Drascombe & Devon Lugger vs the Dabber

Designed for safe family boating under sail, or or power, but taken long distance by intrepid sailors, Clive Marsh looks…

Prolific small boat owner Clive Marsh shares his experience of sailing Drascombe and Devon Luggers

While renting a cottage at Flushing, west Cornwall, I got to sail Luggers for the first time.

The hired boat was kept on a swinging mooring in view of the lounge window and could be accessed at any state of the tide using the tender that came with the accommodation.

We were taking one of those short autumn breaks which are cold and rainy every day. But this didn’t put us off enjoying the Lugger.

At the time, I owned a fin-keeled Westerly yacht, and I was looking forward to the traditional simplicity that Luggers are famous for, like pulling up at the beach at St Mawes and going to the pub.

Negotiating the moored yachts at Falmouth under jib and mizzen. Credit: Clive Marsh

I also liked the idea of being able to row the boat when there was little wind and the engine was playing up.

As I clambered aboard from the tippy tender, it was noticeable how stable the Lugger was even before I lowered her heavy galvanised steel centreplate.

There was plenty of room in the cockpit for my family of four, much more space than there was in the cockpit of our Westerly yacht, in fact.

But what was particularly nice was being able to walk forward and let go from the mooring buoy in more safety than it would be on the deck of a small yacht.

It was all very convenient and simple and perfect for messing about in Falmouth Harbour.

It was blowing a good Force 4-5, so I sailed off the mooring under just jib and mizzen.

This is a very handy and easily managed arrangement. I had the motor on tickover in neutral just in case while I manoeuvred through the moored yachts.

I didn’t put the main up that day and was happy just to potter around Falmouth Harbour in the rain and enjoy the few moments when the sun shone through.

During the course of our break, we tried every option the Lugger gave: rowing, motoring, motor-sailing, full rig, main only, jib and mizzen etc.

I decided there and then that I must have one of these versatile boats and within a few weeks became the owner of Lugworm, a Mk1 Lugger with a rope horse, named after the famous Drascombe Lugger sailed by Ken Duxbury on his many open sea passages.

I gave Lugworm a new name, Spray, as I like short names for my boats.

Drascombe Lugger at Salcombe; Luggers are ideal family boats. Credit: James Bell (PS)/Alamy

She was an early glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) boat on an old T-type trailer. The first thing I did was invest in a new swing-back trailer supplied by Drascombe.

This meant the total cost of the oldish boat and the new trailer came to £6,500, which was more than my old Westerly was worth.

Good dinghies and day boats may cost more than old small cruisers, but they save a lot in marina and haul-out charges.

Early Luggers have a simple steel tube as a horse for the mainsheet.

My old Lugger unusually had a rope horse which worked perfectly well. Later models have a mainsheet track.

The jib had roller furling and the mizzen was sheeted out to a long bumpkin which was great at sea but vulnerable in the rivers at close quarters when coming alongside etc.

Some owners have fitted a boom to their mizzen and done away with the bumkin, but I like bumkins which are simple and go with the style of a Lugger.

The mainsail had no boom, and I tried different sheeting positions. The only modification I made was to remove the roller furling jib for a simple hank-on jib because it is easy to just walk forward and handle the jib in an open boat.

The less string, the better for me. That’s a personal preference of mine, but most people like their roller furling jibs.

I initially kept Spray on her nice new trailer and towed her to a variety of places on the South Coast.

Country bed and breakfasts a few miles from the coast are more likely to have space for you to keep the trailer.

Towing this new trailer that fitted the boat perfectly was a doddle. I did not need to immerse the ‘sealed for life’ type bearings, but the inevitable dunking did happen a few times on crowded slipways, and I discovered that I could not change the bearings on site like I could with my old tapered variety.

These sealed-for-life bearings needed a bench press in a garage. I had them checked at a garage, and, yes, one set had corroded.

Later, for another boat, I specified tapered bearings for a newly-built trailer. Again, this is a personal preference; some people prefer the sealed-for-life variety, but I like to be able to inspect and change my bearings at home on the drive.

After a while, I decided to antifoul Spray and keep her on a mooring at Rye. This worked very well; the Lugger has a well-fitting cockpit cover, which enables the rain to run onto the side benches and out through their scupper holes.

The cockpit was always dry. Sailing on the open sea under just jib and mizzen was a very pleasant experience, and Spray held her course without much help from me.

Under full sail, she romped along and was easy to sail single-handed.

Clive’s old Mk1 Lugger at Rye. Credit: Clive Marsh

The rudder arrangement takes a bit of getting used to. The heavy steel plate drops through a slot on deck. The weight of this plate adds to stability, but it is awkward to raise.

This made beaching the boat difficult, but I see that modern Luggers have alternative arrangements.

The oak tiller was attached to the rudder stock with a bolt, and this was a weak point. Mine broke off just as I entered the narrow River Rother from the sea, which made things a bit awkward.

My local blacksmith made me a steel tiller, which solved that little problem. Latter models have better arrangements.

The outboard motor fits into a very convenient well, and I always found a 4hp more than adequate, although the recommended power is 5-6hp.

There is a big difference in weight between a 4hp and a 5hp, which is why I prefer the lighter 4hp.

Rowing was surprisingly easy once the boat was moving. I once launched from a slip on the Percuil River, which is just up from St Mawes.

I noticed a bungalow for rent, which came with a later model Drascombe Lugger, and for several summer breaks, I rented it. This saved me 450 miles of towing, and it was nice trying out a newer Lugger with her many little improvements.

The original Drascombe Luggers were built by Honnor Marine, but when this company ceased trading in the late 1990s, the moulds and the Drascombe name went their separate ways – the licence to use the Drascombe name to McNulty Boats in late 1997 and the original moulds to a new Honnor Marine company.

McNulty created new moulds taken from a set of original boats. When McNulty closed down in August 2002, it was taken over by Churchouse Boats (now called Drascombe Boats), which continues building to this day.

Honnor Marine is also still building Devon Luggers using the original Drascombe moulds.

So the two boats are much the same, and both current builders give useful advice and can help sailors to buy and sell their Lugger and provide spare parts.

To avoid confusion, I refer to the boats simply as Luggers – though to be pedantic, neither of these boats has a lug sail.

These Luggers must be one of the best and most versatile boats designed, which is why more than 2,000 have been built.

The Drascombe Association (www.drascombe-association.org.uk) produces a useful journal, has a forum, and provides advice, UK-based events and meetings arranged throughout the year.

Designed for safe family boating under sail, or or power, but taken long distance by intrepid sailors, Clive Marsh looks…

Visit any UK harbour in the summer and the chances are you’ll see a Drascombe Lugger or a Devon Lugger…

For such a venerable name in the world of boating as Drascombe, the launch of a new model is quite…

Ben Lowings shares his tips for dingy cruising around the UK and further afield

Want to read more boat articles?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter

From bareboat to skippered or flotilla holidays, Laura Hodgetts looks at options for sunnier climes a few hours’ flight away

Just a short-haul flight away from the UK, warm sunshine and a sailor’s playground awaits.

The Mediterranean coast stretches approximately 2,500 miles and encompasses 23 countries, boasting varied landscapes, cultural gems and countless islands, islets and bays.

Cruising hotspots range from traditional Greek fishing harbours to Italian escapes that rival Caribbean settings, Croatian National Parks to sleepy Turkish bays.

While it’s hard to choose a favourite cruising area, the team at Nautilus Yachting, which has been organising sailing holidays in the Mediterranean for over 30 years, said: “Few sailing areas offer more possibilities than Croatia’s Dalmatian Coast. Split and Dubrovnik are among the most popular tourist hotspots, although charterers can find pure escapism by anchoring free of charge by uninhabited islands in the Kornati or experience vibrant nightlife at Hvar.”

Yacht charter in Europe: Pula is recommended as a ‘slightly quieter spot’ along the popular coast of Croatia. Credit: Leonid Tit/ www.helm.yt

A one-way charter between Split and Dubrovnik is a popular option for sailors wishing to ‘pack in as much as possible’.

Sunsail, which has bases in Agana and Dubrovnik, has expanded its Croatian offering with an adventurous ‘Libertas flotilla’, with a focus on rugged coastlines exploring coves, picturesque harbours, swimming, scuba diving and snorkelling. Prices for seven nights start from £3,360 for four passengers on a 34ft yacht.

Adi Tognarelli, a founder at PlainSailing.com, agrees that Croatia is a hotspot for 2025 bookings, although this was not the case last year.

Adi said: “We’re seeing a trend back towards Croatian waters – last year there was a drop off as prices have gone up and up in the last five years, and for the first time in many years there was last-minute boat availability in Dubrovnik even in high season (usually every single boat is sold out many weeks in advance).

Check with the charter company to see if lifejackets are provided for your yacht charter in Europe. Credit: Steppenwolf/Alamy

“The marinas have also gone up quite a bit since Croatia joined the Eurozone, which made it much more expensive than its old rival Greece, where staying moored up overnight can typically be around 75% cheaper. We’ve also seen a growing number of new enquiries asking to take the boat from Montenegro down to Albania, which is a new and growing sail tourism area. Not all that many companies have the insurance needed to cover the territories, but some do, and Albania has the same stunning coastline and beautiful old towns to explore, often at great prices.

“With Albania being the last piece in the puzzle, it hopefully means that in a few years time you’ll finally be able to charter a boat from Croatia and sail it one way down to Greece, linking the cruising grounds for the first time.

“Italy, Mallorca and the South of France remain as popular as ever.”

The team at HELM has noticed that while Croatia and Greece “remain hugely popular”, they are seeing a resurgence of charters in Turkey and “slightly quieter spots, like Pula in North Croatia”.

James Foot at HELM recommends their new base in Kaş, Turkey, “in a beautiful natural bay away from the hustle and bustle of Fethiye and giving direct access to remote areas like the bay of Kekova Roads.”

Drone footage of the peninsula and Setur Marina in Kaş district of Antalya. Credit: www.helm.yt

He added: “We always suggest avoiding August if at all possible. The best times to sail in the Mediterranean are usually June and September, outside of the peak busy periods but benefitting from lovely warm weather, without oppressive heat.”

Chartering from smaller marinas where there is only one charter fleet in operation can help to ‘keep things peaceful.’

Foot said: “Starting in Sivota, Greece, rather than Lefkada, for example, keeps you away from the Saturday chaos and gains you the advantage of being a day ahead of the south Ionian flotillas – all for the price of an extra 40 minutes down the coast road. The further east you go, the longer the season lasts – I took my family to the Dodecanese in early October 2024, and we had 24°C all week. If you have a particular yacht or specific requirements in mind, we recommend booking early to lock in your chosen boat and take advantage of early booking discounts.”

New for 2025, Seafarer cruising and sailing holidays is offering one-way ‘explorer flotilla’ routes this summer, with the start alternately in Kiato and Korfos.

One week will see the flotilla start in Korfos and, after crossing the Corinth Canal, explore the Gulf of Corinth, “an area off the radar for most sailors”.

The second week begins in Kiato in the Gulf of Corinth, cruising through the iconic canal before exploring the Saronic Gulf.

Running from April to November with 35-45ft monohull options, sailors can expect an average daily distance of 18 miles. Prices are £1,823 for a Bavaria 37. A skipper can be provided for £1,295 per week.

Chris Lorenzo, Seafarer managing director, said: “Reliable sunshine on the Corinth and Saronic Gulf flotilla is all but guaranteed during the season between May and October, with temperatures ranging from the low 20s in early and late season up to the mid to high 30s in late June through August. Sailing conditions are generally moderate with winds typically Force 3-5.”

Surprisingly predictable and gentle winds in the summer months are a draw of the Greek Ionian. Credit: www.sunsail.com/uk

Sunsail has noticed a 7% year-on-year increase in European charter bookings from the UK market, with Lefkas in Greece the top spot, plus a ‘slight increase’ in flotilla bookings.

Katrina Lawson, head of brand and acquisition at Sunsail, said: “Lefkas is one of our most accessible sailing destinations, with affordable mooring options, making it a more budget-friendly holiday which may be why it’s so popular. The Ionian Sea around Lefkas is renowned for its predictable and gentle winds, particularly in summer. The mix of calm morning breezes and moderate afternoon winds makes it an excellent choice for sailors of all skill levels.”

Sunsail’s Lefkas base offers flotilla, bareboat, skippered and sailing schools.

In peak season, some flotillas include a children’s co-ordinator, as well as a host, skipper and technician.

Other trends include an 8% increase in Sunsail’s Croatian bookings year on year, driven by Dubrovnik, which is up 35%. Agana is up 9% on bareboat bookings; 38ft and 41ft vessels are the most popular.

One of Nautilus Yachting’s top 10 destinations is Sardinia, the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, where its Emerald Coast beaches ‘rival the Caribbean’.

The Maddalena National Park is a haven of over 60 islands, home to bottlenose dolphins and turtles. Highlights include Budelli’s pink beach, Caprera, Razzoli, Santa Maria, Santo Stefano and Spargi.

Island of Budelli, Sardinia famed for pink sand. Credit: Paolo Reda – REDA &CO/Alamy

Nautilus Yachting’s business development manager, Leanne Kiffor,d recommends experiencing two countries in one trip by sailing from Sardinia to Bonifacio on the French island of Corsica, which is “within easy reach and has the dramatic entrance through the narrow opening in the cliff; the Bocche di Bonifacio is not to be missed.”

En route, visit the Lavezzi Islands nature reserve, dubbed the ‘Seychelles of the Mediterranean’ due to its large rocks.

Confident sailors with the right licences – RYA Day Skipper or International Certificate of Competence (ICC) – can save a fortune by opting for a bareboat charter – skippering the boat either in company (with a flotilla) or by following the charter company’s recommended routes.

James Foot at HELM has noticed an increase in people selecting skippered charters as a choice rather than a necessity: “It may be older sailors who have lost a little confidence at sea, or sailors who want to relax and not worry about the damage deposit.”

Whether you join a flotilla with friends or family, or not, the frequent get-togethers and

shared experiences will create a familiar group by the end of your yacht charter in Europe. Credit: Nautilus Yachting

Eloise Barker, an experienced sailor and travel writer at Responsible Travel, recommends: “When it comes to sailing in more popular destinations like the Greek Islands, a little local knowledge goes a long way to making your trip better.”

She added: “You’re much more likely to get a chance to check out small off-the-beaten-track ports, drop anchor in hidden-away coves or discover the restaurants local people love. These kinds of charters help you minimise your impact on over-touristy destinations too. You can spend less time in busy areas, and you’ll be helping to make sure your money reaches local people’s hands. You can also choose a boat that provisions from local suppliers, not just big supermarket chains.”

Bigger groups can split the cost of a skipper. For example, in mid-July, a Sunsail 404 Classic four-cabin catamaran on its Croatian Libertas flotilla costs £9,798 for six people with a skipper, which works out at £3,266 per couple. Remember that a skipper will require a berth.

The €200 a day may seem a luxury, but if their local knowledge removes the need to spend €240 a night on mooring fees or their restaurant suggestion reduces evening meal prices by €10 per person, they soon add value – and have the language skills.

“Modern catamaran designs have opened charters up as an option for a much wider group of holidaymakers, rather than just being the preserve of sailors,” says James Foot at HELM.

Another trend noticed for several years “is an increasing demand for newer and larger, more comfortable yachts.”

A knowledgeable skipper can be worth their wage, which ranges from €190 to €200 a day, taking the stress of your yacht charter in Europe. Credit: www.helm.yt

Foot adds: “This could be driven by the new customer entrants, as well as the growth in clients from the United States. Because most Mediterranean marinas use stern-to mooring with lazy lines, the length of yacht isn’t really relevant from a space perspective, although it does obviously influence cost. I tend to prefer anchoring overnight, and with the price of marinas in Croatia at around €120 per night for a 13m yacht, we often advise clients to choose boats with a generator so they can enjoy peaceful evenings away from the hectic, sweltering marinas.”

Sunsail’s Katrina Lawson has noticed: “Some customers choose catamarans to help ease hesitant friends or family members onto the water, thanks to the extra space and stability the vessel offers, making longer trips more comfortable.”

When it comes to choosing monohull size, Katrina says vessel choice is usually determined by the sailing conditions, particularly in narrower channel passages.

Among the many online offerings for inland waterways, Mediamare Yacht Charter operates a fleet on the Baltic Sea, ‘located in the middle of the most beautiful sailing areas, protected by the offshore islands of Rügen and Usedom’.

Undiscovered Sailing offers bareboat and skippered sailing yacht holidays on Poland’s Masurian lake district, and Nicols organises river and canal motorboat fleets in the Hungarian inland waterways via local company Mahart, plus bases in France, Germany, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Ireland, which do not require the skipper to have boating qualifications.

Meanwhile, Locaboat offers self-drive canal boat hire that sleeps two to 12 people in Ireland, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and France.

A Nicols spokesperson said their charter holiday bookings were up 8% for 2025 holidays from last year.

He added: “In terms of destinations, the south of France is seeing the biggest growth as customers are seeking the sun. The three Nicols bases in this region benefit from fine weather all year round. The top three destinations in terms of growth on 2024 are: Canal du Midi, Camargue and Brittany. The top three destinations in terms of weeks booked per boat are: Camargue, Lot and the Netherlands.”

Keen charterers may be tempted to buy a yacht and hire it out when not in use, through a scheme such as Sunsail’s yacht ownership programme.

Benefits include being able to use equivalent sister ships or upgrade to larger models operated by Sunsail or The Moorings, up to 12 weeks of sailing a year and ‘zero operating costs’.

Corfu and the South Ionian have been knocked off the Greek charter top spots by the Cyclades and Dodecanese, says Nautilus Yachting business development manager Leanne Kifford, who believes sailors are seeking “lesser-known cruising areas which provide more challenging sailing conditions.

Both the Cyclades and the Dodecanese are known for stronger winds and longer sails between islands.” The areas retain authentic Greek island charm.

For the Cyclades, fly to Athens for a 40-minute transfer to Lavrion; for the Dodecanese, fly to Kos or Rhodes.

Exploring the Kisköre region of River Tisza with three children on a 13.5m motor cruiser – the largest boat on…

A skippered flotilla charter on the Dalmatian Coast is a dream come true for Laura Hodgetts, but can she really…

“How do you get from one lake to another?” My brother Jack, a ferry captain, wanted to know when I…

Planning on sailing in Europe? The Cruising Association shares its advice on what you need to know for a stress-free…

Want to read more articles like Yacht charter in Europe: where to sail?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter

Bob Shillito converts his classic 19ft (5.8m) clinker boat for near-silent river cruising

Just like many estuaries, here on the River Fowey in South Cornwall, it’s a peaceful haven for nature, but motoring along in a petrol or diesel-powered boat shatters the tranquillity and harms the environment, writes Bob Shillito.

Believing there is plenty of scope for converting existing boats to use quiet electric motors, even where there is little or no access to shore power, I set out to demonstrate that a professional-standard inboard motor conversion could be achieved at an affordable price for typical boat owners.

So I acquired the classic 19ft (5.8m) clinker-built river boat Swift for the conversion.

Built in 1962, she was originally fitted with a 2-stroke Stuart Turner petrol engine, which may have been state-of-the-art 60 or more years ago but is certainly not in the 2020s!

The original noisy Stuart Turner petrol engine. Engineering masterpiece or an industrial relic?

The engine still worked but was very noisy, smelly and emitted a lot of oil.

I had no qualms about removing the engine as the boat is hardly a museum piece, and Swift would probably have been destined for the bonfire without this new lease of life.

While marinas generally offer mains power and charging facilities, a river mooring is more challenging for an electric-powered boat.

While doing research, I kept being told that creating an electric-powered boat with no regular access to shore power was a non-starter, which was not what I wanted to hear!

Thus, the challenge was set.

Having launched Swift in late 2021 (and ensured that she’d float, which was not initially obvious), I set about establishing some real-world facts and fitted an ePropulsion Spirit 1.0 Plus to an outboard bracket.

This is a 1kW motor (roughly equivalent to a 3hp petrol outboard) with a 1.25kWh battery.

I wasn’t expecting it to be enough, but it turned out to be remarkably effective. I could cruise the Fowey River for an afternoon at half power at about 3.5 knots.

Launch day after a major refit is always tense. First trials for the new electric-powered boat. Credit: Bob Shillito

Top speed was about 4.2 knots, which was similar to the old Stuart Turner.

And, of course, the outboard was dragging the original prop through the water, too.

From this, I concluded that an inboard motor of about 4kW would be right, with at least 5kWh of batteries, giving a bit over an hour at full power but many hours at, say, 30%. The target range was set at 9 miles.

Clearly, the boat needs to beat the powerful spring tide currents on the river but it’s never going to exceed its hull speed of 5.9 knots.

With the existing 11/7 bronze propeller (ie 11in diameter, 7in pitch) and estimated prop slip of 35%, I reckoned the top speed (at 1,500rpm) would be 5.6 knots.

Following the trials, the design criteria were set at:

To meet the criteria, a balance needed to be struck when specifying the motor, batteries, solar array and mains charging.

Motor manufacturers or their distributors generally offer a complete package, and while that eliminates much of the technical risk and saves the owner from having to grapple with some of the technical factors, it can be an expensive route to take.

For example, one motor that seemed reasonably priced at first glance worked out at £18,000 when fully specified by the distributor.

Of course, there is always the hard-core route: get an old golf-cart or forklift motor and a retired Nissan Leaf or Tesla battery pack.

These can be broken down and rebuilt using custom electronics for a very reasonable cost but we’re talking about some seriously technical work, both mechanical and electrical.

I did consider this approach, but the objective is to go boating, not spend years in the workshop grappling with tech issues to achieve the ideal electric-powered boat.

Furthermore, I wanted to achieve a repeatable, quality result that did not look or feel home-spun.

Dozens of inboard electric motors are listed on the excellent plugboats.com website, but most are not available here in the UK.

Three that are readily available were considered in detail. The Lynch Yellowtail/Marlin, the Bell Marine Drivemaster and the Waterworld range.

Lining up the Waterworld motor to figure out engine mountings. Credit: Bob Shillito

I selected the Waterworld 4 from Energy Solutions for several reasons: it is a compact design with good control systems and a significantly lower price than the alternatives.

Waterworld also provides a very good manual, which helps ensure a trouble-free installation.

Indeed, the installation work was straightforward and completed in a couple of days, details are covered further down the article.

The engine connected to the original propshaft via a flexible coupler. Credit: Bob Shillito

The motor runs at a top speed of 1,500rpm, which matches the nominal speed of the engine it replaced, meaning that the original propeller and shaft could be retained.

You can power a boat with traditional lead-acid batteries or with lithium.

Lithium batteries are much lighter, can use their full charge, last longer (more charge-discharge cycles), but are much more expensive.

Either way, the 48V motor system would need several batteries in some combination.

A usable 5kWh of lead-acid batteries was going to work out at about 400Kg, which would overload the boat, so the decision was made.

But which lithium batteries? LiFePo4 is the preferred battery chemistry for this type of application, and there are a lot available.

Furthermore, all lithium batteries require a battery management system (BMS) to ensure they charge and discharge evenly and safely, which may be within the battery or external.

The Victron mains charger, which has actually had little use due to the success of the solar installation. Credit: Bob Shillito

You can’t get away from BMS: lithium batteries won’t charge properly without one, and the early lithium batteries that lacked them suffered from reliability issues.

Typically, the more expensive batteries have a data connection (called CanBus) which allows communication between them, the BMS and the motor’s controller to keep everything in balance.

We all know how electronics on boats can pack up at the slightest opportunity.

Some of the batteries have fans in the side, which didn’t seem like a great idea in a marine environment, either.

With all this in mind, I selected a reasonably priced battery with an internal BMS, the Polinovel Novel 12100 from Quality Source.

Four of these, connected in series, add up to 48V and a total store of 5.12kWh of energy.

A screen from the app used to monitor the status of each battery, and showing here the voltage, current draw and temperature when motoring. Credit: Bob Shillito

However, with no communication between the batteries, you need to keep an eye on their individual state-of-charge to ensure that they don’t drift out of sync, with one battery at a higher or lower charge than the others.

Fortunately, each battery has a Bluetooth link so you can use a phone app to monitor the state-of-charge, voltage and temperature.

The combined weight of the motor and batteries is a little less than that of the original 90kg petrol engine, with better weight distribution in the boat.

The batteries fit neatly under the V-berths in the cabin, two on each side.

Swift’s large cabin provided an ideal area for solar panels, although the curvature of the cabin top meant that flexible panels were needed.

Several types of panel were considered, with the objective of fitting the largest area possible.

One supplier, the Italian company Solbian, custom builds panels to your dimensions, which is attractive but costs around three times the price of standard panels.

Three 110W SunPower panels were chosen for their fit, price and flexibility.

My prior experience of solar charging was limited to bilge pump configurations, so I carried out charging trials to ensure the system worked correctly before gluing the panels to the boat.

Testing the solar array with the charge controller and batteries to ensure they all behaved as expected before they were installed. Credit: Bob Shillito

The solar array supplies up to 1.5kWh each day to the batteries through a Victron MPPT charge controller.

Victron is the market leader in this area, and this controller is a superb piece of kit: at under £200, it is fully configurable and has an excellent app that shows you where in the charge cycle it is operating, the maximum charge rate and the total for each day.

The solar charge system always remains on, meaning that the batteries can be charged while the boat is in use, thereby extending the range.

A Victron Titan mains charger was also selected and installed, which can fully recharge the battery array in under four hours when shore power is available.

Being an older design, the Titan’s controls are far less sophisticated than the solar unit but it does the job – which is just as well because there is very little choice when it comes to 48V chargers.

The boat has been in use for two months, and trials have shown not only that the design criteria were exceeded but that the revitalised Swift is a beauty to use.

The target cruising speed of 4 knots is achieved at a surprisingly low 1.2kW power consumption.

Because the original propeller is smaller than the recommended size, at maximum revs of 1,500rpm, only 2.8kW is used – rather less than the rated power of the motor.

This is good news, as it reduces current draw from the batteries and helps to extend the range while still achieving the maximum speed when needed, such as to beat the strong currents associated with spring tides in Cornwall.

Three screens from the app used to monitor the Victron solar charge controller showing (from left) the current charge status; settings; and a summary of the previous days’ charging performance

At around 18 nautical miles (33km), the range is at least double that of the original design criteria.

We have been able to make trips from the mooring, out to sea to a favourite beach and back – 8 miles – and been surprised to find that over 70% of the battery charge remains.

After a day or two, the batteries are fully recharged, and, outside of testing, pontoon charging has not been needed.

The lack of noise is an extraordinary experience: at the helm, it’s perfectly possible to carry on a normal conversation with someone sitting on the bow.

Bob is now experiencing near-silent cruising on his electric-powered boat. Credit: Bib Shillito

When cruising the backwaters, wildlife no longer flees, and other water users are intrigued: people are amazed at how silent the boat is, particularly when manoeuvring at a jetty or pontoon.

Gone forever is the lingering oily smell in the cabin that some find an acceptable part of boating and others – my wife included – definitely do not.

An electric conversion can be expensive. Sophisticated systems and lithium batteries increase the price.

However, careful selection of components brought the total cost in at a similar price to a professionally-installed diesel engine, under £8,000 all in.

Swift is now set for a new lease of life, and hopefully, others can learn from the conversion.

The installation of the electric system was remarkably straightforward in contrast to the renovation of the boat, which took months.

Since this is an article about electric boating and not clinker boat restoration, I’ll gloss over the eight weeks spent cutting in new pieces of plank and rib, and scraping greasy, flaking paint out of the bilges.

The Waterworld motor has mounting brackets designed to adapt to most situations: they can be used either way up via various sets of bolt holes.

In most cases, where there are conventional longitudinal engine bearers in the boat, it would be simple to fit anti-vibration mountings (sold separately) and then bolt the engine to them.

However, Swift has two hefty cross beams to which the old Stuart Turner was attached, which made mounting difficult since they were in the way

of the bolts.

The rear of the graphic display and the solar charge controller; data cables and wiring are above, power cables and isolator are below. Credit: Bob Shillito

Once these issues were overcome and the engine was in, the motor was aligned to a new flexible coupling attached to the original ¾in bronze prop shaft.

The four 12V, 100Ah lithium batteries are not much bigger than regular car batteries and can be installed anywhere fairly close to the motor, to minimise cable runs and lost power.

As the boat was a little stern-heavy with the old motor, I wanted to set the batteries forward.

As luck would have it, they fit perfectly under the V-berths in the cabin, two on each side, where they are secured with rack-straps.

A benefit of lithium batteries is that they do not need to be fitted upright, so I could lay them against the hull on pieces of Correx floor protection sheet.

As the cables had to pass through the bilge from one V-berth to the other, I ran them through lengths of plastic piping for additional protection.

The solar panels were stuck to the painted cabin roof with CT1 adhesive, while the cables pass through the roof and are sealed in place.

Parts of the installation showing the throttle, graphic display, ignition key, main relay and the motor. Plus a fire extinguisher. Credit: Bob Shillito

Through-deck cable glands would be a more robust solution, but at a higher price.

The motor comes with a wiring loom for all controls and a master relay. This is very simple to wire up – just a matter of ensuring the cable runs are not too long before cutting holes for the throttle control, display and ignition key.

Power cables need to be made up to connect the motor to the batteries via a master fuse, isolator switch and bus bar. All these marine-grade items can be bought from a supplier such as 12 Volt Planet, along with terminals, insulator caps, and tools.

The 35mm2 power cables are substantial and need perfect termination to avoid problems, so a proper crimping tool is essential.

It is worth practising some crimps on short lengths of cable first.

Swift’s solar array, glued to the cabin roof. Credit: Bob Shillito

The chargers were simply mounted in convenient locations where they are most protected from damp and any rainwater leaks.

The mains charger is fed by a standard marine/outdoor 16A cable inlet, to which a cable can be fitted when using shore power.

Being a wooden boat, a reliable bilge pump is vital, so I decided to keep it separate from the motor installation.

I retained the existing configuration, installed a year earlier, of an automatic pump, small 12V car battery, 10W solar panel and charge controller.

You can watch Bob’s video about the conversion by clicking here.

Cost of conversion to an electric-powered boat

Norman Rubenis gets ‘Thunderstruck’ when he ditches the diesel and converts his Contessa 32 to run on a 10kW electric

Rupert Holmes takes an in-depth look at the practicalities and pitfalls of choosing electric propulsion, or even an all-electric boat

Felix Marks attempts to embrace a green future for his Tofinou 7, but his experiment with an electric motor proves…

Dena Hankins is on a global voyage aboard her 1984 9m Baba 30 converted to run with an electric propulsion…

Want to read more practical articles, like Electric-powered boat for under £8,000?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter

With a few practical woodworking skills anyone should be able to replace a plank on a carvel-built wooden hull, as Richard Johnstone-Bryden discovers

One of the beauties of a traditionally planked wooden boat is that each individual hull plank can be replaced if they lose integrity through rot, old age or accident, writes Richard Johnstone-Bryden.

The procedure should not be beyond the skills of most practical boat owners.

Here, Harry Morgan removes an old hull plank before cutting and fitting a replacement.

1. With filler picked away from the nail head and the copper rove ground off inside the hull, Harry uses a centre punch to drive the nail back through the hull plank so it can be extracted with a claw hammer.

A metal dolly held against the outside of the hull counteracts the vibration.

2. With the damaged wood cut away, the adjoining end of the sound plank also needs to be pulled away from the timbers.

3. The length of this adjoining plank is then marked up to ensure that the scarf joint will be over a timber to provide additional strength.

4. A wedge keeps the still-attached plank steady and away from the hull while Harry cuts it to length. He’s using a Japanese kataba saw, but a tenon saw will work too.

5. A smoothing plane removes the bulk of the wood required to form the inboard half of the aft scarf joint.

6. Harry now saws a straight edge at the aft end of the scarf. The idea is to create a bull-nosed edge to the outer part of the joint rather than a difficult-to-fasten feather edge. He cuts the rest of the joining surface away with a bull-nosed plane

7. A similar scarf needs to be cut on the inboard end of the forward plank. Again the plank is wedged out for stability, though Harry is using a smaller block plane because of the restricted working space between the inner face of the plank and the hull.

8. To determine the exact shape of the new plank, Harry nailed on a temporary spiling plank. He uses a dummy stick placed against the existing upper and lower planks to draw lines on the spiling plank – these will be transferred back to the new plank to determine its exact width and length.

9. The positions of the timbers are also marked on to the spiling plank and each timber is numbered so the plank can be pre-drilled for fastening later.

10. An alternative to a dummy stick is to use a set of dividers to measure the required width at each numbered frame. These measurements are then plotted out onto the replacement plank.

11. Using the spiling plank, Harry now plots the positions of the frames onto an overwidth 3⁄4in-thick larch plank.

12. Harry places the inboard edge of the dummy stick along the line on the spiling plank and runs a pencil along the outer edge to plot one edge of the replacement plank. He does the same for the other edge.

13. The plank can now be cut – slightly oversized – with a handheld circular saw, which gives a good, clean line.

14. A plane finishes off the edges to make the plank the exact width. After that it is run through a thicknessing machine so it exactly matches the thickness of the boat’s existing planks.

15. Scarf joints are cut on the ends of the new plank, and the edges are accurately trimmed to mate with those on the boat.

16. The moment of truth! The time spent marking up and accurately cutting the joint has paid off, as the two halves of the forward scarf fit together perfectly. This joint will then be glued and allowed to cure.

17. Having secured the forward scarf joint, wooden battens are used to clamp the plank in position along the hull so it can be permanently fixed with copper nails and roves.

18. Where the plank forms part of a sharp curve in the hull, a bridging batten is used: wedges are hammered beneath the bridge to force the plank into position.

The plank and timbers are then joined using copper nails and proves to complete the repair – (above) being demonstrated on a different job.

Boatbuilder and finisher Lyndon March explains which types of wood work best for different repairs and modifications on board

Kit boat builder Polly Robinson shares her tips for painting and varnishing a plywood-epoxy boat

Face up to the task of applying veneer with the help of boatbuilder Tony Davies

Zoran Glozinic saves some cash by making a new cockpit grate for his yacht using redundant old wooden kitchen shelves

Want to read more practical articles?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter

A range of boats, from the Saxdor 340 to the Bavaria SR35 HT, will be making their UK debut at the 2025 British Motor Yacht Show

The 2025 British Motor Yacht Show will feature UK debuts when it opens next month.

The four-day show at Swanwick Marina in Hampshire is an appointment-only event, allowing boat buyers to meet brokers and find out more about new boats for sale.

Argo Yachting will present the UK debut of the Saxdor 340 GTWA – a wheelhouse walkaround model with large side terraces and glass sliding doors and roof, allowing plenty of natural light in the cabin.

Sunseeker’s Predator 55 will be unveiled for the first time in the UK at the show

Other UK debuts include Sunseeker’s all-new Manhattan 68 (2025) and Sunseeker Predator 55, the Axopar 29 CCX, Bavaria SR35 HT and SR38 HT, Fjord 39XP, Virtue V10 Cabin

These join the previously announced Bellini Astor 36 and Pearl 63.

Other models on display include:

Sunseeker:

Fairline:

Princess:

Salorenzo Yachts UK:

Exhibitor Approved Boats will also debut Absolute Yachts.

Shoreside, marine decking specialists Aquadeck and Permateek will be exhibiting alongside Nautafix Global and Meridien Modena Ferrari.

The Bellini Astor 36

Graham Bristowe, general manager of Premier Marinas Swanwick, commented: “The British Motor Yacht Show continues to set the standard as the UK’s premier event for serious buyers of luxury motor yachts. With a record number of UK debuts, exclusive showcases from industry giants and a relevant selection of premium brands ashore, the 2025 show promises to be our most spectacular yet.

“We look forward to welcoming guests to Premier’s Swanwick Marina for an unparalleled showcase of design, craftsmanship and innovation,” he added.

The 2025 British Motor Yacht Show will take place from 15-18 May 2025.

To book an appointment visit: BritishMotorYachtShow.com

Just like today’s sailing cruisers, the new generation of motorboats give you a lot of space for their length. David…

Gilbert Park undertakes some training for riding out heavy seas and wind in his Mitchell 28 – but first has…

Many moons ago I had a premonition that Hunter Boats ought to build a classy little motorboat for customers who…

Retired doctor and practical motorboat owner Gilbert Park has undertaken numerous DIY challenges on board his various motorboats, publishing several…

Want to read more articles?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter

Stu Davies explains how he fitted a new cam belt to the diesel engine in his 1999 Beneteau 381

Venerable is a word to describe the Volvo Penta MD22 engine fitted to my 1999 Beneteau 381.

The 50hp MD22 is a marinised version of the Perkins Prima 50, which was also used by British Leyland as the diesel engine for their Montego and Maestro 2.0 saloons.

It was developed jointly by British Leyland and Perkins back in the 1980s. Volvo Penta also offered a turbocharged version of this engine, the TMD22, producing 78hp.

This engine is basically the same as the MD22 with the addition of a turbocharger and extra heat exchangers and coolers.

Some of the earlier ones have a different fresh water intercooler system, but essentially, the basic engine is the same.

It’s important to check your cam belt every year to ensure the tension is correct. Credit: Stu Davies

The engine is a single overhead cam engine with the cam being driven by a cam belt, a simple method of valve operation BUT having the possibility of dire consequences if the cam belt breaks!

I’m sure most motorists are aware of the costs that can be incurred if the belt breaks and the pistons contact the valves.

The purpose of this article? I wrote the job up quite a few years ago for PBO when I first had the boat and have since changed the cam belt several times.

Some of the information I sourced all those years ago has now changed, so I wanted to update readers and reveal how the engine and belt have fared over the years.

After conducting some more research, I found that the MD22 and its variants have a relatively low compression ratio but are not ‘free wheeling’ engines (ie there is not enough room for the pistons to miss the valves if the belt breaks).

Normally, when the belt breaks on these engines, the valve hits a vertically opened valve, which is driven directly by the cam shaft and snaps the cam.

Cams for this engine are now nearly impossible to source so checking and changing the cam belt, if necessary, is important.

As I was a maintenance engineer, I’ve always done my own engine work so changing the cam belt is just a routine job for me!

On the subject of the cam belt, Volvo recommends that owners ‘check for cracks and oil contamination’ and ‘change if necessary’.

Personally, I find this is not very helpful if you don’t have the expertise to make a considered judgment on what is good or bad or necessary.

If, like me, you were brought up to ‘change cam belts religiously’, this information seems a bit haphazard, although after further research I discovered that because the belt is 30mm wide it would last longer than a normal, thinner one found on modern vehicles.

More data has since become available, and Volvo Penta now recommends changing the belt every three years.

I did some checking in my logbook and found out that I last changed the belt in 2014, and have only put 400 hours on the engine.

Anecdotal evidence shows the average boater puts around 100 hours a year on the boat’s engine.

I will say in my defence that I religiously check the belt’s condition every year.

The engine on Sacha, my Beneteau 381, is now 25 years old but is still going strong; I change oil and filters regularly, and I changed the injector nozzles a few years ago, which made a massive difference to the sound and smoothness of the engine.

Accessing the engine is a relatively simple task on a Beneteau: lift the companionway steps, and the front of the engine is easily accessible.

The top of the cam belt cover has an inspection piece which is easily removed to expose part of the cam belt for checks.

Locate the hole in the cam cover for the locking pin. Credit: Stu Davies

Volvo Penta recommends making a chalk mark on the belt and then manually turning the engine over, inspecting the belt for cracks and oil contamination until the chalk mark appears again.

A word of warning here: I tie off the manual stop lever on the injector pump to make sure the engine doesn’t start while barring it over!

Before starting the job I collect the tools and parts needed.

Basic hand tools, spanners and sockets, an 8mm Allen key plus the ‘pins’ to hold the crankshaft, camshaft and injector pump in their relative positions whilst changing the belt.

I used 6mm threaded bolts and some 6mm bar to make these pins up.

Finding a new cam belt is becoming more difficult. The one for Stu’s engine also fits the old Maestro and Montego cars

New cam belts are getting harder to find nowadays – unlike a few years ago when I could source a new belt for a 2-litre diesel Montego from my local car parts supplier.

Today, one of the best sources is www.parts4engines.com – and this is where I bought my cam belt, which arrived marked for a Montego engine by the manufacturer, Gates.

Changing a cam belt involves placing the engine in a position and locking it there so the timing of the injector pump and cam shaft isn’t lost.

I started the job by locating the locking flywheel pinhole on the starboard side of the engine under the inlet manifold.

This is a 6mm hole in the flywheel housing that corresponds with a similar hole in the flywheel.

Make sure you insert the flywheel locking pin to lock the engine into position. Credit: Stu Davies

I then located the cam shaft locking pin hole; this 6mm hole is accessed by removing a 6mm screw at the top front of the cam cover.

I turned the engine over with a 24mm spanner until my wife, Laura, was able to push a 6mm bolt through the flywheel hole, and I could drop a 6mm pin into the cam locking hole and, similarly, with the cam shaft.

The engine was now locked in position so the cam belt could be removed and replaced.

The next job is to remove the fresh water pump pulley so the cam belt cover can be removed.

Four 8mm-headed bolts hold it on. The bolts were first slackened (it is best to do this first so the pulley is held by the alternator belt to stop it from turning), and then the alternator holding bolts were slackened so the cam belt could come off.

The fresh water pump pulley needs to be removed to access the cam belt cover. Credit: Stu Davies

The water pump pulley is then removed. The clips around the edge of the cam belt housing are easy to flip off, and the cover can then be removed.

A little bit of wriggling is required, but this will expose the cam belt drive train. The injector pump drive gear can be seen.

Remove the cam belt drive train cover by undoing the clips. Credit: Stu Davies

You need to fit two 6mm bolts through the non-threaded holes in the pump drive wheel – this locks the injector pump in position.

Now that the engine is locked into position, the belt can be safely removed.

The four 10mm bolts which hold the cam wheel are then slackened slightly; the holes are elongated to allow a little bit of wriggle room when fitting and tensioning the new belt.

Use two 6mm bolts to lock the injector pump into position. Credit: Stu Davies

The next job is to slacken the belt tensioner using an 8mm Allen key before the jockey wheel can be removed using a 13mm socket on the holding bolt.

This will give enough room to manoeuvre the belt around the bottom pulley.

Then the tensioner pulley can be removed to give some more room.

Now, the old belt can be removed and compared with the new one.

It’s important to note the direction of the rotation arrows (the engine rotates clockwise looking from the front).

After examining my 10-year-old cam belt, I found it was in perfect condition with no sign of cracking or excessive wear.

Thoroughly check the cam belt for signs of cracking or wear. Credit: Stu Davies

The jockey wheel and belt tensioner pulley wheel bearings were also checked for wear.

They were in perfect condition with no noise, and the seals were in excellent condition. Some people would change these too as a matter of course.

The case covers can be cleaned up, getting rid of alternator and cam belt dust, and the new belt offered up to the bottom pulley, cam wheel and injector pump pulley.

There are arrows on the new belt indicating which way to fit it.

Move the jockey wheel into position and make sure the bolt is loosely fitted. It is worth noting that the stiffness of the new belt makes it slightly difficult to hold the pulley in position while fitting the bolt.

Removing the jockey wheel will give you more room to manoeuvre the belt around the bottom pulley. Credit: Stu Davies

The belt tensioner pulley is then fitted loosely.

The slacking of the cam shaft pulley securing bolts is handy here, allowing a bit of wiggle room to get the belt teeth properly lined up.

There is an Allen keyhole in the pulley base which can be used to tighten the belt with an 8mm Allen key.

The elongated holes in the cam wheel fixing will ensure that as the belt is tightened, the cam wheel moves slightly, but the cam remains still.

The belt tensioner pulley. Credit: Stu Davies

Many manuals suggest using a special tool to check the belt tension.

As a veteran of many cam belt changes, I’m confident of my ability to check the tension of the belt by feel.

This is the third time I’ve changed the belt and, touch wood, all has been well.

Use an 8mm Allen key to tighten the cam belt tensioner pulley. Credit: Stu Davies

I aim for a 1cm deflection and no ‘twanging’ when the belt is flicked.

The belt is driven via the teeth, unlike a V belt, which relies on tightness to make it grip.

The rest of the job is a straightforward replacement of the case, water pump pulley and alternator belt.

Stu Davies shows you how to check and replace an engine’s raw water pump impeller, and explains why it’s an…

Engineer Stu Davies explains the steps you should take to make sure your boat’s engine is protected over the winter…

Stu Davies shares useful maintenance tips on how to keep your 2-stroke and 4-stroke outboard motors running sweetly

Every boat owner should know some basic engine maintenance. Stu Davies shares how to tension the alternator drive belt

Want to read more practical articles?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter

The crinkle of crisp boilersuits shuffling around the boatyard heralds a new season

Every year, just as the Essex marshes begin to sprout with the first buds of succulent samphire, a final, final demand to pay the TV licence wafts through my letter box and lands on top of the others.

These are as sure signs of spring as the knock on the door a few seconds later.

“Oi,” says the gruff, familiar voice through the letter box, “pay your TV licence then get your backside down the boatyard and get your boat cover off.”

The truth is that Adi knows too well that his berth holders, and me in particular, are an indolent bunch of slackers who need rousing from the cosy months of hearth-side hibernation when we’d happily forgotten we owned boats.

Down in the yard, those with delusions of adequacy are shuffling around in a confused daze like meerkats in brown and blue boilersuits, and there’s even one wearing crisply ironed white overalls with epaulettes, which denote senior rank and an altogether higher degree of competence.

Most of us, though, are realists, assured above all that if we do anything, as Adi often intones wearily, that we’ll either damage our boats and land him with a load of work or damage ourselves and land him with a load of work.

He’s got a point, and to that end the yard has withdrawn its supply of yard ladders after someone in white overalls fell off one and sued the yard and the neighbouring boat owner who’d left an open can of red antifouling at the bottom of the ladder.

When his overalls were put through the wash and they came out pink he sued his wife and she left him.

Like all health and safety initiatives, the ladder edict led to unintended consequences, as more resourceful boat owners made their own and the most resourceful ‘borrowed’ them.

In another case, the fall from Grace, which was the name of the boat, was cushioned by landing in a paint tray of antifouling, which after washing turned the brown overalls mauve.

The one intended consequence of the seasonal mayhem is that the chandlery at the top of the yard has stopped its 20% off sale of ladders, antifouling and overalls and is doing a roaring trade.

The other consequence is that berth holders have stopped trying to self-harm with angle-grinders and orbital sanders and wot not and, like young buck kangaroos, are trying to harm each other and punch each others’ lights out.

At least, they would have done, but for the fact that there’s not enough space in the yard to swing a cat or even a sharp, right upper cut.

All the plastic boats, many of which have summer berths downriver, are on the hard waiting for their lift in, and all the wooden boats are in their mud berths waiting for their annual lift out.

It’s like a game of chess with as many pieces as there are squares on the board.

Being naturally of a defeatist nature I turned to walk the few yards home but somehow discovered inner backbone and renewed motivation thanks to Adi, who blocked my path and kindly growled: “Oh no you don’t, Dave, get your covers off and get varnishing.”

I walked along the pontoon and started to peel back the winter cover which, to my surprise, was far better secured than I remembered with proper knots of the type you find in books.

I was even more surprised when a voice on board said: “Oi, get off of my boat.”

This puzzled me for a bit as I hadn’t remembered selling it, but then was helpfully informed they’d shuffled the berths around in the winter.

I found Snipe, my 1953 wooden Blackwater sloop, and with trepidation approaching terror peeled back the cover like a mourning shroud, to see what state of shameful dereliction she was in.

And it was worse than I thought.

In a panic, I lifted the floorboards and looked in the bilges.

I then examined the lockers, shelves, forepeak and galley where all I found was a half-eaten pack of mouldy ginger nut biscuits.

With remorse, regret, shock and shame, I trundled to the chandlery, cursing myself.

I’d made the stupidest of beginner’s errors, and it was going to cost me dearly.

There were no tea bags on board!

Want to read more articles?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter

After struggling with a heavy lifting keel, Brian Johnson builds a simple tackle to make light of the problem

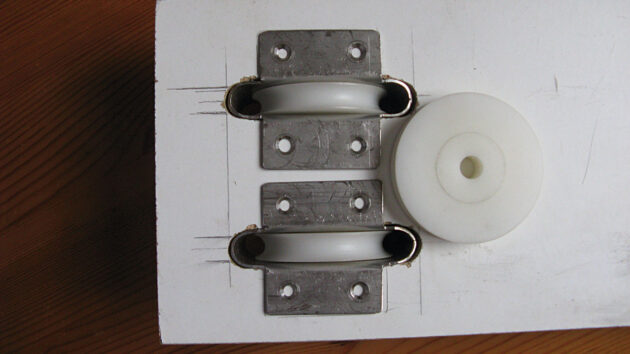

I was asked by a friend to make some fittings for his new boat, a Parker Super Seal, to make it easier to lift the lifting keel.

The existing arrangement was a single sheave, mounted in the top of a box which fitted over the keel slot.

A rope tied to the top of the keel passed over this sheave and was led aft to the halyard winch.

Another Super Seal-owning club member had improved on the standard system by fitting a box sheave in the keel.

An anchor plate fitted on the port side of the keel slot raised the lifting tope about 100mm above the deck.

A similarly raised block on the starboard side allowed the rope to be led from the anchor point through the keel block and the starboard block to a deck organiser, then aft to a winch, thus giving a 2:1 advantage and halving the effort needed to lift the keel.

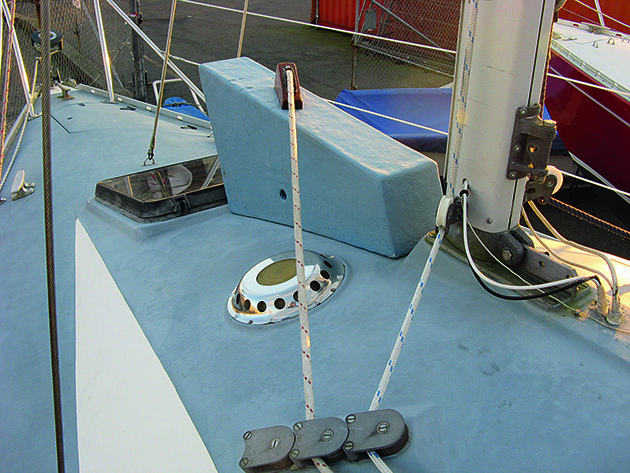

The fully raised lifting keel showing the lifting sheaves and locking pin

It was necessary to raise the anchor point and starboard block because the keel projects from the keel slot when fully raised.

It also helped to lift the rope clear of a deck vent.

We decided instead to fit two sheaves in the keel and blocks on both sides of the keel slot, one of which would incorporate a strong point to fasten the end of the lifting line.

This would give a 4:1 advantage, or a quarter of the effort needed to lift the keel.

We first removed the lifting keel from the boat, measured its thickness at the point where the sheaves were to be fitted, and machined them from nylon such that the diameter at the bottom of the groove was 5mm greater than the keel thickness,

This ensures that the lifting line will not chafe on the edges of the slots in the keel or on the sheave boxes.

The sheaves will accept 10mm diameter rope, and the centres are drilled to take a 10mm pin.

We also made two slightly smaller sheaves for the deck fittings.

I used thin card to make a template of the keel sheave boxes, the sides of which were designed to be slightly narrower than the lifting keel.

Keel sheaves in jig with a loose sheave to give the slot spacing

Once I was happy with the shape and size of the mock-up, I cut two pieces – one for each sheave -from 1.5mm stainless steel using an angle grinder.

I filed the edges smooth, then bent the pieces to shape around a suitable diameter bar, the join meeting in the centre of one end.

I bent the flanges over with the pieces held in a vice, using a hardwood spacer to prevent the box from being squashed.

When satisfied with the bending and sure that the sheave would fit, I marked and drilled the boxes for the sheave axle pins and for the screws to secure them into the keel – the latter holes being countersunk for the screws.

I cut the axle pins from 10mm diameter stainless steel rod, approximately 4mm longer than the overall thickness of the sheacces.

I faced and drilled the ends with an 8mm drill to a depth of about 2mm – this left a rim of only 1mm, which was easier to rivet over when the sheave and box were put together.

The port side in-line raise sheave

Drilling the end of the pins in this way also helps to avoid riveting too tightly, which could jam the sheave.

When it came to the two fixed blocks that sit over the edges of the keel slot, the port side block was fairly straightforward, with the support bracket set in line with the keel slot and the sheave offset slightly to overhang the slot.

The keel itself is quite a bit thinner than the slot – nylon guide blocks keep it centred – which means there is plenty of clearance for the sheave and lifting line.

The starboard fitting was more complex, however, the sheave needing to both overhang the slot and be angled to lead the lifting line to the turning block.

The raised starboard sheave with knot around the anchor point

It also needed a strong point to anchor the rope, positioned so that both ends of the lifting line would run parallel to and from the sheaves in the keel.

The spacing between the sheaves in the keel was set by the size of the sheave in the port block.

I made more templates to get the correct angle for the base plates and to work out the lead angle from the starboard block to the organiser, forward of the winch.

I also used cardboard to refine the shape of the various parts before fabricating them from stainless steel.

For ease of access, most holes were drilled and, where necessary, countersunk before I welded all the pieces together.

Once all of the main parts were made and welded, I added a U-shaped anchor point and guides.

The guides are there to ensure the rope stays on the sheaves and also offers some protection against knocks.

The next task was to make a drilling jib to enable accurate positioning of the slots in the keel for the two sheave boxes, square to the sides of the keel and parallel to each other.

I marked the positions central to the width of the keel and around 30cm from the top to ensure the keel could be fully lifted and to allow the insertion of a locking pin.

I was apprehensive about drilling as I had been told that the keel had a steel or iron core, but fortunately, the area where the slots were to go proved to be a laminate consisting of an 8mm outer skin of GRP, the layers of plywood and filler.

A 17mm HSS drill bit coped easily, so I drilled the hole at each end of the slot and then removed the rest with a long-bladed jigsaw and a coarse file.

The next step was to liberally coat inside the slot with two-part epoxy paint to stop water from getting in to the keel laminates, and once it was dry the keel blocks were inserted, secured with stainless steel screws and any gaps filled with marine filler.

We returned the keel to the boat and hoisted it aboard using a jib halyard and lots of helpers.

I’d decided that, even though I had worked out where the fitting were to be located at the top of the slot, it was best to have the keel in place first to be sure everything would line up as expected.

It was fortunate I did because, in my reckonings, I had not taken sufficient account of the angle of the keel.

Because the keel tilts aft and does not therefore rise vertically, both of the blocks needed to be about 8mm further forward than I had calculated.

Once I was happy with the positions of the fittings, I marked the deck and drilled it to take 14-gauge self-tapping screws,

With the fittings bedded on marine sealant and screwed down, I threaded the lifting rope through the sheaves to test the system.

From its anchor point on the starboard fitting, the rope is led down through the aft sheave in the keel, up and over the raised block on the port side of the keel slot, back down to the forward sheave in the keel and finally up and over the starboard block and aft through the organiser to the winch.

With this system, the keel can be lifted quite easily even without the use of the winch, the weight being comfortably held by a halyard clutch and then a locking pin when in its mooring.

Three stages in the evolution of a Super Seal lifting keel mechanism

1. The original keel cover box with one sheave and no mechanical advantage

The system designed by Super Seal club member Mike Haise gives a 2:1 advantage

My modification looks similar, but actually gives a 4:1 advantage

Ben Lowings talks to Bjorn Haraldsson about his simple air-regulated keel

Galvanic corrosion is often something mainly associated with metal fittings on larger craft: however, David Parker has a cautionary tale…

Peter Poland looks at the history of keel design and how the different types affect performance

In our Maxi 84 boat survey, Ben Sutcliffe-Davies concluded that the antifouling needed to come off and whilst the keel…

Want to read more practical articles?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter

Bob Goode improves his Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 32’s sail handling by replacing the original fixed wire split backstay

My 2002 Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 32 was quite a simply-rigged boat when new: to keep the price reasonable, the builders had hardly pushed the boat out when it came to deck gear, writes Bob Goode.

The downside to this was that she could be a bit of a handful in winds above 20 knots, particularly if conditions were gusty. The solution was simple: improve the sail handling controls and fit better sails.

The original ‘Technique Voile’ sails were adequate but lacked the material quality to last long and quickly lost their shape.

One item that needed attending to immediately was the backstay.

The original, a 4mm fixed wire split backstay, did not allow adjustment to flatten the main and tighten the forestay in stronger winds.

I started by fitting a simple strop between the split stays: this allowed me to apply some tension, albeit not easily, to see if the results would be worth the expense and effort.

Bob checked the rig tensions with a good-quality tension gauge before starting work on fitting the adjustable backstay. Credit: Bob Goode

A positive outcome saw me dashing off to buy a good rig tension gauge and setting about recording the tensions in the rig.

Some research on breaking strains and comparison with the recorded tensions allowed me to design a simple cascade that would replace the existing split wires.

I used the strength of the existing wire backstay as a guide to the required strength in the replacement components to avoid introducing any weakness in the rig.

I would keep the same main section of backstay from the masthead but replace the 4mm 1×19 split wires with a single, 5mm 7×19 wire, passing it over a wire block fitted to the main part of the retained backstay.

The ladder was secured on a very calm day in a marina at low water – so no wash from passers-by to allow for fixing the check-line on the backstay. Credit: Bob Goode

The single wire would be shorter to allow for the adjusting pulley system.

Fitting would pose a problem as the mast would have to remain in place while the work was carried out.

Fortunately, the Sun Odyssey 32 has sharply swept back spreaders, so even with the backstay released, the mast should remain fairly secure.

I fitted a stepladder across the cockpit and roped it tightly in place.

Luckily, my berth at Chichester Marina is very calm, and at low water springs, the access channel is so shallow that there are virtually no moving vessels to create an unsettling wash.

Backstay secured and the Barton wire block in place with 7×19 wire threaded. The green line is a temporary check line to hold the backstay in place. Credit: Bob Goode

The stepladder allowed me to reach the connection where the original split wire was fixed to the single backstay running up to the

masthead.

To be on the safe side, I attached a temporary securing line and tensioned it to ensure the fitting at the masthead stayed in place.

With the new flexible wire already threaded through the wire block, I secured the new block to the existing backstay fitting and then connected the fittings back at deck level before threading the Dyneema rope.

Stopper knot and bobble which prevents the tension from being inadvertently released from the adjustable backstay. Credit: Bob Goode

I then used the original rig tension measurements to adjust the new backstay so that the rig was correctly tensioned again.

Next, I checked that the tension in the cap shrouds did not drop too far when tension was hauled on the backstay: this is important as the cap shrouds act partly as backstays and partly to keep the mast from inverting.

All that remained was to whip the knots in place and add a stopper to the adjustment line so that the backstay could not be inadvertently completely released.

Improved performance during the first sail in a fresh breeze quickly convinced me my work to fit an adjustable backstay was worth the effort.

And on top of that, I now have an extra line to play with on longer sails!

At each stage of the cascade, the safe working load (SWL) can reduce as the total load is shared between the parts of the subsequent cascade.

One end of the flexible 7×19 wire split backstay is secured to the existing deck fitting on the starboard side of the yacht.

From there it goes over a Barton wire block on the end of the existing backstay. The port side end of the 7×19 wire is fitted with a single 60mm block.

An 8mm Dyneema line leads from the port deck fitting over this block to a 50mm triple block.

With another triple block and jammer secured to the deck fitting, a 6mm Dyneema line completes the cascade.

Stainless steel wire

Assuming you don’t have exotic rigging, your mast is probably held up with 1×19 stainless steel wire – ie the wire consists of 19 single strands.

This construction is strong, with little stretch; however, it is also inflexible. If the wire is to go around a pulley, then the wire of choice is 7×19, meaning the wire is made up of seven strands, each consisting of 19 smaller strands.

This is not quite as strong as 1×19, but it is very flexible.

Typically, the breaking strain of 4mm 1×19 stainless steel is around 1,400kg, which is about that of 5mm 7×19 stainless steel.

A safe working load would be no more than half this figure.

Dyneema rope

Dyneema was chosen for its great strength, low stretch and minimal creep under load.

A typical 8mm line has a breaking strain of around 3,000kg, so it is over strength for this application.

The 6mm Dyneema has a breaking strain of around 1,600kg so is also over strength, but is much nicer to handle than a thinner

line would be.

Wire blocks

The breaking load of the Barton wire block is 1,300kg: 60mm Lewmar Synchro blocks are specified to have a safe working load of 800kg, and the 50mm ones around 450kg.

Correct rig tension will maximise the efficiency of your boat’s sails as well as reduce stresses on the mast. David…

The ability to sail faster and more efficiently can also be safer and more satisfying. Peter K Poland explains...

Sailing efficiently when the wind comes astern doesn’t mean you have to fly a spinnaker or cruising chute. David Harding…

Some boats need persuasion to make to windward, so tweaking the sails to best advantage can make all the difference.…

Want to read more practical articles like How to fit an adjustable backstay?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter

Roger Cottle was presumed dead after falling overboard a 27ft yacht and lost at sea for five-and-a-half hours in a holed lifejacket, at night

Falling overboard, I discovered that what they don’t tell you on the sailing courses is that a safety harness is great until you fall in, and then you become a waterskier.

I was dragged across the waves and then under the bottom of the boat for about half a minute, where I hit my head on the propeller.

Then the stanchion eye, which I had clipped onto, was ripped from the boat.

It was quite a lightweight 27ft yacht, and the weight of me in all my sailing gear being dragged through the water, pulled

it clean out.

I ended up swimming in the Atlantic with the metal weight between my legs. I released it and kicked it off, along with my boots, and watched the boat sail away.

A chart showing where Roger fell overboard and where he was rescued

My crewmate, Paul, was chucked out of his bunk and realised we were in trouble because the boat was full of water.

He came up on deck, saw I wasn’t there and the stanchion eye was missing and set off an emergency position indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) alert.

The newspapers all reported at the time that I had been wearing an EPIRB, but 18 years ago, personal locator beacons didn’t exist; I just had a lifejacket with a hole in it.

The little light had been ripped off, I had to keep blowing air into the hole to keep the lifejacket inflated.

Paul also let off a distress flare and turned the yacht back. He came close to picking me up but couldn’t quite manage it.