, and Exceptions). For those who do not want to focus on negatives or who want to be more effective in engaging the broadest group of stakeholders, these may be more forward-looking and engaging methodologies to use.

The SWOT or alternative analyses are a useful opportunity to engage stakeholders, whether through a survey, interviews, focus groups, or in-person meetings and better understand the region’s needs.

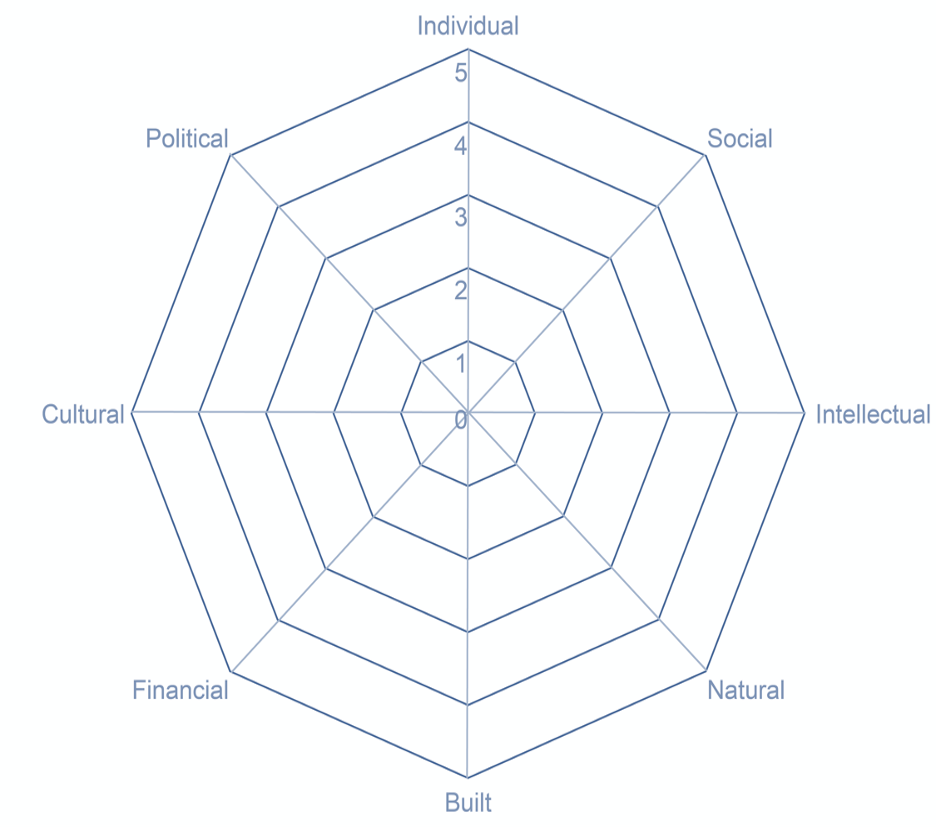

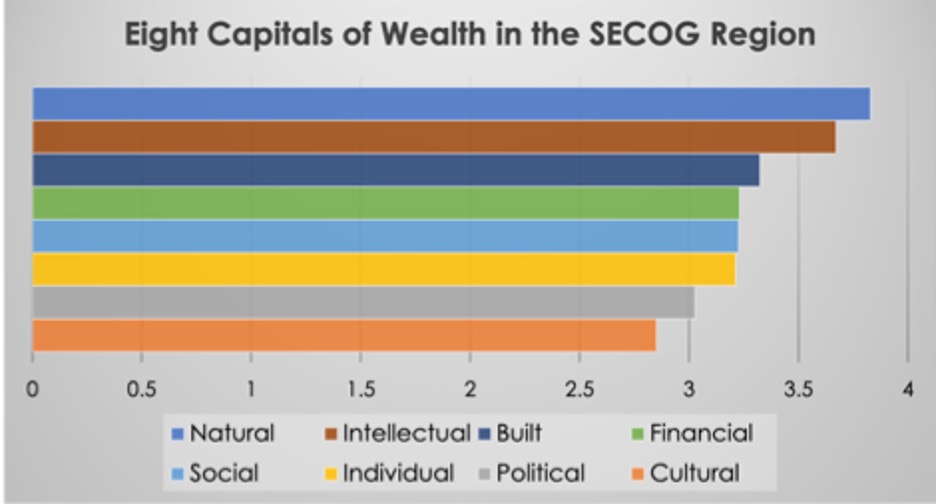

The South Eastern Council of Governments (SECOG) in South Dakota used a survey to undertake its SWOT using the WealthWorks eight capitals. In addition, survey participants were asked to rank each of the eight capitals of wealth using a Spider Diagram.

Find a SWOT Analysis Template on the NADO Wealth Creation microsite.

The Strategic Direction/Action Plan section builds on findings from the SWOT analysis and incorporates/integrates elements from other relevant regional plans (e.g., land use and transportation, workforce development, emergency management, etc.). It also identifies the stakeholders responsible for implementation, timetables, and opportunities for the integrated use of local, state, and federal funds.

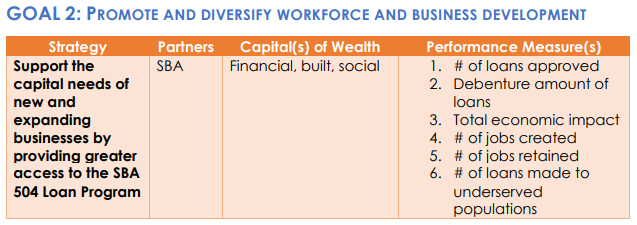

In the SECOG CEDS, there are three key goals in the action plan:

- Facilitate responsible community planning and development

- Promote and diversify workforce and business development

- Foster community vibrancy and resiliency.

Each goal has multiple strategies, each of which notes key partners, capitals affected, and measures.

According to R5DC’s CEDS, “By considering the eight asset banks outlined in this model, goals and strategies cross typical boundaries by asking the question, ‘who else cares about this?’, in turn encouraging collaboration and efficiency in using available resources.” In the Industry and Innovation area and the Social Capital area of the CEDS, R5DC notes a few key strategies:

Industry and Innovation:

- Diversification of business technical assistance at co-working spaces

- Share stories about the opportunity cost LOST if we did not build out all forms of wealth

Social Capital:

- Actively recruit and nurture emerging community leaders through community leadership learning and development opportunities and network groups, with an intentional focus on untapped communities

- Develop intentional “efficiencies and effectiveness” programs and projects with multi -jurisdictional, multi -theme, multi -forms of wealth, multi – sectors/agencies/ departments involvement

- Increase connections across political, socio-economic, race, and age through community listening and collaboration on planning (such as R5DC’s Prioritized Implementation Planning – “PIP”) and projects

- Share stories around cultural and evolving regional identity, including evidence of community pride.

Clearwater Economic Development Association (CEDA) in Idaho identifies in its Entrepreneurship, Business Development and Economic Empowerment Objective a task to “Execute WealthWorks Value Chain mapping to identify and address supply chain gaps and bottlenecks for regional businesses, artisans, and small producers.”

Buckeye Hills Regional Council identifies under the goal of “Work collaboratively with communities to enhance development opportunities surrounding” an objective of “Buckeye Hills staff will complete one (1) regional WealthWorks training for local community officials and one (1) intro to WealthWorks webinar per year for local stakeholders.”

Upper Coastal Plain Council of Governments (UCPCOG) identifies in its Action Plan a key vision that “Community wealth is generated throughout the Upper Coastal Plan Region,” with initiatives including to “improve the region’s ability to foster a diverse, thriving economy;” “Define and promote the region’s sense of place;” and “Build on the region’s competitive advantages and leverage the marketplace.”

Even if wealth creation is not explicitly mentioned in the CEDS, there are elements of it (building wealth, keeping wealth local, building livelihoods) in many CEDS. In the Southern Colorado Economic Development District CEDS, one strategy mentions “Develop and share in the ownership of publicly owned broadband assets.”

The Central South Dakota Enhancement District CEDS references local ownership and control of assets when it lays out the strategy to “Encourage local leaders to invite youth to become involved in organizations, committees, and governing bodies in order to encourage “ownership” of a community.”

The Southern Tier 8 Regional Board in New York references in its CEDS the strategy to “Continue to build a regional local-ownership entrepreneurial community,” also referencing local ownership and control of assets.

The Blackhawk Hills Regional Council in Illinois in its CEDS suggests the opportunity to “Discuss employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) and related models with proprietors.”

The Evaluation Framework is used in the CEDS to evaluate the organization’s implementation of the CEDS and the resulting impact on the regional economy.

Snowy Mountain Development Corporation, an EDD based in Lewistown, Montana, establishes in its Evaluation section: “The organization and communities increase in the eight forms of wealth including: individual, social, intellectual, natural, built, political, financial, and cultural capital.”

For R5DC, “the WealthWorks model plays an important role when evaluating the effectiveness of the [CEDS] goals and strategies, ensuring that eight asset banks, intellectual, individual, social, cultural, natural, build, political and financial, are all considered.”

Wealth Creation Initiatives

EDDs that incorporate wealth creation into their CEDS often include initiatives aimed at fostering local entrepreneurship, job creation, and long-term financial sustainability. While not all EDDs explicitly label their strategies as “wealth creation,” many include elements of it through programs that empower communities and enhance their economic resilience. Here are some notable examples:

Northwest Michigan Council of Governments (Networks Northwest)

- Incorporates strategies to support local entrepreneurship, particularly in agriculture, tourism, and manufacturing.

- Includes programs that build regional value chains, such as linking local farmers to regional markets.

- Promotes workforce development initiatives to ensure local residents can access high-quality jobs.

Southeast Conference

- Supports sustainable resource management, particularly in fisheries and forestry.

- Invests in local ownership of businesses and infrastructure to retain wealth within the region.

- Develops cultural tourism initiatives to preserve and leverage Indigenous heritage for economic growth.

Southern Minnesota Initiative Foundation (SMIF)

- Emphasizes investments in local entrepreneurs and small businesses.

- Provides grants and loans to support community-driven projects.

- Focuses on building generational wealth through access to capital and business development programs.

Mid-Columbia Economic Development District (MCEDD), Oregon and Washington

- Promotes renewable energy projects, including community-owned solar and wind energy initiatives.

- Strengthens local food systems by connecting farmers with regional distributors and consumers.

- Offers business financing programs to support small businesses and startups.

Southwest New Mexico Council of Governments (SWNMCOG)

- Focuses on local capacity building by supporting small businesses and cooperatives.

- Implements renewable energy projects to provide long-term community benefits.

- Encourages value-added agriculture to increase profits for local producers.

East Central Iowa Council of Governments (ECICOG)

- Develops business incubators and accelerators to support local entrepreneurs.

- Encourages investment in affordable housing to create equity for residents.

- Promotes downtown revitalization projects that stimulate local business activity and create wealth.

Takeaways

There are some common themes across Economic Development Districts taking a wealth creation approach. These include:

Encouraging and prioritizing community ownership of resources by local individuals, organizations, and businesses resources.

Building regional markets that enhance local production, connecting it to broader markets, and creating jobs.

Promoting conservation of resources. Focusing on long-term, renewable economic benefits.

Providing loans and grants to support local or regional entrepreneurs and small businesses.

Engaging people and organizations that represent the entire socio-economic spectrum.

Providing education, training, and resources to empower residents. Training residents to fill high-quality jobs in growing industries.

The post Enhancing CEDS with Wealth Creation Strategies appeared first on NADO.

Legal Frameworks – Tribal Engagement 17 Mar 11:32 AM (20 days ago)

Legal Frameworks

Understanding Legal Frameworks for EDD-Tribal Collaboration

Collaboration between Economic Development Districts (EDDs) and Tribal governments requires a strong foundation in the legal and policy frameworks that shape these partnerships. Tribal governments are sovereign nations with unique rights, responsibilities, and relationships with federal, state, and local entities. Understanding these legal principles is essential for building respectful, effective, and sustainable collaborations.

This page provides links to key resources that explain the legal landscape, including Tribal sovereignty, federal trust responsibility, and laws governing economic development in Tribal communities. Whether you’re drafting a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), navigating jurisdictional issues, or seeking funding for joint projects, these resources will help you navigate the legal context of EDD-Tribal partnerships.

Please note: This page is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

1. Tribal sovereignty and federal trust responsibility

These resources explore the legal basis of Tribal sovereignty and federal obligations to Indian Tribes in the United States. Understanding these principles is critical for respecting Tribal self-governance and ensuring compliance with federal trust responsibilities.

- National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) – Tribal Sovereignty

- S. Department of the Interior – Indian Affairs

- Native American Rights Fund (NARF) – Legal Resources

2. Key laws and policies

These federal laws govern the specifics of US Government-Tribal Nation relationships. They address areas such as self-governance, cultural protection, economic development, and public safety.

- Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA)

- Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)

- Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA)

- Tribal Law and Order Act (TLOA)

- Buy Indian Act

3. Economic Development-Specific Laws and Programs

These federal programs support economic development in Tribal communities. They provide funding, technical assistance, and opportunities for infrastructure, energy, and small business development.

- Indian Community Development Block Grant (ICDBG)

- Tribal Energy Resource Agreements (TERA)

- Small Business Administration (SBA) – 8(a) Business Development Program

4. Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) Guidance

These links provide resources for drafting MOUs or other partnership agreements between EDDs and Tribal governments. MOUs are essential tools for formalizing collaboration and clarifying roles and responsibilities.

5. Jurisdictional and Land Use Considerations

These links include resources on jurisdictional issues and land use planning, which are often critical in EDD-Tribal collaborations. Understanding these complexities is key to avoiding conflicts and ensuring successful projects.

- Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) – Land and Water

- Tribal Court Clearinghouse – Jurisdiction

- National Indian Law Library (NILL)

6. Additional Legal Resources

Links to organizations and databases that provide comprehensive legal information for Tribal governments. These resources can help EDDs and Tribes navigate complex legal issues and build stronger partnerships.

The post Legal Frameworks – Tribal Engagement appeared first on NADO.

Engagement Resources – Tribal Engagement 17 Mar 11:26 AM (20 days ago)

Tribal Engagement Resources

Engagement Resources for EDD-Tribal Collaboration

Collaboration between Economic Development Districts (EDDs) and Tribal governments involves navigating complex cultural, legal, and logistical considerations. Effective engagement requires an understanding of Tribal sovereignty, cultural values, and the frameworks that guide partnerships. This page provides resources to support EDDs and Tribal governments in building respectful and productive working relationships.

The resources included here cover topics such as cultural competency, Tribal consultation, training opportunities, and tools for community engagement. They are intended to help users better understand the context and best practices for working with Tribal governments. Whether you are drafting agreements, planning projects, or seeking to improve communication, these resources offer guidance and information to support your efforts.

1. Cultural Competency and Awareness

These resources provide foundational knowledge about Tribal history, culture, and governance structures. They may be beneficial for training on fostering respectful and informed engagement with Tribal governments.

- National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) – Tribal Nations & the United States

- Native Knowledge 360° – Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

- S. Department of the Interior – Tribal Leaders Directory

2. Tribal Consultation and Engagement Best Practices

These resources offer guidance on conducting meaningful Tribal consultation and engagement. They include frameworks and best practices for ensuring Tribal voices are heard and respected in collaborative efforts.

- Environmental Protection Agency Tribal Consultation Guide

- Department of the Interior-Tribal Consultation Manual

- Department of Transportation-Tribal Consultation Plan

3. Training and Workshops

These links connect users to organizations and programs offering training on Tribal engagement and cultural competency. They provide opportunities to build skills and knowledge for effective collaboration.

- Native American Rights Fund (NARF) – Training Resources

- National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA) – Training and Events

- Tribal Governance Training – Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development

4. Tribal Organizations and Networks

These resources provide directories and networks to help EDDs connect with Tribal governments and organizations. They serve as valuable starting points for building relationships and partnerships.

- National Congress of American Indians (NCAI)

- United South and Eastern Tribes (USET)

- Inter-Tribal Council of Arizona (ITCA)

- Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board

5. Community Engagement Tools

These resources offer practical tools and frameworks for engaging communities in collaborative projects. They include guides and templates for planning and implementing engagement strategies.

- Community Tool Box – University of Kansas

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) – Resources

6. Data and Mapping Tools

These tools may help EDDs and Tribal governments identify shared priorities and opportunities for collaboration. They include data sets, maps, and other resources for planning and decision-making.

The post Engagement Resources – Tribal Engagement appeared first on NADO.

EDD Tribe Map – Tribal Engagement 17 Mar 11:16 AM (20 days ago)

EDD-Tribe Map

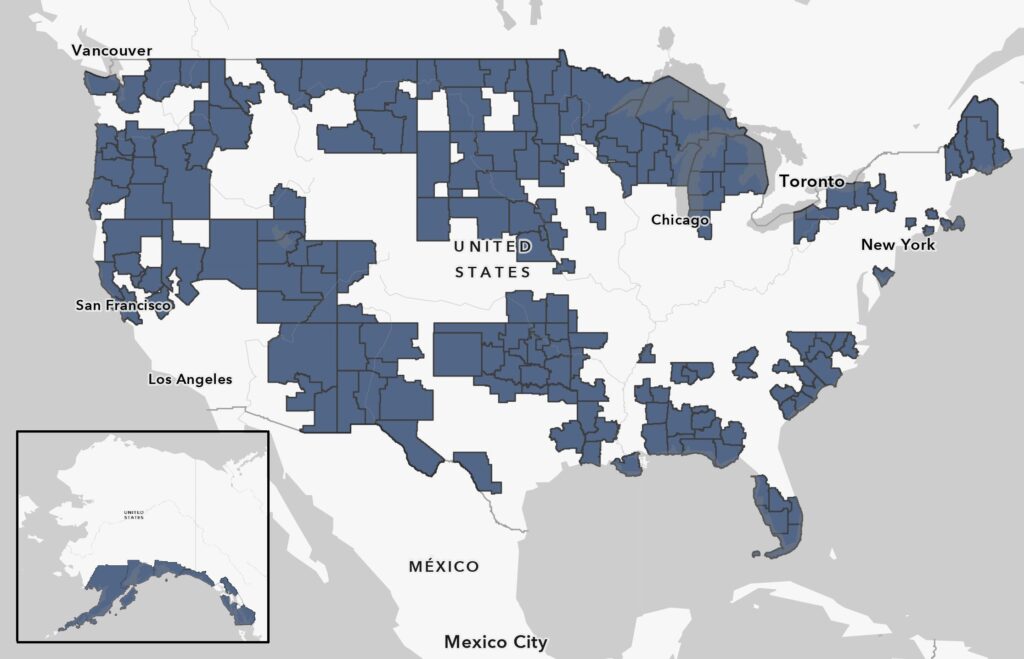

The following map illustrates the overlaps between EDD service areas and Tribal Reservations and Off-Reservation Trust Lands. Click on a Tribal Reservation or EDD to access the corresponding CEDS, if available. Contact Dion Thompson-Davoli at dthompson-davoli@nado.org with questions or to request changes.

The post EDD Tribe Map – Tribal Engagement appeared first on NADO.

Webinar – Tribal Engagement 17 Mar 11:13 AM (20 days ago)

Tribal Engagement Webinar

This webinar, recorded August 19, 2024, reviews successful strategies for EDD-Tribe engagement. Speakers include:

- Carolee Wenderoth, Tribal Engagement Coordinator at EDA

- Dr. Joanie Buckley, Consultant, First Nations Development Institute

- Frank Metlow, Deputy Executive Director, Tri County Economic Development District

- Jeff Hagan, CEO, Upper Peninsula Regional Planning

- Kristin Smith, Executive Director, Prince William Sound Economic Development District

The post Webinar – Tribal Engagement appeared first on NADO.

Engagement Strategies – Tribal Engagement 17 Mar 10:49 AM (20 days ago)

Tribal Engagement Strategies

Introduction

Economic Development Districts (EDDs) and American Indian and Alaska Native Tribal Nations frequently represent overlapping or adjacent geographies, which often leads to a shared interest in regional economic development topics. However, the extent of relationships between EDDs and Tribal Nations varies widely across the United States. Some have deep and enduring partnerships, including official Tribal representation as EDD members or on the organization’s board of directors. In other places, Tribal Nations and EDDs have a limited history of collaboration or official contact. Many EDD staff report that they wish to expand their relationships with local tribal nations. However, they are often unsure how to respectfully involve these partners in established planning and implementation processes. This brief outlines opportunities for EDD-Tribal collaboration, as well as tips for EDD staff seeking to initiate relationships with Tribal Nations. It highlights the value of looking at economic development holistically and inclusively.

Background: Tribal Reservations in the United States

The legal framework that governs relations between the U.S. Federal Government, U.S. states, and American Indian or Alaska Native Tribes is complex, encompassing varying legal duties, moral obligations, and informal understandings and expectations shaped over the course of the 250-year history of the United States. The U.S. Government presently recognizes 574 American Indian and Alaska Native tribes and villages, and 326 Indian Reservations. Not all federally recognized Tribes have an associated Reservation, though some Reservations are held in trust by more than one Tribe. U.S. states recognize approximately sixty-five additional Tribes. State recognized Tribal Reservations differ from federally recognized reservations in that they are typically subject to all state laws but exempt from state property taxes. 1

As recognized sovereign nations, Tribes govern with all powers of self-government except those relinquished under treaty, by Congressional statute, or by federal court ruling. Tribes may form independent governments, establish taxes, make and enforce laws, license and regulate economic and other activities, determine standards for tribal citizenship, and exclude unwanted persons from their lands. They may also enter into government-to-government agreements with the U.S. Federal Government, states, localities, and other public entities Not all tribally owned land is held on Tribal Reservations. Fee lands, for example, are property owned by tribal members that can be freely bought and sold like any other parcel in the United States. The conversion of fee lands to trust lands, or the inverse, has been the subject of significant and complex actions over the last 150 years and has major implications for tribal economic development. This Congressional Research Service report analyzes this issue in some depth. It is critical for EDDs who wish to partner with Tribal entities to understand the legal rights, duties, and responsibilities entailed by Tribal Nation sovereignty, as well as the centrality of Tribal sovereignty to questions of identity and belonging in Indian country and the United States. Though it is not necessary to become an expert, a strong working understanding and respect for the complexity and gravity of this framework can help EDD staff begin to establish trust with potential partners.

Background: EDD-Tribe Relationships

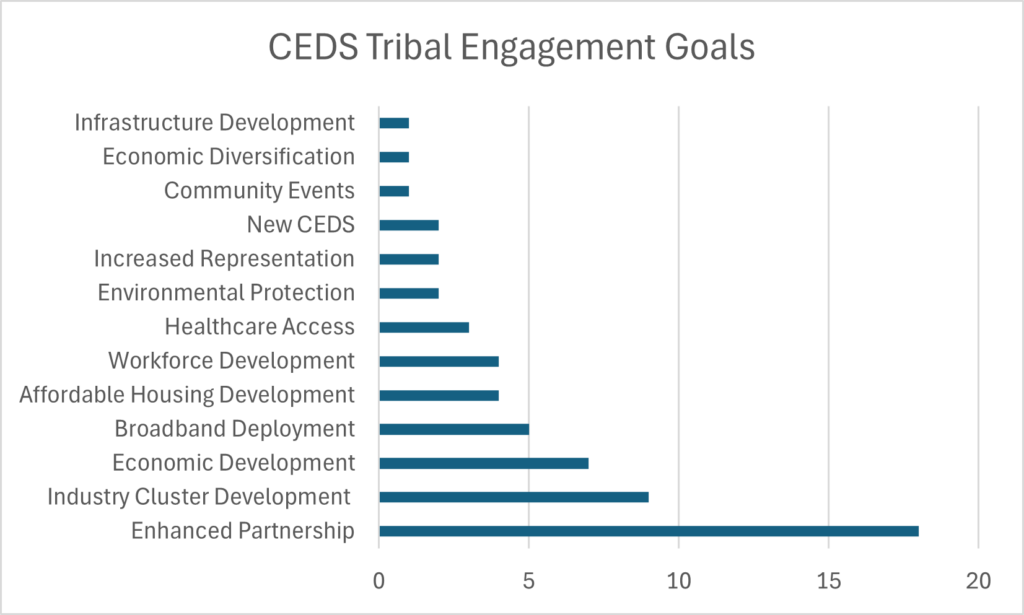

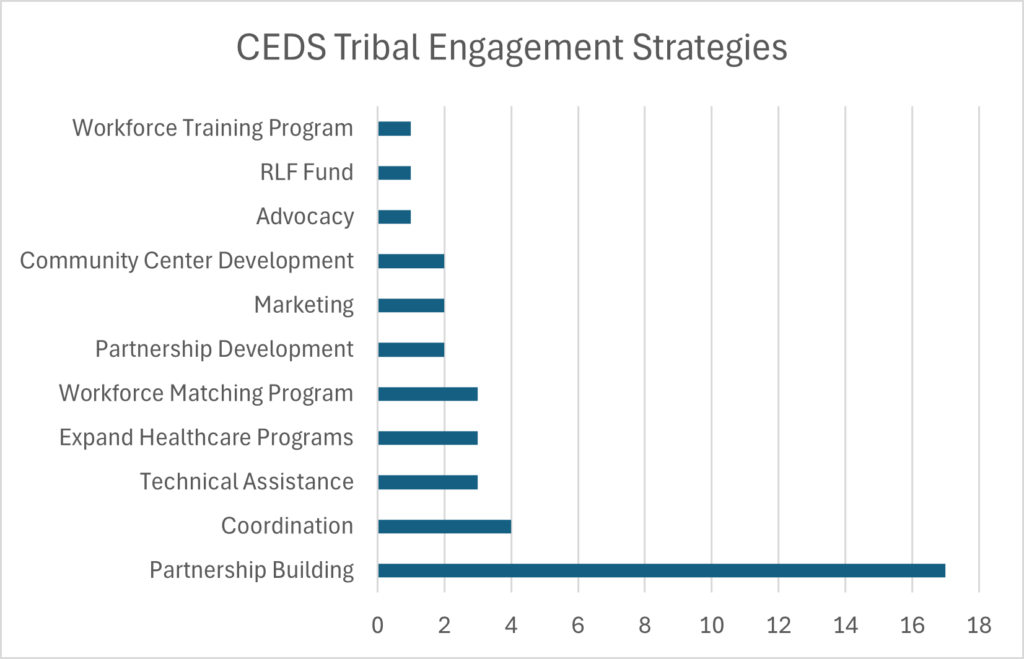

The U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA)’s Planning Program requires that all partnership planning grantees, EDD or tribal, write and maintain an individual Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS). This includes EDDs and Tribes with overlapping boundaries. Each of the approximately 400 EDDs and number of Native American/Alaska Native Planning Grantees maintains an individual CEDS outlining their five-year program of economic development goals and activities. More than 150 EDDs have service areas that overlap with Tribal Reservation, Off-Reservation Trust Lands, or Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Areas, and dozens more share at least one border. In some cases the overlap is substantial; for example, more than half of the Northern Arizona Council of Governments’ service area overlaps with Navajo Nation boundaries. Still, the two each complete their own CEDS. Dozens of EDDs have existing relationships with tribal entities in and around their service areas to promote and enhance regional economic development. The extent of these relationships ranges from informal contact at the staff level to tribal representation as EDD members or on an EDD board of directors. For example, the Southeast Conference based in Juneau, Alaska includes several tribes and Alaska Native associations among its membership, and the Principal Chief of Osage Nation sits on the Board of Directors of the Indian Nations Council of Government, an EDD serving the Tulsa, Oklahoma region. A recent Economic Development District Community of Practice (EDD CoP) survey of EDD Executive Directors and review of 402 recent CEDS plans across the country found that at least 70 EDDs have existing relationships or are seeking to build relationships with local Tribal communities. Tribal members often sit on EDD CEDS committees, or partner on specific projects like broadband deployment, RLFs, hazard mitigation planning, and food ecosystems development. A number of EDDs have offered technical assistance to Tribal Nations for their CEDS process or other planning efforts. The two charts below display a snapshot of goals and strategies for tribal engagement voiced in CEDS plans.

There is also frequent government-to-government consultation between EDDs and Tribal Nations for projects that invoke National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) or National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Section 106 reviews. Section 106 requires that agencies identify historic properties, assess effects to historic properties, consider alternatives to avoid, minimize, or mitigate any adverse effects, and document their resolution, including through a stakeholder engagement process with Indian Tribes, among others.

Planning Context

As noted above, many EDD service areas overlap with Tribal Reservations. Beyond overlapping administrative boundaries, tribes play a critical role in the formation of regional cultures and economies. Transportation infrastructure, freight flows, people, wildlife, and services cross freely over these lines, collectively creating regional economic activity and physical, cultural, and ecological dependencies. Because of these interdependencies, siloed efforts amongst EDDs and Tribal Nations cannot result in truly comprehensive regional plans and can lead to missed opportunities, overlapping programs, and unrealistic analyses of regional needs. At worst, they could result in the pursuit of projects or strategies that are at cross-purposes. The situation also precludes the possibility of fulsome and equitable public engagement for projects and programs of regional significance. In contrast, regional cooperation between tribes and EDDs can create force multiplier effects, where the resources and opportunities of adjacent areas feed into and build on each other. BUILDING COMMUNITY The interests that Tribal Nations represent are not merely economic in nature but include nurturing the social and cultural flourishing and continuation of their communities, histories, and traditions. As such, outreach to these communities should consider holistic approaches and highlight shared goals beyond simple economic impacts. At their core, EDDs are convening organizations that bring people and communities together to solve complex regional challenges. Creating communities of trust and mutual understanding is critical to that mission, both for specific projects and for the long-term resilience of regions and places. While all the tips and tools in the following section are important, it is critical that community is at the center of this work.

With this context in mind, the following is a list of engagement tips for EDDs looking to start (or renew) a relationship with Tribal Nations in or adjacent to its service area. These tips were sourced from staff at EDDs with strong Tribal relationships as well as from experts on Tribal engagement in the EDD Community of Practice team and from federal partners.

Tips for Outreach

1. Make Cultural Awareness a Top Priority

Respect for tribal sovereignty must be a guiding principle for any EDD-tribe relationship. Unlike localities, counties, or other governmental bodies, Tribal Nations have the right to total self-determination and governance within their Reservation boundaries. EDDs seeking to partner with tribes must understand that the tribal entity enters that partnership voluntarily and retains full autonomy over governance decisions within its borders. It is also crucial to be mindful of the significance of the historical context of government relations with Indian tribes and to familiarize yourself with the particular history of that relationship with the tribe you seek to partner with. Understanding that history, as well as the tribe’s particular customs and rituals, can help to bridge cultural divides and potential skepticism or mistrust.

2. Understand the Particular Laws and Customs Governing Your EDD and its Tribal Partners

It is important not to oversell or mislead emerging partners about the potential for collaboration allowed under the law and enabling statutes for regional organizations. For example, the state enabling statutes governing some EDD host organizations require that their board be comprised solely of representatives from counties or localities. Other EDDs face no such restrictions. This applies to tribal governance procedures as well: it is important to recognize that each tribe has a unique governance structure and degree of public sector capacity. A clear understanding of the legal and organizational structure and requirements of a particular EDD and the Tribe it seeks to engage is critical to ensure a transparent relationship.

3. Be Sensitive to Time and Costs

Tribal representatives frequently juggle many duties beyond the particulars of an outside engagement process and may face constraints on their human and financial capacity. This can create barriers to collaboration on projects that require significant investments of time or staff capacity. Clearly expressing the timelines and demands of a collaboration at the front end is critical, as is avoiding setting up unnecessary deadlines or requests. Things as simple as regular meetings may be burdensome for tribal partners who may have to travel long distances to attend.

It is also important to recognize that tribal governance processes may create a slower timeline for decision-making than is typical with EDD partners. Tribal officials may need to consult with others, including elders, the tribal council, or the head of the tribal government between engagements or steps in project processes. Understanding the timelines for tribal decision making processes at the start can help EDDs avoid setting unrealistic expectations or inviting unnecessary conflict.

4. Start Small

Many EDDs report that successful tribal relationships began with a single, small collaboration and then grew at the speed of trust. For example, the Section 106 consultation process can be a jumping off point for relationship building between tribes and EDDs that have participated in it in the past. Once these small engagements begin to establish trust, EDDs can more easily approach Tribal Nations to offer technical assistance, collaborate on grants, or co-establish services. Successful completion of small projects can lay the foundation for a tribal entity to see the EDD as a trusted partner with a particular expertise and many shared interests.

5. Commit for the Long Term

To foster an enduring partnership with a Tribal Nation that shares a mutual interest in regional economic development, it is critical to institutionalize the partnership as soon as is appropriate. The most common approach taken by EDDs is to invite Tribal leaders to sit on committees, including the CEDS committee, workforce development board, or others that represent shared interests. Some EDDs have established Tribal Advisory Committees that regularly weigh in on the impact the organization is having on tribal lands and peoples. Institutionalized partnerships are important for maintaining relationships beyond the span of any single EDD staff member’s career or Tribal Member’s time in office.

The post Engagement Strategies – Tribal Engagement appeared first on NADO.

EDD – Tribal Engagement 17 Mar 7:43 AM (20 days ago)

EDD – Tribal Engagement

American Indian Tribes hold a unique and sovereign place in the fabric of the United States, with rich histories, cultures, and traditions that have endured for centuries, shaping the nation’s identity, stewarding its lands, and governing the political and social lives of more than one million of its citizens.

Collectively, the 574 federally-recognized American Indian tribes and Alaska Native entities exercise sovereignty over 326 separate reservations with more than 50,000,000 acres of land in 26 states. Tribal governments and reservations are considered sovereign and have the authority to govern themselves, make and enforce laws, manage their lands and resources, and determine their own cultural, social, and economic futures.

For Economic Development Districts (EDDs) whose service areas overlap with or border Tribal lands, Native American Tribes are an important constituency and potential partner across a variety of domains. In many regions, Tribal enterprises (businesses owned and operated by Native American tribes) are critical economic engines, and Tribal members contribute to community life in the workforce, in schools, and in social settings. Moreover, Tribal cultural institutions and memory are often defining characteristics of a region’s character.

Despite this, EDDs sometimes struggle to build or maintain relationships with Tribal governments. There are a variety of challenges–cultural and operational divides, communication challenges, organizational capacity, a lack of institutionalized connections, and more.

This microsite provides a variety of resources for EDDs looking to build or expand their working relationships with Tribal governments and Tribal enterprises, including tips from EDDs who have been there before, case studies, webinar recordings, and more. These resources are designed to support stronger partnerships, deepen understanding, and foster meaningful collaboration between EDDs and Tribal governments to promote shared prosperity and resilience.

The following map illustrates the overlaps between EDDs and Tribal Reservations and trust lands across the United States. Click on your district or on a Tribal area to see its CEDS, if available, and other useful information.

This resource is offered through the Economic Development District Community of Practice (EDD CoP), managed by the NADO Research Foundation to build the capacity of the national network of EDDs. To learn more, visit: www.nado.org/EDDCoP. The EDD CoP is made possible through an award from the U.S. Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce (ED22HDQ3070106). The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations in this resource are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

This research was presented by NADO Research Foundation Program Manager Dion Thompson-Davoli. You can reach Dion at dthompson-davoli@nado.org.

The post EDD – Tribal Engagement appeared first on NADO.

EDA Reauthorization Legislation Signed into Law 4 Feb 12:19 PM (2 months ago)

EDA Reauthorization Legislation Signed into Law

For the first time in 20 years, Congress has reauthorized the US Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration (EDA). On January 4 2025, the Thomas R. Carper Water Resources Development Act of 2024 (S. 4367) was signed into law, following its passage in the House and Senate with overwhelming bipartisan support. The reauthorization of the EDA will strengthen and protect EDA’s programs and will enhance key initiatives that are vital to the success of NADO members and Economic Development Districts across the country. The legislation also bolsters many of the core traditional programs that EDA has administered ever since it was originally authorized in the Public Works and Economic Development Act of 1965. NADO extends our gratitude to the countless champions who helped make this legislative victory possible, including NADO’s membership and leadership, the member organizations of the EDA Stakeholders Coalition, and the Congressional members and staff who helped champion this legislation.

The post EDA Reauthorization Legislation Signed into Law appeared first on NADO.

Webinar: WC Lessons from the Butterfield Stage Experience 30 Jan 11:50 AM (2 months ago)

Webinar: Building Resilient Value Chains: Lessons from the Butterfield Stage Experience

When: Tuesday, January 28, 2:00 p.m. ET

This webinar shared the story of the Butterfield Stage Experience, a gravel bike route in Missouri, as well as the various partners critical to building this value chain. The webinar also provided space for participants to network and engage in a discussion of ways to integrate value chain thinking into their own work.

The post Webinar: WC Lessons from the Butterfield Stage Experience appeared first on NADO.